Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

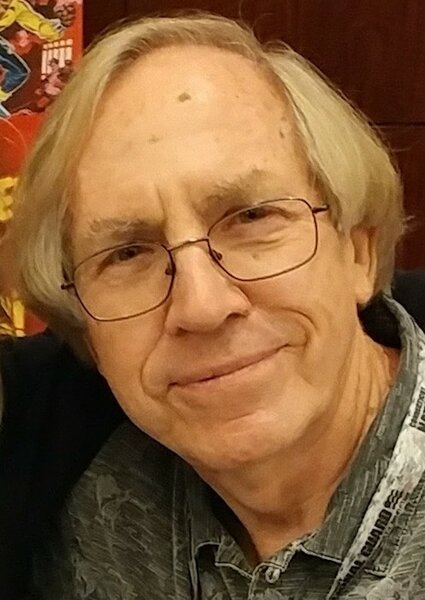

Comics legend Roy Thomas on Marvel's The Vision and working with Stan Lee

The comics industry wouldn't be the same without Roy Thomas.

The toughest part about interviewing Roy Thomas is what not to ask him about.

Thomas' career spans such a large swath of comics history, it would take multiple interviews to cover even half of his legacy's high points. And he's not even close to being done.

It was recently announced he was doing a two-part X-Men: Legends story set during his groundbreaking tenure on the book, when he was a pivotal figure during a creative highpoint for comics called the Bronze Age. Born in 1940, Thomas got an early start reading comics (he believes the first comic he laid eyes on was 1945's Green Lantern #16 with a cover by Paul Reinman). Since then, Thomas has been around for most of the lifespan of the American comic book industry.

"Just by sheer luck and my personality or whatever is, I've been around for the whole ride," Thomas says. "But the interesting thing is that, for whatever reason, I never stopped reading comics. Comics kind of left me because for a time, superheroes sort of just went away."

But they came back to him in a big way "one day before July 4th, 1956, I walked in my local drugstore to buy some fireworks, and here's Showcase #4, with the Silver Age Flash, staring at me," he says. It's that type of recall and genuine affection for the medium that made him a comics fan for life, and part of the first generation of comics fans to grow up and work in the industry they love. That fandom still informs his current work, overseeing the long-running comics fanzine Alter-Ego. Each issue is a mini-history lesson on comics, because who better to teach readers about comics history than someone who's been around and involved in the creation of so much of it?

Few creators can match Thomas’ list of credits. He has scripted just about every superhero in the Marvel Comics library, as recently as 2020 although his first published work for the company was a feature in a 1965 romance comic, Modeling with Millie #44. Speaking of the Marvel archives, it would be much barer without Thomas. He had a hand in creating gobs of prominent heroes and villains that endure in comics, film and television, including the Vision, Luke Cage, Carol Danvers, Adam Warlock, Daimon Hellstrom, Morbius, Valkyrie, Ultron, Yellowjacket and super-teams like the Defenders, the WWII-era Invaders and Marvel’s answer to the Justice League, the Squadron Supreme. Thomas’ lineup of character he helped bring to life, in partnership with artists and writers such as Archie Goodwin, Len Wein, Werner Roth, George Tuska, Neal Adams, Gene Colan John Romita Sr. and of course, the legendary Buscema brothers, John and Sal, is so massive it has its own comprehensive online database. He even came up with the concept for the multiversal What If...? series, which has become incredibly important to the next phase of the MCU.

Oh yeah, and without Thomas, we wouldn't have a certain diminutive and short-tempered Canadian mutant with adamantium claws. Thomas was the first person to brainstorm the idea of a character called Wolverine, a process he shared with me when we talked for my book, Wolverine: Creating Marvel's Legendary Mutant (Shameless plug: It's available at fine independent book stores like this one). Together with Len Wein, John Romita Sr. and Herb Trimpe, Thomas helped turn him from a sale concept into a fully-formed character whose astounding popularity surprises the writer to this day.. "[Wolverine] was really kind of a one-night stand with me. Because once I had made up the idea, I really didn't have any interest in writing the character anymore. I just wanted there to be a Canadian character, and I liked the name Wolverine."

