Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

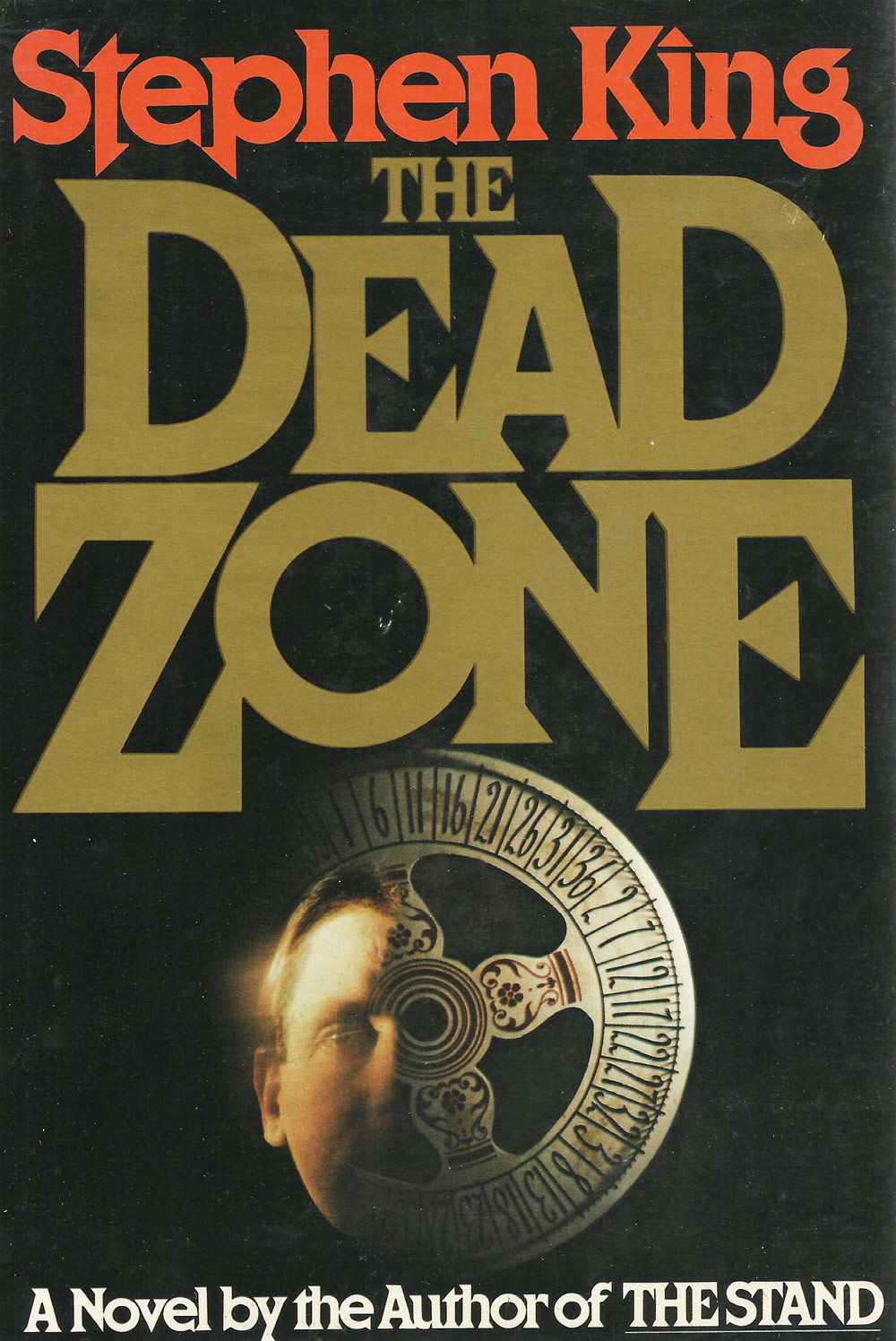

40 years later, Stephen King's The Dead Zone is scarier than ever

There are not very fine people on both sides in The Dead Zone. Stephen King makes sure you know that right away.

The very first time we meet Greg Stillson — the rising political star who becomes the villain of King's 1979 novel — he's selling Bibles door to door when he comes across a very loud dog. When he's sure no one is home, he gleefully kicks the dog to death. Ambiguity can be a powerful element of horror fiction — is the house really haunted or are you just going crazy? — but mere pages into The Dead Zone, King wants to make it clear that a bad man with big ambitions is stalking the landscape.

It's been four decades since The Dead Zone, King's fifth novel (not counting the ones he released as Richard Bachman), was published, and revisiting it now reveals that it has only grown more frightening with time. King could not have known in 1979 how eerily prescient his novel would feel in 2019, but here we are. This taut, rather intimate story of obsession, intuition, and pure dread has somehow become a dark mirror for the way so many of us live now, and its relevance serves to further cement King's status as a titan of genre 40 years and dozens of novels later.

