Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Wait... was that a ginormous burst of cosmic energy or just space junk?

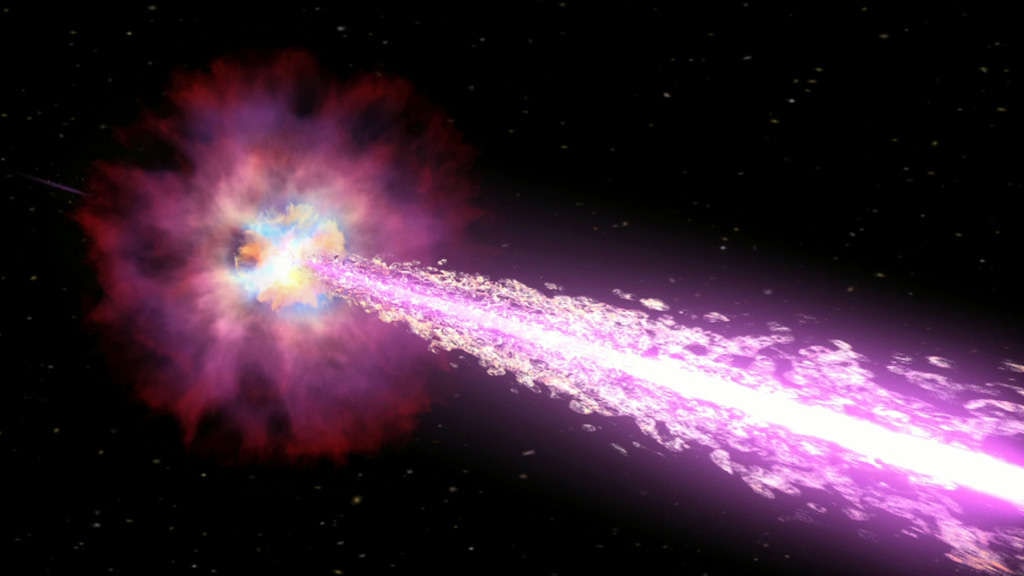

Next to supernovas and neutron star mergers, gamma ray bursts are some of the most energetic phenomena in the universe — but what if a flash of light isn’t what it seems?

There has never been a gamma ray burst observed in the Milky Way. While random gamma rays (caused by particles in cosmic rays that collide with other particles in space) are darting around all the time, no human being has ever documented an explosion of such magnitude. Not that we’re missing out on anything. Gamma ray bursts may have occurred before our species even existed. Even worse, they might have even led to several mass extinctions.

When a team of researchers using the Mauna Kea Telescope in Hawaii eyed an intense flash last year, they ruled out other causes and came to the conclusion it could be nothing else but a gamma ray burst (GRB). It was supposedly coming from the galaxy GN-z11. At 13.4 billion light years away, it is the furthest galaxy ever observed. The same researchers were soon challenged by another team thinking it was space junk, but continued to insist that they actually saw a GRB.

Now another team has a vastly different explanation for that fleeting brightness. Krzysztof Kamiński and his colleagues from the Astronomical Observatory Institute at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poland are proposing it really was light reflected by space junk. They recently published a study in Nature Astronomy.

“It is very unlikely that a GRB will be detected when observing through the very narrow slit of a telescope,” Kamiński tells SYFY WIRE. “That drastically reduces its field of view. GRBs are typically detected when using dedicated, very wide field of view instruments.”

Space junk continues to be a growing problem as more and more rockets are launched out of the atmosphere and shed their upper stages. It also doesn’t help much with the light pollution that is already plaguing astronomers everywhere on the planet. Rockets and the metal trash they leave behind are actually bright enough to be observed by most telescopes, even those whose vision may not be that phenomenal. The GN-z11 flash was relatively dim because you’re not exactly going to see an explosion as more than a blip in the sky from that far away.

So why was something barely visible mistaken for a GRB? As he previously mentioned, Kamiński thinks this was probably because telescopes observe things through a narrow slit. A public space-track website revealed there actually was a rocket that shrugged off its upper stages around the same time the observation thought to be a GRB was made. Something as bright as a hunk of rocket orbiting Earth is going to get the attention of a scope if it crosses the part of the sky being watched.

The junk metal was moving so fast that it flashed at a speed and brightness easily mistaken for a GRB. If that was a GRB, it would have been a monumental find, and not only because none have been seen in our galaxy. They are so rare that one is unlikely to be caught twice in one galaxy during a human lifetime. Entire civilizations have risen and fallen between GRBs.

“On average, we would need to wait for several hundreds of thousands of years to observe one GRB in a galaxy,” Kamiński says. “We have observed only three supernovas in our galaxy during the last 1,000 years. GRBs are much less frequent, so our chances are still very low.”

We still need to figure out what to do with all the scrap metal that serves no purpose except clogging up our view of the sky. Debris can get in the way of actual objects and occurrences. For now, the only thing Kamiński believes we can do to improve observations is to keep track of space junk and other man-made objects while continuing to improve the vision of telescopes, so they can separate both garbage and satellites from everything else out there.

“We need high accuracy and complete space debris catalogues,” he says. “Because there seem to be no technical solutions on the horizon.”