Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

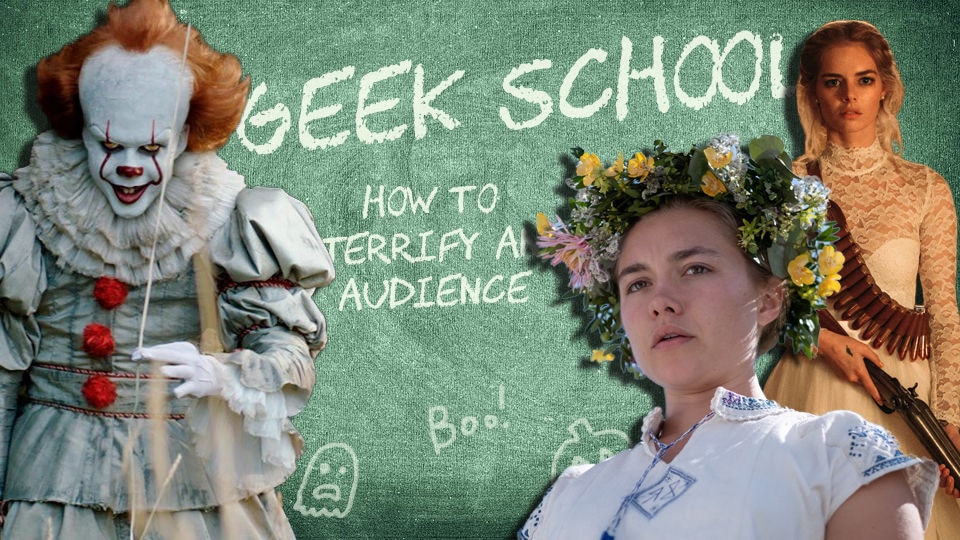

How to terrify an audience, according some of horror's biggest names

Welcome to Geek School! This SYFY WIRE series will provide practical lessons in writing, producing, and selling the nerdy projects of your dreams, with advice from some of the top creators and professionals in the business. In this lesson, we're talking about all the best ways to scare your audience.

The horror genre stretches far and wide, in part because what might scare one person doesn't faze another; while a stomach-lurching slasher film may do one person in, a straightforward ghost story will send chills down another's spine.

Yes, horror movies have garnered more mainstream attention in recent years — with hits such as Get Out, A Quiet Place, and the It films dominating the box office — but many of the tactics they're using to get audiences to jump in their seats are tried and true, perfected over generations of scares on the page and screen. Here's the advice a few modern horror greats have for anybody out there looking to get spooky.

BUILD THE TENSION

Cheap jump scares rarely stick. Sure, your heart leaps in your chest for a moment, and you might screech or even laugh in shock, but then you're on to the next thing; you're less likely to lie awake at night and consider the possibilities of what's hiding in the shadows.

Seth Grahame-Smith, an executive producer on It Chapter Two and author of such horror novels as Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter and Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, says that in his mind, horror auteur James Wan has perfected the jump scare because his films earn them. To put it simply, "It's misdirecting people, building tension, and torturing people with anticipation," Grahame-Smith says.

"He'll build tension and then give you the 'No, just kidding,' and then really hammer you with the 'No, we weren't kidding, it was a real scare,'" he explains. "It's the old 'black cat jumping off the dresser' thing where you walk into the room and you can hear somebody rifling around in the room and you build the tension and you walk toward the closet and you just know there's something in the closet. You open the closet and a cat jumps out. And you let the breath out and as soon as you turn around, there's the psycho — right in your face."

For Haunt co-writers and co-directors Scott Beck and Bryan Wood, also known for their work as screenwriters on A Quiet Place, the slow burn is essential. Haunt is about a group of students who wind up in a haunted maze that they slowly realize is more than just a series of old-school pranks and scares.

"We wanted [Haunt] stylistically to kind of slowly bring you into the dread," Beck says. "It should almost feel like a poppy — I hate to use the word 'CW' — but it should almost feel like the movie's going to be a little lighter and a little less edgier than you might expect. A little more conservative, if you will, until it kind of gets deeper and deeper and you start imagining the horror."

So misdirect, and then strike. For Ready or Not co-director Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, this means throwing conventions on their heads. "Maybe you're expecting a scare and you don't get one," he says. "Or something that normally would just be scary is actually kind of funny. However we can play with things, even in the most subtle way, is always really interesting."

His Ready or Not co-director Tyler Gillett adds that the best scares are less about truly scaring people "and more about just sort of shocking their senses."

Gillett continues: "Crafting the mechanics of a scare, there is definitely an equation to it, and it's tried and it's true and it works, and it's a valuable thing to use when you need it."

In contrast to Ready or Not are the Ari Aster-directed films Midsommar and Hereditary, which Aster describes as having an impenetrable atmosphere he strived to maintain throughout.

"If anything I find myself on set, and especially in post-production and in preproduction, hoping to create and sustain a mood," Aster says. "So if anything, it's that feeling of anticipation, like the dread of something coming is more important to me than the actual payoff.

"And I don't like jump scares. I feel like both films have moments that are inadvertently serving as jump scares, and I'm okay with those because they happen, because that's just what the moment requires, as opposed to me looking for opportunities to do them."

