Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Crash Course Astronomy: Galaxies, Part II

Can a sequel be better than the original? When it comes to Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, yes.

And when it comes to an episode of Crash Course Astronomy about galaxies, then judge for yourself:

In this second part I go over active galaxies—ones pouring out huge amounts of energy, making them so extremely bright they can be seen for billions of light-years. For several years I worked on the NASA education and public outreach programs for astronomical satellites like Swift, Fermi, NuSTAR, and others that observe such galaxies. It was a grand time spent learning about these awesome monsters, following along with the cutting-edge research that analyzed how active galaxies behave and why they act the way they do. Visiting them again here for this episode was fun.

Incidentally, while “Milkomeda” is easy to say and is a structurally legitimate portmanteau of “Milky Way” and “Andromeda,” it’s clunky and awful. If you have a better name (“Andromeway” is way worse), leave it in the video comments!

As for the last bit of the video …

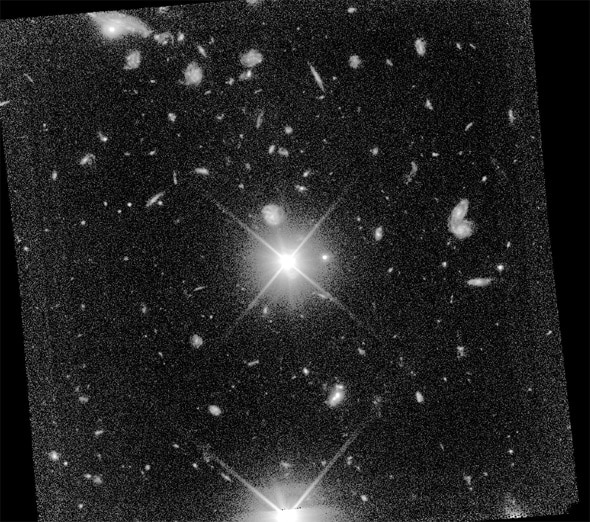

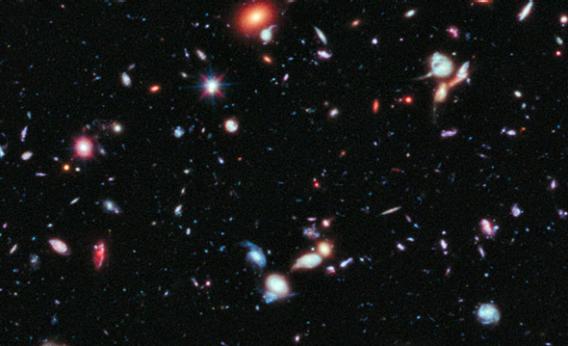

I’ve spent a lot of time pondering the Hubble Deep Field and its follow-ups. The Ultra Deep Field was taken in 2004, and the Extreme Deep Field in 2012 (a portion of which is shown at the top of this post). I am not a cosmologist, and I didn’t work directly on the science of the images, but it so happens that I did some work on one of them: the Hubble Deep Field South (or HDFS), taken in 1998.

Work? More like play. At that time I was part of a team that built, calibrated, and observed with a Hubble camera named STIS, the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph. My job was understanding how all the various components of the fiendishly complex camera worked, and worked together. It was daunting, since STIS was one of the most complicated astronomical machines ever put into space, with many dozens of components.

But every now and again I got a chance to simply play with the data. When the HDFS came in, I started fooling around with it. I took the images and added them all together in different ways to see if I could bring out different features, or suppress noisy bits that were distracting from the science.

Mind you, the visible light image was incredibly deep, a total of more than 150,000 seconds (more than 40 hours!) taken by a telescope in space equipped with what was the most sensitive camera ever launched at the time. The stacked image was littered with galaxies, fuzzy and small and everywhere.

In the images I found a galaxy that was barely more than a fuzzy spot, the very faintest one I could reliably spot. I added up the light it emitted and ran the math. I calculated that the galaxy was at a visible magnitude of about 31.

I remember the hair on the back of my neck standing up when I got that result. The magnitude scale is a way astronomers measure relative brightness of objects; the faintest star you can see is magnitude 6. This galaxy was 25 magnitudes fainter, a factor of 10 billion.

The faintest star you can see with your eye was 10 billion times brighter than this galaxy. An entire galaxy made of billions of stars.

For a moment, just a single moment, the vast gulfs in the Universe were dropped squarely into my brain. My imagination stretched, and stretched again, and I got a glimpse of the immensity of the reality we live in.

It’s a piece of my life I’ll never forget, and one for which I am extremely grateful. It’s one of the reasons I wanted to do Crash Course, and why I write this blog: I want very much to be able to share even a small taste of that experience with everyone. I hope that the last few minutes of the episode here allowed that.