Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Astronomers find an exoplanet where an exoplanet shouldn’t be

Over 4,000 exoplanets — alien planets orbiting other stars — have been found by astronomers so far.

There are a variety of ways to find them, most of which use indirect methods, but one of the coolest is quite direct: Getting actual images of the planets near their host stars. Called direct imaging, this technique has been used to find dozens of planets.

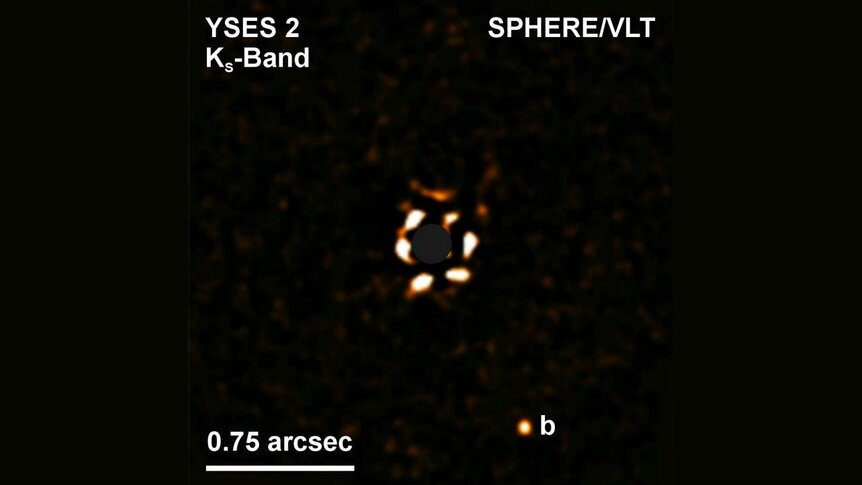

A team of astronomers has targeted 70 nearby stars to look for such exoplanets, and have just announced a new one: YSES 2b, a giant planet orbiting a star just 360 light years away.

We've seen some similar to this before, but in this case, this planet is special. For one thing, it's orbiting a star that will one day be very much like the Sun. For another, it's orbiting at least 16.5 billion kilometers from the star, a whopping 110 times farther from its star as Earth is from the Sun!

That's a very, very long way, and what it's doing that far out is a mystery.

Direct imaging works best to find very young planets, up to a few dozen million years old. Planet formation is a violent, energetic process, so these young planets are hot. They glow strongly in the infrared (IR) part of the spectrum, so astronomers use IR cameras on big telescopes to find them. This has a side benefit that stars are typically fainter in the IR than in visible light, making it easier to see any planets.

The astronomers who found this new planet run a survey called the Young Suns Exoplanet Survey, or YSES, and they're looking at a nearby clump of young stars called the Lower Centaurus Crux subgroup, a part of a much larger loose group of stars called the Scorpius-Centaurus association. These stars are very young, roughly 14 million years old (the Sun is 4.6 billion years old, for comparison, so these stars are babies) and located just 350 or so light years away, close enough that an exoplanet may be separated from its star enough to spot in images.

We know that stars more massive than the Sun tend to have more massive planets, so to avoid any biases like that the survey looks just at stars with masses similar to the Sun. They're targeting 70 such stars in the group.

YSES 2* is the second star they've looked at where they've found a planet (they've observed about 45 others, but they're still working on looking for planets around those). It has a mass of 1.1 times the Sun's, so it's very similar, though cooler at the moment (over time it will likely get hotter once it settles down and becomes stable). It's about 360 light years from us.

The planet looks like a background star, and is so far from the star that seeing any orbital motion isn't possible (it'll be many years before it moves noticeably). To confirm an exoplanet is a companion to a host star, the team takes images of each star a year apart. Stars are all in motion as they orbit the center of the galaxy, and the targeted stars are close enough to Earth that this motion appears large (like when you're in a car and trees whiz past while a distant mountain barely appears to move at all). If the candidate planet truly is a companion, it will move along with the star. If it's a background star it won't.

Images taken a year apart show the object truly does move with the star, so it is a companion. Using physical models of how planets cool after formation, they find it has a mass of somewhere between 5 and 8 times that of Jupiter, with a most likely mass of about 6 Jupiters, making it a true planet. They have thus dubbed it YSES 2b.

Thing is, what's it doing so far from the star? There are two known ways to make a massive planet. One is what's called direct collapse, where it forms from the collapse of a part of a gas cloud, just like a star does. This can in fact make something that distance from a star (it's how binary stars form, for example), but the weird thing is it's hard to make something so lightweight. A planet forming that way should be far more massive than YSES 2b.

The other method is called core accretion, where small particles in a disk around the star stick together, grow bigger, and then get big enough to draw material in via gravity. However, the disk around a star is pretty meager as far out as YSES 2b is, so in that case it's too massive to have formed that way.

The likely explanation is then that, like most gas giants, it formed via core accretion closer in to the star where the disk is thicker, and then got tossed out to its current distance after encountering another giant planet orbiting the star; the gravity of that planet could eject it out to that distance.

The problem there is that no other planet like that is seen in the observations. It's possible it's so close to the star that the glare makes it too hard to find. That seems likely to me, since we know things like this can happen, whereas the other two possibilities are less likely. Still, it would be nice to know for sure.

That's why YSES 2b is an important catch. If the team finds more, they hope to be able to see trends in the planets that will help them understand how planets form around Sun-like stars, and how some form at or get to such remote distances. Although our own solar system may not have a planet like that (though we might), it helps us understand how our own system formed as well. There are still a lot of things we don't know about planetary formation processes, and every young planet found is a step toward advancing that knowledge.

*A lot of surveys tend to name the objects they find after the survey in question. The star has a more formal name of 2MASS J11275535-6626046, which is easier to look up in databases, but YSES 2 is good enough for here.