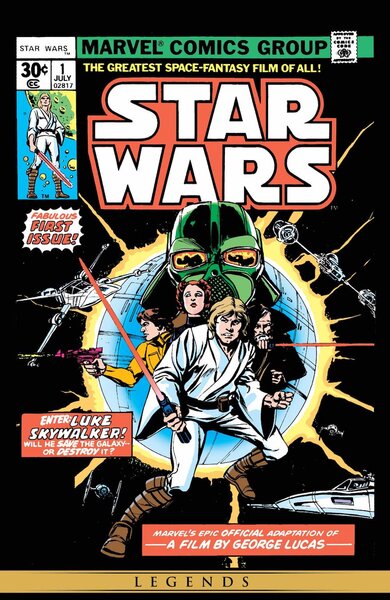

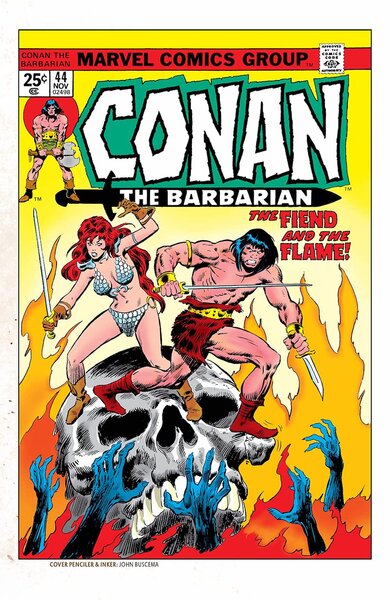

Strangely enough, two of the projects Thomas is most famous for are for characters he did not create. He was the key person in helping launch Marvel's Star Wars comics series in 1977, a title that began as an adaptation of a little-known science fiction movie that would become an ongoing book so important to Marvel that some think it helped the company avoid bankruptcy. He also wrote the first 115 issues of Conan The Barbarian for Marvel, along with hundreds of other stories about Robert E. Howard's famous Cimmerian in companion titles like Savage Sword of Conan during the 70s and 80s. When it first debuted in 1970, the title marked a detour for Marvel from its tried-and-true superhero formula.

"Conan was pretty popular in the paperbacks, but it was a little bit of a risk [to do a comic]," Thomas says. "There hadn't been any successful sword and sorcery books. DC had a couple of issues of a thing called Nightmaster but nothing like that had ever been a success. And we were just very lucky that we got Conan. If we had gotten Lin Carter's Thongor that we originally went after, I don't think it would've worked out as well, but things just fell into place. I never intended to write the book, but I ended up writing it because I had offered the estate a little too much money and I had to write it so that I could drop a couple of pages from my billing, which I couldn't ask another writer to do."

Then, Marvel boss Martin Goodman's infamous frugality came into play, which is how the then-little-known artist Barry Windsor-Smith became the artist on Conan. "Our original choice, John Buscema was too expensive. Goodman, the publisher wouldn't let us spend the money. But it ended up being good for Marvel, because Barry developed and made it such an interesting book and probably even better for Barry because it put him on the map. He was a relatively obscure artist but within a very short period of time, his skills developed very quickly. So it was good for everybody. Good for Barry. Good for me. Good for Marvel. Even good for the Robert E. Howard estate because the comics made the eighties movie possible. So it was a win-win for just about everybody, except maybe Thongor."

It’s a fair point to argue rather successfully that without Thomas, the interconnected success of the Marvel Cinematic Universe wouldn’t be possible. Not just because of the characters he contributed, but because while he didn’t invent the idea of comics continuity, it was Thomas who made tightly-connected storylines and months-long epics a regular occurrence in comics.

Those were concepts that really didn’t exist before Thomas in any consistent form until he joined Marvel. “I guess I had this continuity gene or whatever inside me,” the 81-year-old jokes during an extensive interview with SYFY WIRE.

Thomas says his interest in a shared universe, which Stan Lee initiated during the early days of Marvel’s 1960s heyday with mentions and brief appearances in series such as the Fantastic Four, began during his early days as a fan reading Golden Age comics. “Somewhere very, very early on back there, around 1945 or so, I discovered All-Star Comics, when Flash and Green Lantern had come in and that…was a revelation to me. You could tell there were companies, like DC with the big bullet [logo] and Fawcett, and you could kind of tell them apart by their style and so forth. You'd see Superman and Batman and this character and that character. But when I finally saw five and, actually seven characters together in the same story, even if it was just at the beginning and ending and the separate chapters in between, it made it all more real for me. I began to have this feeling, and I wouldn’t have used the term then, of a universe, of a world.”

“Because from the time I was 5, 6, 7 years old, I was always offended when I would see Superman fight martians in one story and Batman fight martians in another story and they weren't the same. How many martians are there? They don’t even look alike,” he says. “There's like no mention that anybody's ever heard of Aquaman, for example, in the entire universe. Nobody's heard of him outside his own little five or six page strip every month. He’s this world-famous figure but nobody ever mentions him. And that probably started the whole continuity thing. Because then when you start thinking about being a world, you start thinking that means it's a world going sideways with all the characters, it's a world going back and forward the things that happened, you have to remember them. You can't have a first story about this and that five times in a row. If every issue is a new adventure and it's just, all of a sudden, Aquaman starts over with a whole new adventure, no reference to anything that ever happened before, no continuing characters, except for maybe an octopus or something, it just didn't have any reality to me.”

