Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Can a planet be bigger than its star?

I get questions.

After posting an article here on the blog about an extremely low-density "superpuff" planet, I got an interesting question on Twitter:

["Have we ever found an exoplanet that was larger than its host star? Is that possible?"]

My first reaction was, "Yes! Kinda." And then I thought about it a little more, and realized the answer is actually, "Yes! But if you mean a star like the Sun, it's unlikely."

Explaining it would be a bit much for Twitter, but as it happens I have a blog! So here's more about this.

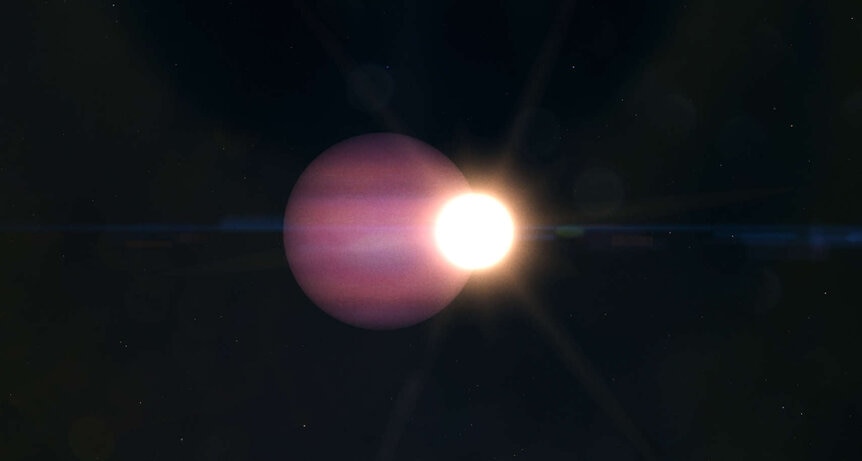

That first reaction of kinda was due to thinking about a white dwarf. This is the remnant of a star that was once like the Sun but died, shedding its outer layers and leaving only the core behind. That core — the white dwarf — is only about the size of the Earth. If the star had any planets bigger than Earth orbiting it before it died, it's possible that some will survive, and you get a planet bigger than its star. In fact we've seen a system like this, so yes, it can happen, and we're done. Easy peasy.

Except a white dwarf isn't a star like the Sun, not anymore. So maybe that doesn't count. That brings me to my second reaction, where a planet is bigger than its star for a star like the Sun.

What's the difference? A white dwarf is dead, not creating energy anymore, just sitting there getting cooler. The Sun is still fusing hydrogen into helium in its core in a nice, stable fashion, as it has for over four billion years and as it will for roughly 6 or 7 billion more. Stars like this are called main sequence stars, for historical reasons (you can find out more about that in my Crash Course Astronomy episode on stars).

The Sun is ten times the diameter of Jupiter, and it turns out you can't get planets much bigger than Jupiter. If you add mass to them, they get smaller, not bigger. So clearly you can't get a planet bigger than the Sun.

What about smaller stars? The smallest stars are dim red dwarfs, barely massive enough to maintain fusion in their core, and the smallest they can get is, well, pretty dang small.

