Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

BepiColombo's first kiss with Mercury!

Over the weekend (on October 1), the joint European/Japanese Space Agencies spacecraft BepiColombo passed Mercury for the first time, skimming just 199 kilometers above the planet’s surface!

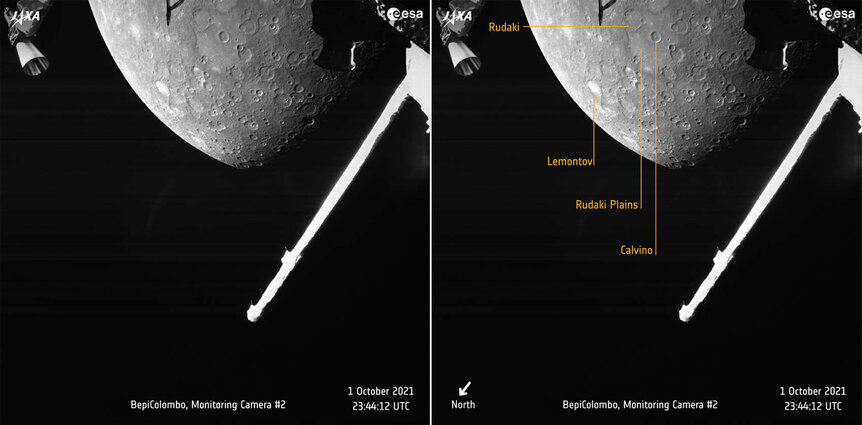

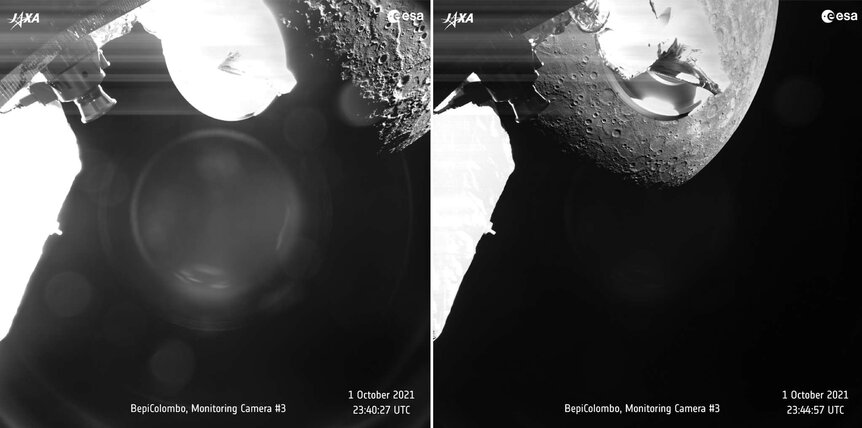

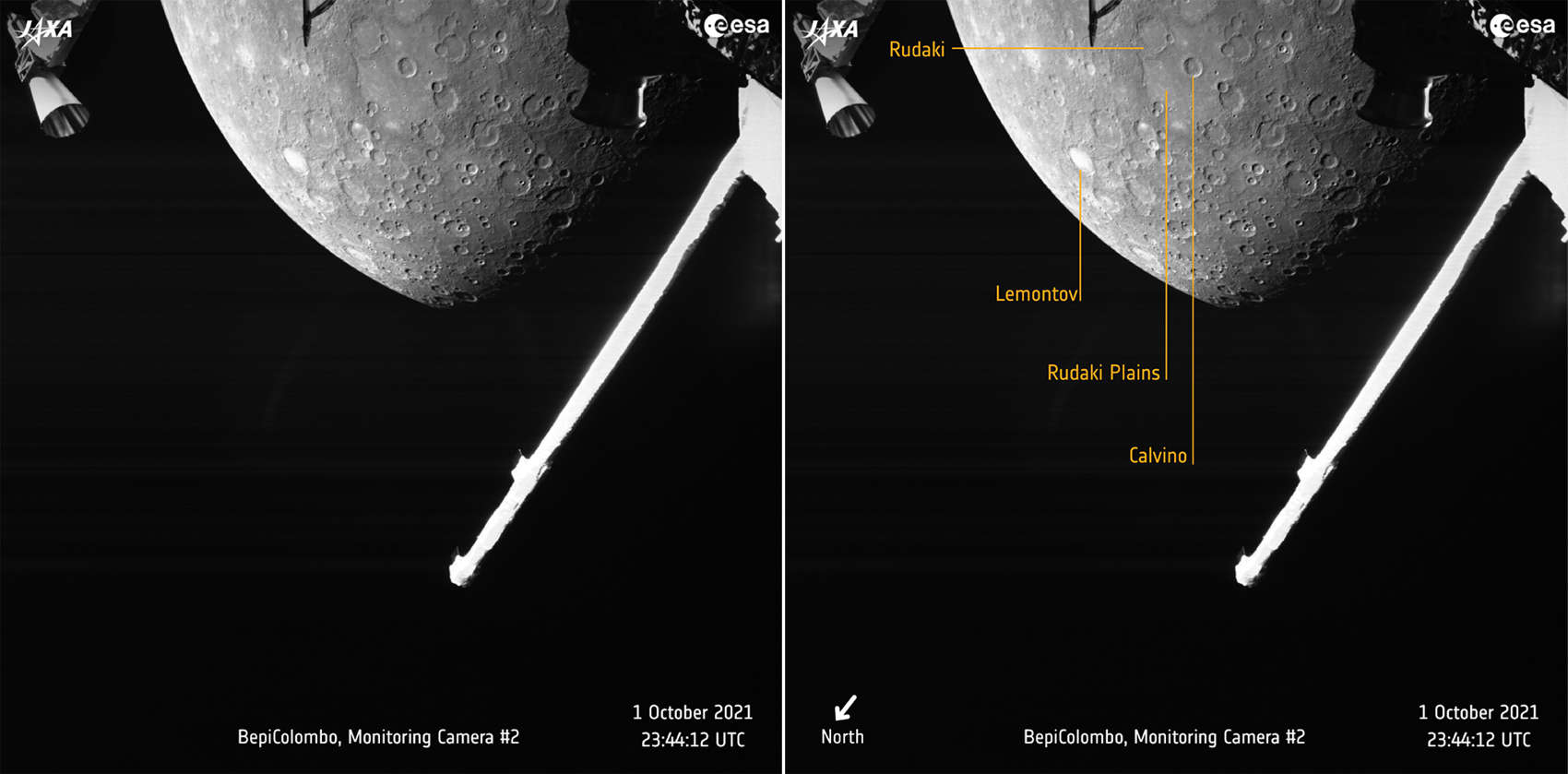

That’s a seriously close shave, but it was over Mercury’s nightside so no images were taken. Not long after, though, when it was 2418 km away, it took this extremely cool shot of innermost planet:

Whoa. On the left is the original shot and on the right a few craters are annotated. You can also see parts of the spacecraft in the foreground. I’m always amazed at how much Mercury looks like our own Moon: Gray, airless, and just covered with impact craters. But in reality the two are very different, which is why sending probes to Mercury is a good idea.

