Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

An amateur astronomer has discovered a nearby galaxy!

I am a big supporter of amateur astronomy for a lot of reasons. First, it gets people outside and looking up, which is just a good thing to do. It also fosters an appreciation for the sky and the beauty in it. I consider myself an amateur astronomer, too, taking my own 'scope out when I can. And, sometimes, amateur astronomy helps advance science in ways that are not so easily done by professional astronomers.

Take, for example, the case of Donatiello I. It's what astronomers call a dwarf spheroidal galaxy, which is pretty much what the name implies: It's a small, kinda sorta round galaxy. These types of galaxies are notoriously faint, and difficult to spot even at modest distances. Quite a few are known near and around the Milky Way and a few other very close galaxies. The problem with finding them, though, is a well-known paradox of professional astronomy: The big telescopes needed in general to see these faint fuzzies usually have a narrow field of view, making it a stroke of luck to find one.

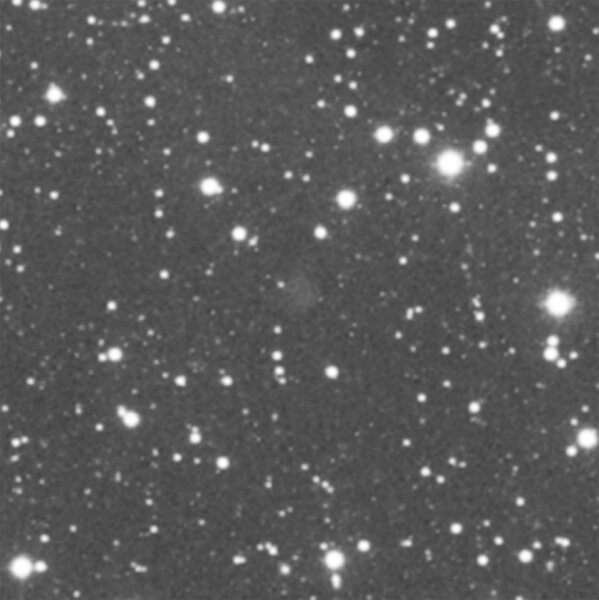

Donatiello I is just such a beast, so faint that it would be incredibly easy to overlook even in deep images taken by meter-class telescopes. And that's why this story is so cool. Donatiello I is named for Giuseppe Donatiello, the amateur astronomer who discovered it.

Even better? He was using a 12.7 centimeter telescope he assembled himself from parts of other telescopes!

Even even better? He was actually looking for dwarf galaxies when he found this dinky example of one!

I love stuff like this. Donatiello was observing from a park in southern Italy (near the "arch” of the boot) where skies are dark. He was taking images of the sky in the area around the Andromeda galaxy, another big spiral galaxy like ours, and the nearest one to us; a fair place to look for dwarf spheroidals, which are commonly seen as satellites to bigger galaxies.