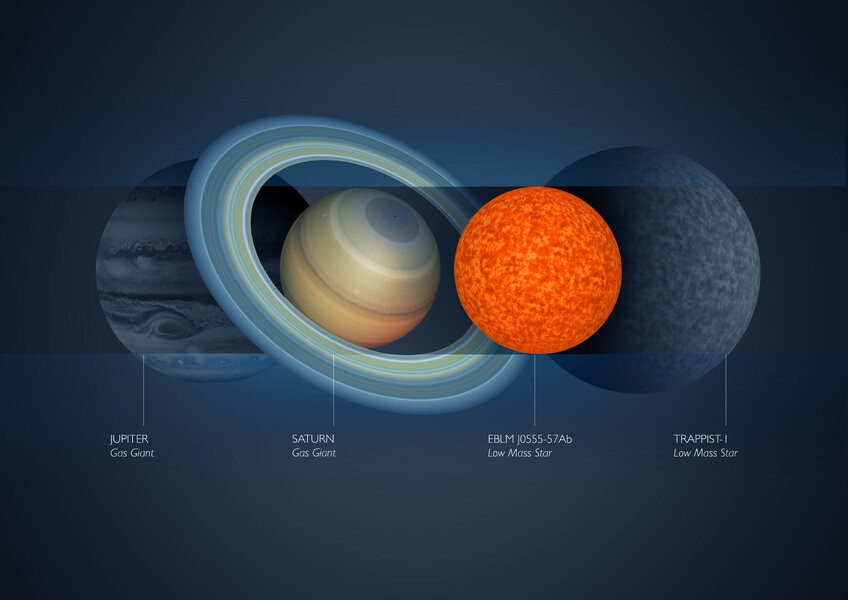

A couple of stars were recently discovered that are the smallest known. One is called EBLM J0555-57Ab, and the other is 2MASS J05233822-1403022. If the conclusions based on the observations are correct, both are just barely massive enough to fuse hydrogen into helium in their cores — it takes roughly 0.077 times the Sun's mass to do that, or about 75 times the mass of Jupiter. Both these stars are just over that limit, as far as we can tell.

So they're true stars, but they're small. Both are smaller than Jupiter, and EBLM J0555-57Ab is only about the size of Saturn!

Therefore right away we see that stars can be have planets bigger than they are.

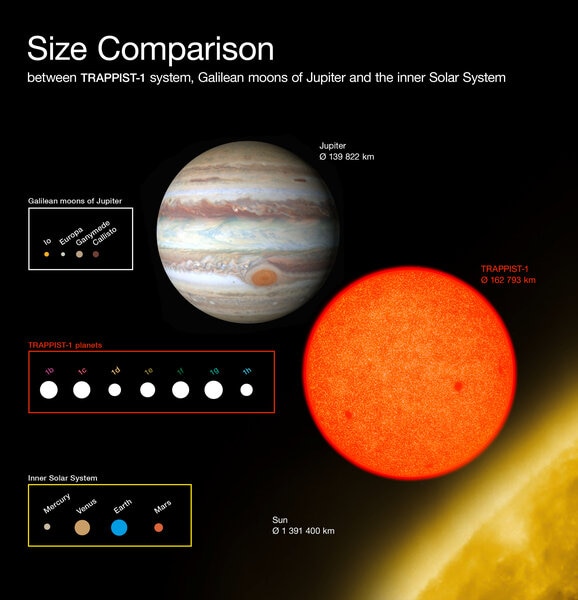

Theoretically. In practice it's certainly at best very rare. We've observed enough exoplanets — worlds orbiting other stars — to see lots of trends in size, mass, and so on. One thing that stands out in the data is that red dwarfs tend not to have gas giants orbiting them. Some do, but they usually have smaller planets, ones more like Earth (what we call terrestrial planets). Some have many like that, such as TRAPPIST-1, which has seven Earth-sized planets orbiting it.

Gas giants around red dwarfs are rare; maybe one in a hundred small stars have giant planets (Note: To be fair that survey was done with candidate exoplanets, ones that have not yet been confirmed… but looking at the list of known giant exoplanets around low-mass stars, the numbers are indeed very low, statistically speaking).

And it may get worse. The smallest stars are also the dimmest, meaning they're extremely hard to detect. That also makes it hard to know if they have planets orbiting them. We don't know if they're good at making planets at all, let alone giants versus terrestrial ones. If the trend seen so far continues, it's even less likely for these extremely dim bulbs to have gas giant planets than it is for the somewhat larger (really, less small) red dwarfs.

So it's possible that such a system where the planet is bigger than the star exists, but they're statistically very rare.

On the other hand, red dwarfs are the most common kind of star in the galaxy by far, making up something like 70% of all stars. So even though really small red dwarfs are rare, there are still many billions of them in the galaxy. If the fraction of them that has a gas giant orbiting them is small, that could still mean a lot of such systems exist in total.

So there you go. A rare actual answer in astronomy: Yes, a planet can be bigger than its star!

It's a weird Universe. That does make it more interesting, though.

[My thanks to my friend Dr. Jessie Christensen for her help with the exoplanet database.]