For Thomas, continuity has always been about having respect for the story and the characters at play. “My feeling has always been, and it's just my particular feeling,” he says, “Is that if a company and its writers and artists don't care about continuity, which means the life of their characters in a way and their reality, then why should I care about it as a reader?”

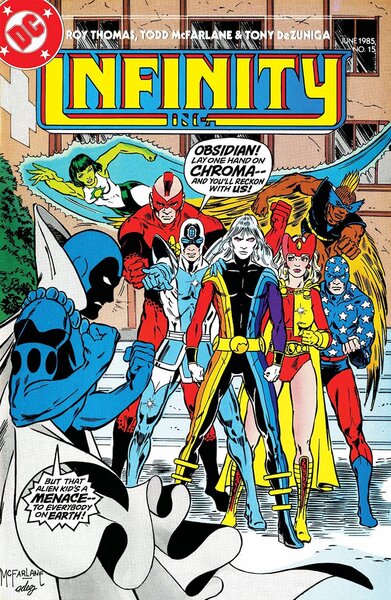

Much like George Perez (another Thomas collaborator at one point), he simply loves working on team comics. He has written the Avengers, the Invaders and the Defenders for Marvel, and the JLA and Justice Society for DC, just to name a few. He even created Infinity Inc. with Jerry Ordway in the 80s, which allowed him at one point to work with then-rising star Todd McFarlane, who has admitted team comics are his kryptonite.

Serialized storytelling really began taking shape at Marvel at the tail end of the Silver Age. During his epic near-six year run on The Avengers, Thomas began weaving long-running subplots that would pay off down the road. He laid the foundation for example, for the Vision and the Scarlet Witch to have one of the most unusual and enduring romances in comics. The Vision, an android character Thomas and John Buscema created as an homage of sorts to a Golden Age Timely Comics character named Aarkus (and whose origin had him be a copy of the original Human Torch), was a character that really only appeared in the Avengers at the time. Thomas was looking to add more romantic drama to the title at the time. "There weren't many women in [Avengers] at the time," he recalls. "There was the Wasp, she's tied up with Henry Pym. There was Black Widow who was kind of tied up with Hawkeye by the time I inherited her, and here's the Scarlet Witch."

He had no interest in her hooking her up with Captain America or Thor, both of whom had their own solo titles. But the Vision was a brand-new character who Thomas had veto power over, meaning that no other writer at Marvel could use the Vision in any substantial way without Thomas' or Stan Lee's OK. "They could use him as a character. They just couldn't change his life or whatever. So the Vision and Scarlet Witch, it was really more a case of they were the boy and girl wallflowers kind of left over at the dance. Everybody else was dancing, and here's the Vision and [Wanda] so, okay. Let's let 'em dance. That's basically how it happened."

The relationship eventually culminated in a wedding after Thomas had left the title and Steve Englehart, another icon of comics Bronze Age, had taken over the Avengers book. "When Steve came in, he took it and developed it far further. Eventually he had the wedding and everything," he says. "I don't know if I would've carried that far. Maybe I would've eventually, but I never really had to think about it. I was just doing it issue by issue. I wasn't thinking ahead, "Will they get married? Will they not get married? Will they split up and do something else?""

Thomas' veto power over a character was atypical in those days, to say the least. Only Stan Lee wielded that kind of power in the Marvel Bullpen, which he reportedly used to keep the Silver Surfer under his influence for a long time. But very quickly after he arrived at Marvel after a short and unhappy stint at DC Comics, Thomas had earned the trust of Stan the Man. It also helped that Marvel, certainly from the mid-60s through the early 1970s, was a relatively tiny operation. "At Marvel, there was just Stan. And there was me at at least through at least say, 1974," he remembers.

Thomas was the first person to ever get a writing credit on the company's top-selling comic, the Amazing Spider-Man, other than Stan. He also followed his mentor as Marvel's editor-in-chief in 1972 when Lee became publisher. Incredibly, Thomas continued to write, scripting the Fantastic Four while overseeing Marvel's growing slate of titles. Lee's influence on Thomas' career can't be overstated. Much like Lee, he became well known for his writing and editing acumen. One way he differed from Lee was in his relationships with his artistic partners. Lee is regarded by many as one of the greatest editors in the history of comics, but Thomas shared insight into some ways that helped create conflicts between Lee and Marvel artists like Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and Wally Wood.