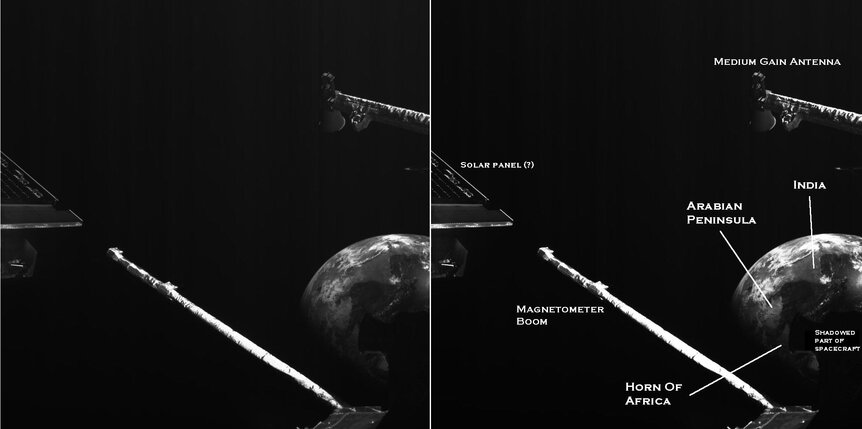

BepiColombo is an ambitious mission. It’s actually three spacecraft, temporarily mated together for the journey (which I will get to in a moment, and yeah, it’s a journey). There are two science spacecraft: The Mercury Planet Orbiter (built by the Europeans) and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (nicknamed Mio and built by JAXA, the Japanese agency). These are loaded with instruments to investigate Mercury’s geology, its surface mineralogy, its magnetic field, and to measure the characteristics of the planet’s huge liquid/solid iron core, which stretches 85% of the way from its center to its surface.

The Mercury Transfer Module is the delivery vehicle for the two science craft. It has solar panels for power — useful when you dip down so close to the Sun; Mercury’s elliptical orbit takes it from roughly 46 to 70 million km from the Sun.

The module uses ion propulsion for thrust. Unlike big, noisy, and heavy chemical rockets (the kind you usually see) this uses an electric field to accelerate xenon ions out the back at extremely high speed, far faster than chemical rocket exhaust. The thrust is incredibly low, since it uses very little xenon at any given moment, but it can thrust for months, whereas chemical rockets run through their fuel supply much more quickly. So it uses very low acceleration over very long periods of time to change trajectory, with the benefit of using up much less precious mass during the initial launch.

BepiColombo launched on October 20, 2018. Here’s the fun bit: Getting to Mercury is hard. You can’t just throw something toward the Sun and hope to get to your destination! The Earth orbits the Sun at over 30 km/second, so you need to negate that motion to drop down toward Mercury. That takes a lot of thrust, in general more than our current technology can easily provide to a spacecraft (even with ion engines).

So BepiColombo pulls a Robin Hood on planets.

When you’re talking orbital mechanics you have to think in terms of energy. Earth moves around the Sun in a higher energy orbit than Mercury does (or, in other words, it takes a lot of energy to get away from the Sun, from Mercury to Earth, so going the other way you have to remove that energy). At launch, BepiColombo has too much energy, so engineers designed a devilishly clever path for it over time that takes energy from the spacecraft and gives it to the planets!