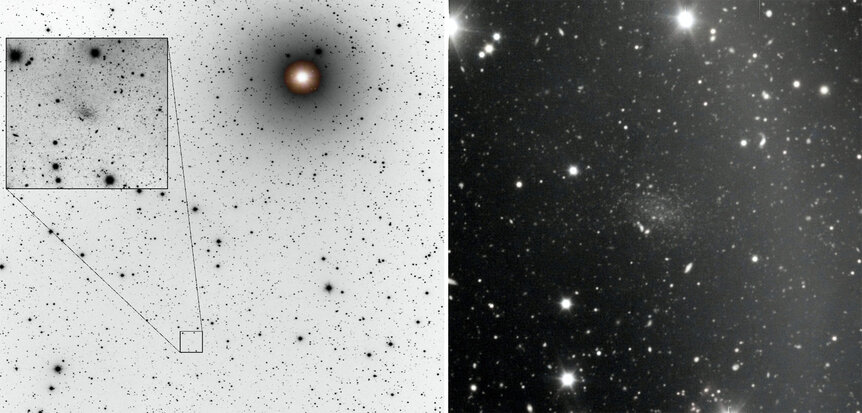

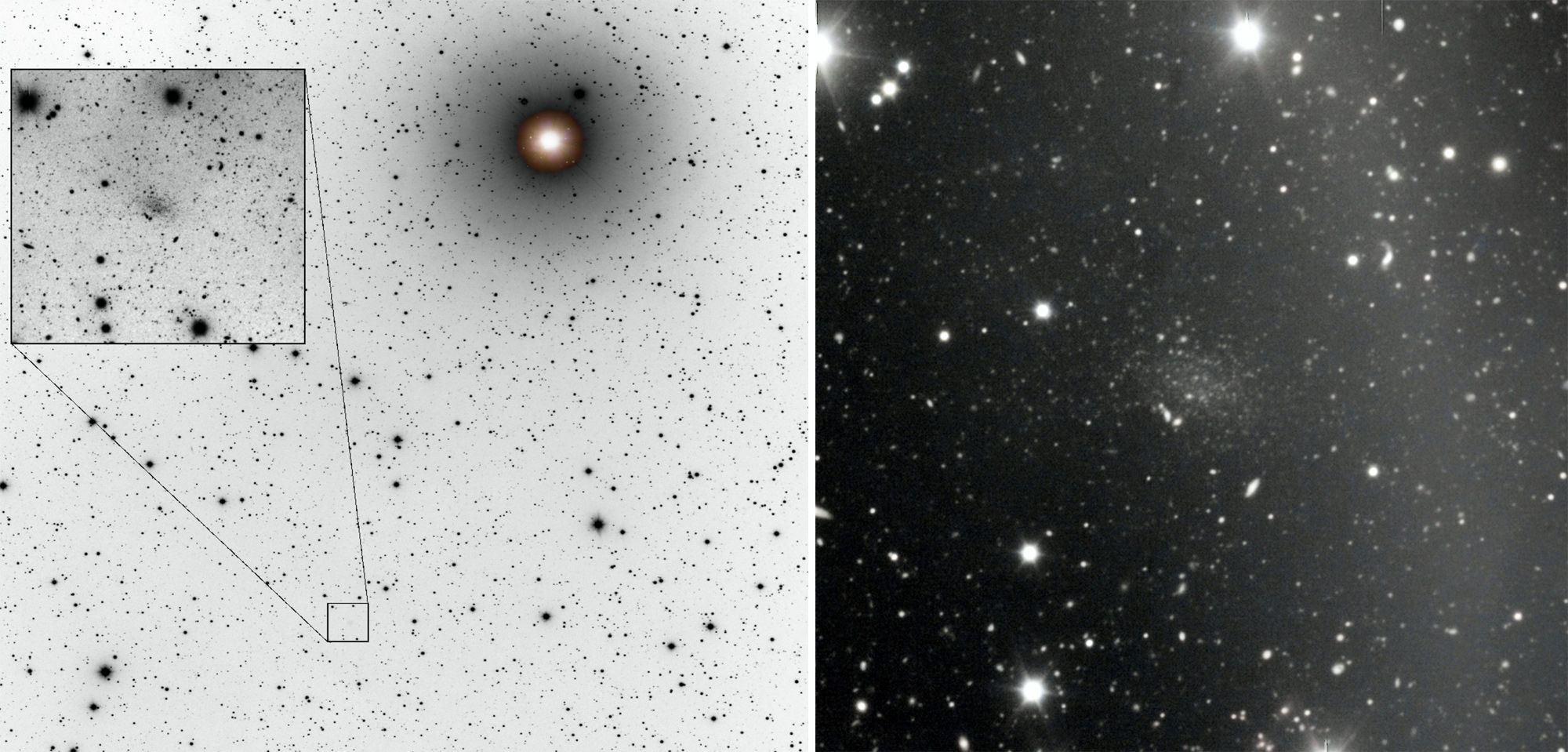

He was using an off-the-shelf astronomical camera and later noticed a very faint smear of light in one of the images. He posted the image to Facebook, and it was spotted by David Martínez-Delgado, an astronomer at Heidelberg University in Germany. He secured followup observations using the mammoth 10.4-meter Gran Telescopio Canarias, confirming this was indeed a nearby dwarf spheroidal galaxy… but not as nearby as they first thought.

