Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Downtown Sagittarius is a busy place

If you’ve been following my blog for any length of time (well, more than a few weeks) then you may notice that I post lots of Hubble Space Telescope images of galaxies, nebulae, clusters, and more. I’m biased; I worked on Hubble for a long time and it means a lot to me.

But also, I’m human, and my but those images are nice.

However I recently stumbled on one that is a little bit different. No sprawling galaxy, no wispy filaments of ruddy glowing hydrogen gas.

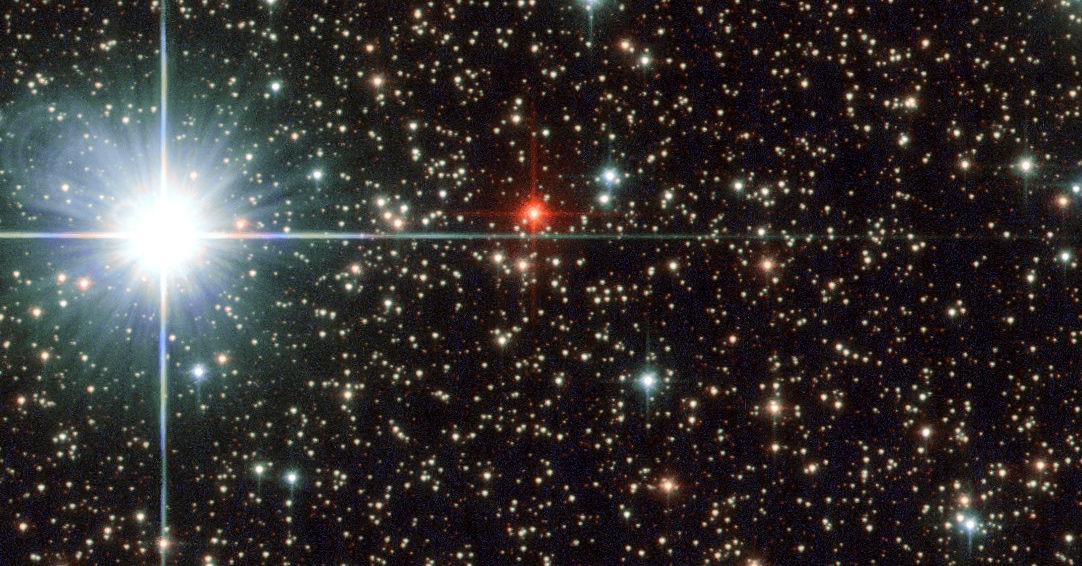

Nope. Just… stars. Lots and lots of stars.

Oof. That’s a lot of stars!

As the press release says, this is a region of the sky in Sagittarius, not too far from the center of our galaxy. That’s like looking downtown into a busy city, where all the lights are. In this case, the lights in the sky are stars*.

The filters used mimic a natural color image (with green being green and blue blue), but what you see as red in the image is actually near infrared, just outside what our eyes can see. But close enough; the stars you see here really are very close to the colors displayed, from brilliant blue to ominously ruby red.

I wondered where exactly this part of the sky was — is it very close to the center of the galaxy, or just nearby? Happily the press release also lists the coordinates on the sky (what we call Right Ascension and declination, like longitude and latitude on the sky) so I was able to cut-n-paste them into SIMBAD, an astronomical database server. Zooming out a bit, I noticed a fuzzy blob not far from this observation, and immediately had a suspicion what I was seeing.

So then I put the coordinates into the Hubble database, and boom! I found the observations. The blob next to the observation is a globular cluster called Terzan 5, which may actually be the cannibalized corpse of a smaller galaxy our Milky Way ate… and it turns out that was why these observations were made.

Terzan 5 has a whole passel of weird celestial beasts in it called millisecond pulsars. A pulsar is a neutron star, the extremely dense core of a massive star that previously blew up as a supernova. Neutron stars are so dense the only thing denser is a black hole, so as you might expect they have some unusual and soul-crushing properties.

One of these properties is a fiercely strong magnetic field. Neutron stars also spin rapidly, sometimes in less than a second… and mind you, this is an object about 10 kilometers across but has the mass of our Sun. There’s a lot of energy locked up in its spin, and that makes the magnetic field incredibly strong. The details are a tad bit complicated, but energy screams away along the magnetic field axis, tightly focused into a pair of beams, one for each magnetic pole. If those beams pass over the Earth we see a blip of emission every rotation. The star seems to pulse, hence the name.

But some pulsars orbit normal stars like the Sun. If they’re close enough, material from the star can get pulled onto the neutron star by its ridiculous gravity. This winds up making the neutron star spin even faster. Some of them turn into pulsars that can rotate hundreds of times per second — the fastest one known spins at a rate of an incredible 716 times per second! That’s almost once per millisecond, so we call these millisecond pulsars.

Terzan 5 has a stunning 37 of these terrifying objects in it, the most known for any cluster. The purpose of the Hubble observation was to look as deeply as possible at some of these pulsars to see if the companion star can be seen (the pulsars are generally discovered using radio telescopes, which are relatively insensitive to regular old stars). That way more insight can be gleaned into what caused the neutron stars to spin so quickly.

Other science can result from this observation as well, including seeing how much cosmic dust is between us and Terzan 5 (it’s known that there’s a lot, and you can even see its effects on the cluster), what kinds of stars there are in the cluster, and more.

… but sometimes — really most of the time, when it comes to Hubble — what is motivated by science achieves the status of beauty. There is fine science to be mined by this image for sure, but just as certainly there is fine art.

*For you Fredric Brown fans.