"It's inevitable when you deal with an editor, you're always gonna be annoyed at him at some stage. I mean, I got mad enough at Stan to want to quit a few times," Thomas admits. "I think one of the things that Stan did that was a mistake, a flaw in his system, which was otherwise pretty good, because he was an enthusiastic comics pro. He wasn't blase like a lot of these DC editors were who really would've rather been in another field, Stan would've too. He wasn't really a comics fan, but once he was in it, he was a fan. He admired the artists and I think he respected them more than a lot of the DC editors did at that time. But at the same time, because he was so interested in getting things [published] and he had so many things on his mind, he didn't like when anything got in his way."

"So if an artist had a different viewpoint and he didn't like it," Thomas continues, "He just would kind of run over it or insist it be done his way. And that's okay. He had the right to do that and maybe he was aesthetically right. And certainly it worked out pretty well for Marvel, but could it have also worked out sometime if the other people had an idea and he had given in a little more."

With some artists, some problems proved insurmountable. A few pencillers, no matter how skilled they were, struggled with the Marvel Method, in which the artist was expected to plot out a story from a brief synopsis from the writer, who would then go in and insert the dialogue after the drawn pages were done. The legendary Wally Wood, for example, was one who did not like this particular workflow, which is one reason his tenure at Marvel did not last. "If Wally Wood didn't like the idea that he was gonna do a lot of the plotting on Daredevil, then he was right to walk away and he did," Thomas says. "But Stan let him write one of the books. If he'd stuck around, he and Stan could have worked out something like he did with Ditko where he'd have been happy. Stan loved Wally so much that when he first came to Marvel, he got his name put on a cover, right? That's when Kirby wasn't getting his name put on a cover, but Wally Wood did. Because Stan loved Wally that much as an artist. But they were on such different wavelengths. I mean, Wally would sit around in Stan's office dribbling cigarette ashes on his floor and it was just a lot of strange things."

Thomas admits Wood and other Marvel artists had legitimate complaints about the Marvel Method and Stan's demanding style, but notes that it was typical for the industry at the time. "That was the conditions of employment that they kind of grew up in. At least it was in place by 1965 when I was there," he says. "And if you didn't want to do that, if you didn't feel that part of the artist's job was to work with a writer and tell the story and add to it, not just draw a picture, then you should go somewhere else. Like when I brought Ramona Fradon back, and she didn't like working the "Marvel Method". So she drifted over very quickly to DC, where she was more comfortable and that's fine."

The legacy of his former boss and longtime friend has undergone extensive re-examination in recent years. Several books, including Abraham Riesman's True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee, have taken a harsh stance on Lee's penchant for self-promotion, accusing him of claiming far too much credit for the creation of Marvel's stable of characters at the expense of co-creators like Kirby, Ditko, et al. Thomas isn't having any of that.

"One of the biggest misconceptions somehow is that Stan rode to glory on the backs of various artists. Now, I'd be the last person in the world to claim that he didn't get the best he could out of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko and a lot of other people, but it was kind of a coincidence that he managed to get some of the very best and most commercial work out of those people," Thomas says. "Kirby was never any more successful in comics than he was in that decade or so that he worked with Stan. I was a fan of Steve Ditko before Spider-Man, because I liked the Captain Atom stuff that he had done at Charlton. But if it hadn't been for Spider-Man and Dr. Strange, I don't think Steve Ditko would now have a reputation as one of the great comic book artists ever. And I'm saying that as a Steve Ditko fan, too, since I was in my teens."

As he continues to talk about Lee, Thomas gets more passionate in his defense of the man who he learned so much from. It's no secret how close the two were. Ever since he passed that writing test and joined the Bullpen in 1965, he has been linked to Lee. Thomas saw him for the last time on November 10, 2018, at Lee's home in Los Angeles. He died less than 48 hours later.

So when people go after Lee and question his contributions to the Marvel mythos, it's understandable that his former protege takes it personally.

"There are people who simply think that Stan came along and that all he did was make up some decent dialogue," he says. "Stan was the editor. So he had to keep the thing going. There was nobody else. It wasn't Martin Goodman and it wasn't even Jack Kirby, who was not a universe builder at that stage. And of course, Stan hadn't been either. Stan was the guy who was the puppet master of the whole thing, but on more of an instinctual level. He wasn't setting out to do this, but it grew. And he sort of learned over the period of that first couple of years, what he was doing and what he should do. And he just got better and better and better at it."