FIND THE CORE BEYOND THE GORE

"We think that for something to be genuinely scary, for you to leave a scene or leave a movie feeling like, 'Holy s***, I just watched something genuinely terrifying,' it has to go deeper. It has to go beyond just that sort of immediate sensory reaction to something," Gillett says. "It has to be emotional. And that's why the end of the movie Se7en is such a touchstone in the genre world, because you leave that movie so horrified by the architecture of what that evil plan is.

"What's genuinely scary about Ready or Not," he continues, "is the premise of this young woman thinking that she's playing a fun game, not realizing until it's way too late that these people are out there to kill her. And that just on its own, on a foundational level, is so chilling and so f***ed up."

Beck similarly says that A Quiet Place is not so much a horror movie as it is a family drama with horror elements. "It's a film that's about broken communication and trying to overcome that," he clarifies.

So sometimes, finding an emotional core means taking advice from other genres — all of which results in horror's multitude of subgenres.

"What kind of feeling do you want people to leave the theater with?" Gillett says. "What were you shooting for on this one?"

CHARACTER STUDY

For a scare to come from a place of emotion, frankly, it helps if the audience actually likes your characters. Sure, it's fun to watch bad, unlikable folks get what's coming to them onscreen, but the stuff that sticks with an audience will be watching a beloved or simply relatable character kill or be killed.

That was certainly the case in Ready or Not, in which the main character, Grace (Samara Weaving), is the only one you can really root for in the end. Besieged by a WASPy family hell-bent on killing her before the sun rises, Grace fights tooth and nail to escape — and you can't help but be on her side.

"It's the marriage of craft and mechanics and character. If you're not with the character, it sort of doesn't matter. If it's a loud noise you might jump, but it's not going to resonate in any way," Bettinelli-Olpin says. "For us, it might even be cliche at this point, but it's character first. And then, from there, we build the mechanics of the scare around them."

In their initial meetings with Haunt producer Eli Roth, Beck and Woods recall him talking about the importance of audiences liking literally anything about the characters they're supposed to be rooting for.

"Otherwise it's meaningless when they die," Woods explains. "Nobody really talks about this when you talk about an Eli Roth movie, but most of his movies are almost 40 minutes of character, which is pretty unorthodox in the horror genre. Especially in what has been deemed kind of like the 'torture porn' version of the horror genre."

Grahame-Smith admits that translating a character's inner thoughts and feelings to the audience is certainly easier when he's writing novels.

"It's a different thing when you're writing a book, because you can craft a scare for 30 pages," he explains. "Not that I would try to sustain a scare for that long, but you know you can really get inside people's heads, and you can actually get inside the head of your lead character and experience what's going on through his or her eyes and ears."

THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS

As you shift further away from story and have fully realized characters to work with, that's when you can get into the nitty-gritty. Collaboration is key at this point, as you'd likely be working with a host of behind-the-scenes creators and designers to help define the world that will terrify your audience.

But, at the end of the day, as Jeremy Slater points out, imagining all these details and such are perfectly well and fine — but translating them to real life is the challenge. For that, you need your team.

"Scares don't work on paper!" Slater, who wrote The Lazarus Effect (2015), Pet (2016), and The Exorcist television series, explains. "So my job becomes less about being succinct and more about painting the general atmosphere of the scene, to help the studio and filmmakers understand why I think this particular scene could be scary. And a lot of that involves playing with formatting and white space."

"There's no such thing as a scary screenplay. It simply doesn't exist!" he continues. "There are scripts with creepy ideas and unsettling moments, but your reader is never, ever going to be genuinely frightened by what's on the page.

"And that's because scripts themselves aren't 'art.' They're a technical blueprint designed to help a team of craftspeople create art. It's the difference between staring at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel versus studying the architectural blueprints that the builders used to assemble the chapel in the first place."

Us cinematographer Michael Gioulakis points out that audiences can build a relationship with a character simply by studying the emotions flitting across an actor's face. "I guess for me it really becomes more about subjective filmmaking, trying to immerse [the audience] and using the camera to reflect the emotional state [of the character]," he says. Getting in close and finding the right angles and lighting for every little microexpression helped Gioulakis and director Jordan Peele communicate what the family at the center of the movie were experiencing from moment to moment.

Gonzalo Amat, the director of photography on The Man in the High Castle, believes a good scare is a combination of lighting and camerawork.

"You can hide stuff with a camera, you can reveal stuff when you want it to happen, you can set up for a scare with a move with the lighting. Just by creating the timing of how the camera moves, that can create a reaction," he explains. "People react more to lighting and color than they do to the way the camera tells us something. Try to find what's in the shadows. The less you see, the more your brain kind of completes the image. The less you see, the more you complete yourself. So if you don't see the creature fully, you have your own interpretation, which is a lot scarier than seeing it in full daylight."'

But it's not all in the characters and camerawork. Sometimes the smallest details are the most disturbing.

While The Purge movies and television series might be best known for their shocking kills and jump scares, the details that have gone into the upcoming second season make a fictional world painfully realistic.

When costume designer Eulyn Colette Hufkie and her team were designing literally hundreds of masks to potentially appear in the show on Purge night, she recalls discovering that everyday objects used in odd ways were the most disturbing. Specifically, she remembers a Purge mask that consisted of gluing doorstops to the mask — something about it was deeply unsettling.

She suggests having as much fun as you can when coming up with things that are supposed to be scary. Often, the most out-there concepts will be what work.

With additional reporting by Jennifer Vineyard.