The Dead Zone follows Johnny Smith, a young teacher who gains the ability to read minds and even see the future when he touches someone, or even touches something that person has owned. After using this ability to help solve a string of murders, Johnny flees a potential life as a famous psychic, but remains haunted by his dying mother's plea to do something with his gift.

Johnny's retreat into relative obscurity happens to coincide with an upcoming election, and he becomes fascinated with politics, and with shaking the hands of candidates in an effort to see what kind of leaders they might be. When he shakes Stillson's hand at a rally, he has a vision of the candidate rising through the ranks to become president, and then starting World War III. Horrified, Johnny becomes convinced that only he can stop Stillson's rise and thus save billions of lives, setting the two men on a collision course.

In his memoir On Writing, King explained that The Dead Zone arose from the question of whether a political assassin could not only be "right," but also become "the good guy" in a story. To achieve this, he needed to tip the scales in Johnny's favor by making sure his readers knew from the start that Stillson was a bad man. Here's how he explained it:

"These ideas called for a dangerously unstable politician, it seemed to me — a fellow who could climb the political ladder by showing the world a jolly, jes'-folks face and charming the voters by refusing to play the game in the usual way."

"Dangerously unstable" turns out to be a relatively polite way to describe Greg Stillson, a man who embraces violence behind the scenes and, when the cameras are rolling, puts on a smiling showman persona that includes wearing a hard hat at rallies and throwing hot dogs into the crowd to prove how purely American he really is. His Congressional platform includes a promise to make it rain whenever anyone needs it, a promise to shoot all of America's pollution into space, and a pledge to "throw the bums out" of Washington.

In one of the novel's most memorable scenes, Johnny and his employer — a wealthy businessman named Roger Chatsworth — watch an evening news recap of a Stillson rally. Johnny watches in amazement as Stillson charges up and down the stage like a bull and flings hot dogs at ecstatic supporters, stunned that such a man could be perceived as a serious candidate. Roger points out that Stillson's New Hampshire district is full of blue-collar people who want something to change, and that they might just elect Stillson to send a message to Washington.

"He's a clown, so what? Maybe people need a little comic relief from time to time," Roger says.

So, we have a candidate who likes to put on hard hats to show he's a man of the people, makes promises he can't possibly keep, and declares he's going to "throw the bums out." Move a few words around ("Drain the swamp," anyone?) and it's pretty easy to see where the parallels are, and why The Dead Zone rings so true in 2019. Just this week, members of Congress have gone on TV to assure the public that a very serious-looking president was just joking about asking another country to investigate a political rival.

"He's a clown, so what?"

Yes, The Dead Zone is a novel in which the villain is an openly, gleefully awful politician whose thirst for power knows no bounds. King tells us that right away, and never lets up in describing Stillson as the lowest kind of charismatic opportunist, but Stillson is not actually what makes The Dead Zone so scary, whether you were reading it in 1979 or are cracking it for the first time in 2019. Double-talking politicians are nothing new, after all, even if they are enjoying a particularly robust era right now. No, what makes The Dead Zone so frightening right now is Johnny Smith.

King spends the entire first half of the novel only occasionally visiting Stillson, devoting most of his narrative energy to Johnny's tumultuous inner life. The lack of ambiguity in King's portrayal of Stillson is even more evident in his portrayal of Johnny. He's a plainly decent guy who happens to have been saddled with an unthinkable power, and King makes it very clear that he's not imagining it. He also makes it clear that he doesn't want it, doesn't enjoy it, but because of his inherent goodness, he finds it very hard to run from it. It's that inability to turn a blind eye, to completely hide from the world's problems, that makes Johnny's descent into what he feels is necessary violence so compelling, and even relatable.

At no point in the novel does King advocate political assassination, of course, but if you take the heightened reality of The Dead Zone and shrink it down to your own (hopefully) nonviolent life, you start to see parallels. Johnny's obsession with the election mirrors our own obsession with our political climate, which feels like an inescapable maelstrom even on good days. His anxiety over what to do with his gift mirrors our own anxiety over how, exactly, we can make a difference when there are 20 different world-altering issues in play at any given moment.

Most strikingly, though, the dark gift that tells him the world is going to end if this evil man is allowed to push forward any longer mirrors our own frightening intuition, the thoughts that keep us up at night. How do we convince people who don't seem to want to listen that the bad feeling we have about the future is real? How do we fight something so much bigger than ourselves when we don't have psychic powers and don't want to give in to violence? How do we live with that dreaded sense that most days we're just shouting into the void (The Dead Zone, if you will), trying to change hearts and minds that just don't want to be changed? That's the inescapable dread at the heart of The Dead Zone that makes it so scary 40 years later. Thankfully, though, the novel also provides an answer to this question, one that offers at least a little hope in the form of some of Johnny's parting words.

"We all do what we can, and it has to be good enough, and if it isn't good enough, it has to do."

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author's and do not necessarily reflect those of SYFY WIRE, SYFY, or NBCUniversal.