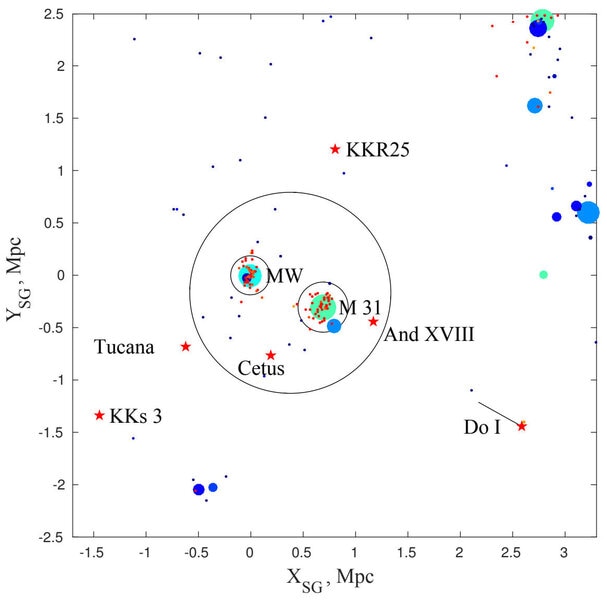

Inititally they thought Donatiello I was a companion of the Andromeda Galaxy, but when Martínez-Delgado and his team dug into the data they got a surprise. Using a couple of different methods to measure the distance, they found it was about 10 million light years away, far beyond Andromeda (which is a quarter that distance from us).

In fact, Donatiello I is well outside even the Local Group, a small collection of galaxies to which Andromeda and the Milky Way belong. That surprised me; not many dwarf spheroidals are known at this distance (because they're so faint). Only a handful have been discovered outside the volume of space occupied by the Local Group.

But that raised another possibility. That distance is about the same as the distance to NGC 404, a smallish disk galaxy also about 10 million light years away (nicknamed "Mirach's Ghost," because it lies very close in the sky to the bright star Mirach, making NGC 404 hard to spot… which inspires a pretty good pun, too). If the distance to Donatiello I is accurate, that puts it just about 200,000 light years from NGC 404, close enough that they might be associated with one another (though that distance is a minimum, since we can't see in three dimensions; it could be closer to us and coincidentally aligned with NGC 404). That's cool, because that means learning about one may provide insight into the other.

Donatiello I is a little bit odd. It doesn't seem to be making any new stars, and tied to that it also doesn't appear to have much gas in it, possibly due to losing it somehow. It's not clear, if it's on its own in the depths of space, how the gas got stripped from it.

Interestingly, though, there are indications that NGC 404 has had interactions with smaller galaxies in the past, and has star formation going on in it. That's unusual, because NGC 404 is a lenticular galaxy, a lens-shaped disk galaxy, and these usually lack gas and therefore don't have ongoing star birth in them. It's also a mildly active galaxy, meaning the massive black hole in its core is actively feeding, or more likely snacking. Some active galaxies blast out high energy light, like ultraviolet and X-rays, but NGC 404 isn't that energetic. That happens too when a bigger galaxy collides with and essentially eats a smaller one; the ensuing gravitational shakeup can drop gas to the core where the black hole resides. A near miss can do this as well. NGC 404 isn't a terribly big galaxy, so even a small galaxy can ring its bell pretty well.

While the evidence is circumstantial, it does make one wonder if Donatiello I and NGC 404 had an encounter some time in the past. It would explain a lot. However, that's really hard to tell, especially since the distance to Donatiello I isn't well nailed down. The researchers are hoping to get time on Hubble Space Telescope to observe it, so that they can investigate the stars in it more precisely and use them to get a better distance measurement.

I love this sort of story, what we call Pro-Am astronomy. Professionals can't look at the whole sky, because really it's just too dang big. Amateur 'scopes, equipment, software, and expertise has gotten so good in recent days that they have a serious and important impact on the science of astronomy, and they can cover parts of the sky professionals simply can't.

We can all make contributions to science. Maybe not the same way Giuseppe Donatiello did, necessarily, but there's still plenty of sky to search for all sorts of treasures.