Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Mysterious burial of a child 8,000 years ago is now unearthing secrets of a lost time

Thousands of years ago, a child, no more than eight years old at the time of death, was laid to rest. The child’s cheeks and forehead were painted with ochre, their head laid on a stone also colored with ochre, and their arm and leg bones were removed before the body was finally buried in a cave. This grave would remain undisturbed for millennia.

Child burials from the mid-Holocene are exceedingly rare. This is why this find is so significant to the team of Australian National University archaeologists who discovered it in Makpan Cave on Alor Island, Indonesia. This is the only known complete child burial that remains from that period. It is also one of a kind in the region, and while there are some parallels to adult burials from that era, not everything is the same. Until now, funerary rites associated with children from that period were next to unknown.

"From 3,000 years ago to modern times, we start seeing more child burials and these are very well studied,” said archaeologist Sophia Samper Carro, who led a study recently published in Quaternary International. “But, with nothing from the early Holocene period, we just don't know how people of this era treated their dead children. This find will change that."

What Samper Carro and her team do know is that arm and leg bone removal is not an anomaly. Similar evidence has been found in Java, Borneo, and Flores. Long bones were often removed and taken elsewhere, though it remains unclear whether they were disposed of, buried separately, or treated some other way. Many ancient peoples would keep bones and even mummies of the dead with them. The Chinchorro of Chile would mummify their dead and keep them in the home as if they were still alive, apparently as a way of staying close to those who had gone on to the afterlife.

There were other ancient cultures who also removed bones. Even older than the Indonesian child, Paleolithic remains found in the French cave of Grotte de Cusac suggest that some bones were taken away or moved around after skeletonization, which could suggest a way of actively communing with the dead.

"We don't know why long bone removal was practiced, but it's likely some aspect of the belief system of the people who lived at this time,” Semper Carro said.

Missing arm and leg bones could suggest that the people who lived on Alor Island practiced excarnation, or the removal of flesh and organs from the dead before burial. This is a ritual known to have been carried out by the Chinchorro, except they kept the entire skeleton intact when they replaced skin and flesh with clay, vegetable fibers, and animal hair to complete the mummy. It could also mean that the customs of these mysterious people were similar to the living who regularly visited their dead at Grotte de Cusac. Nobody really knows.

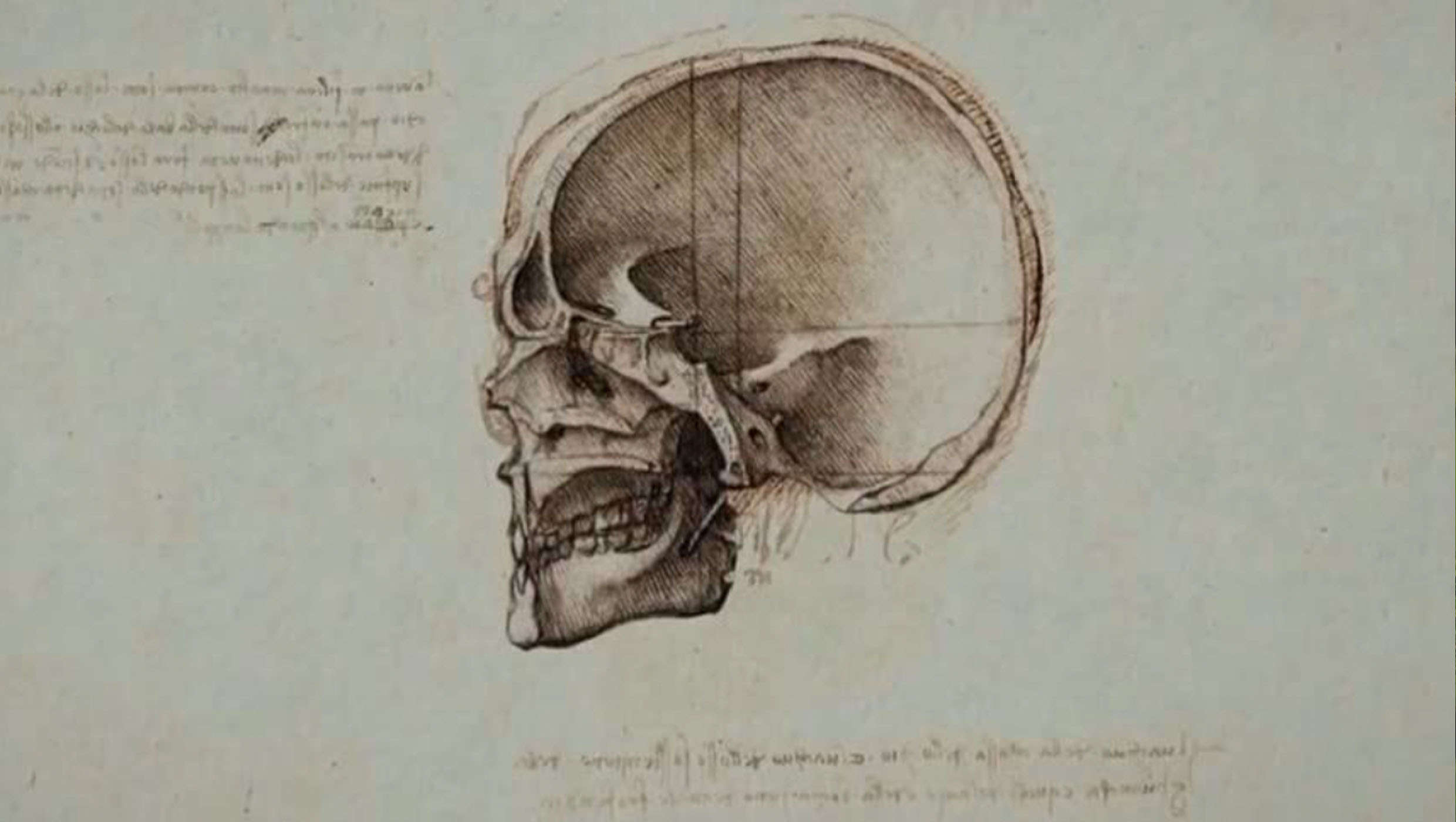

Another unknown that arises from this burial is why the child had the teeth of a 6-to-8-year-old but the skeleton of a 4-to-5-year-old. Research that Semper Carro had previously done on adult skulls from Alor Island revealed small skulls that could have been the result of these fishermen from the past relying mostly on fish and other marine life, which could have meant general malnourishment and protein saturation. When excess protein cannot be used effectively by the body, bone disorders are just one of the adverse effects.

It is also possible that the skeletons of the child and adults found on Alor Island could indicate some sort of impact form the environment or genetic isolation. More research is needed to find out, but in death, these people are slowly being brought back to life.