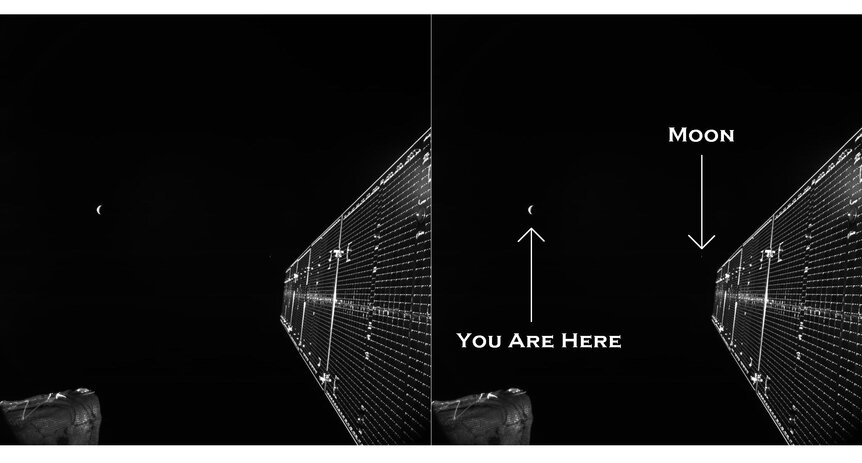

It launched into an elliptical orbit that took it a bit farther from the Sun than Earth, then dropped it down a bit closer in. It then passed Earth on April 10, 2020, giving a little bit of its energy to Earth. That dropped the spacecraft down toward the Sun… and in return actually moved Earth a little bit farther from the Sun! That scales with the mass ratio of the two objects, and since Earth is somewhat more massive than BepiColombo — about a sextillion times (1021) — our planet didn’t move enough to even measure.

It then dropped down to just inside the orbit of Venus and on October 15 2020 did essentially the same thing. It used the gravity and motion of Venus to put itself into an elliptical orbit that passed Venus a second time on August 11, 2021. It gave enough energy to Venus to drop it down toward the Sun even more.

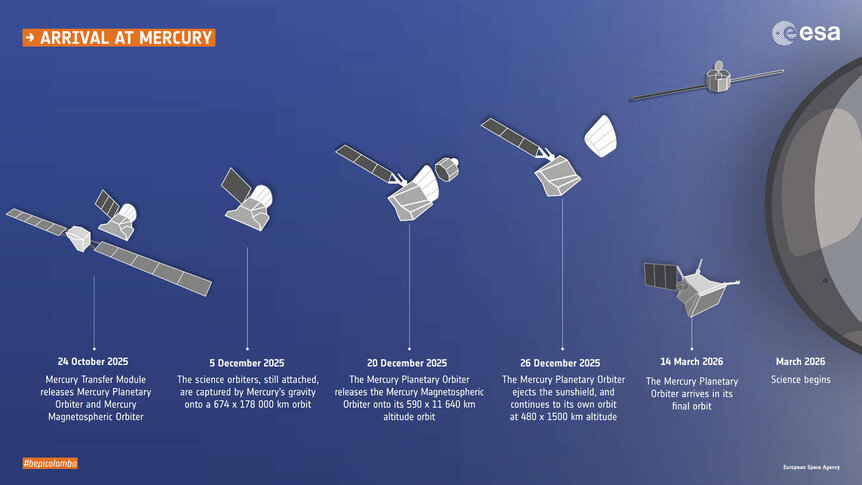

But it still has too much energy, so on October 1, 2021 it flew past Mercury to dump more of its energy — and send back those amazing images. But this is just the first pass! It’s still on a trajectory that’s too elliptical, so it will pass by Mercury five more times, eventually circularizing its orbit around the Sun enough that it can then slowly approach the planet and go into orbit. It should achieve that goal on December 5, 2025.

Mercury is a weird place. It’s the smallest planet, but also very dense. The surface is rocky, and rock is low density, so it must have a dense iron core. NASA’s phenomenal MESSENGER spacecraft orbited Mercury for four years, discovering quite a bit about it, including finding the core was bigger than expected and had to be at least partially liquid to generate Mercury’s magnetic field. BepiColombo will follow-up on that getting more data to help scientists understand why Mercury is the way it is.

One idea is that Mercury was bigger originally and then got whacked, hard, by a smaller planetesimal (objects in the early solar system between 1 to 100 km in size from which the planets formed). This impact stripped off much of Mercury’s crust and mantle, leaving behind a planet with what appears to be an outsized core. Data from BepiColombo could support or refute this hypothesis.

Mercury is difficult to study from Earth because it’s always near the Sun in the sky, making it hard to observe. But it’s also hard to get there, so only two spacecraft (Mariner 10, which did three flybys, and MESSENGER), have visited it. BepiColombo will be the third, and will hopefully answer a lot of questions about this enigmatic planet.

And hopefully raise even more questions. In fact that’s a guarantee; the more we learn about anything in the Universe, the more we find out we need to learn.

Ad Mercurius, BepiColombo. Only five more passes to go.