Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

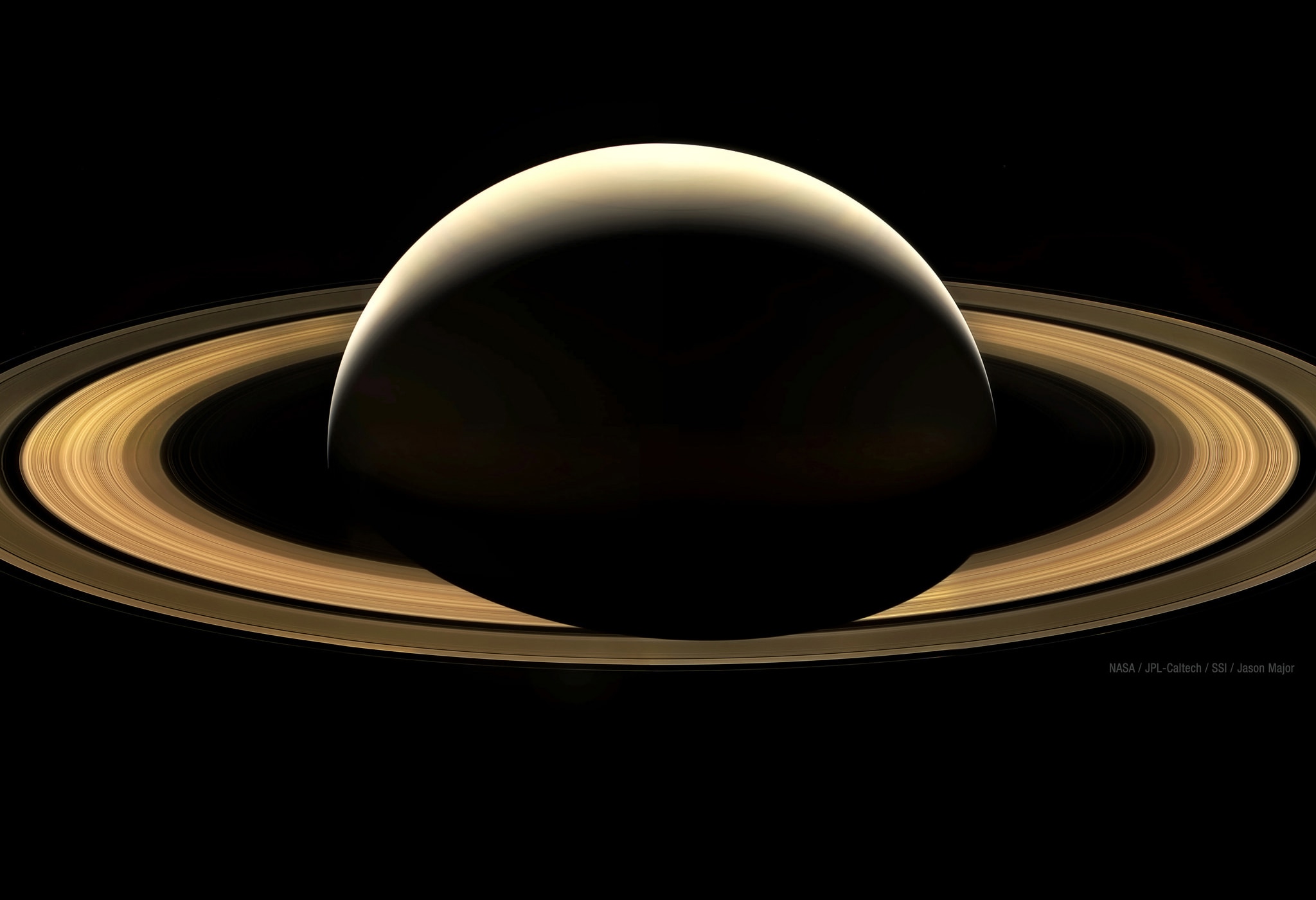

Good night, Saturn

Not long ago — a few nights after the solar eclipse, in fact — I was looking at Saturn.

I was in rural Wyoming, and the sky was a bit hazy, but it was the brightest object in that part of the sky. It looked a bit funny hanging there, the stars in Scorpius appearing to curve around it as if nestling the planet. But those stars were hundreds of thousands of times farther away from me, toward the bustling center of our galaxy, and have no claims nor cares about objects in our provincial solar system.

We do. But of course, we live here. We’re biased. Still, Saturn is an object of rare beauty, and as I looked at it that night I wondered if alien stars had their own version of our solar system’s crown jewel: Exoplanets with trillions of tiny icy particles forming annuli sprawling across their sky, a fleet of weird and wondrous moons circling near those rings, each carving gravitational calligraphy in their wake.

Maybe. Maybe even probably. But Saturn is our own and, that night, it was my job to show it to other people.

I had my telescope set up in a field, and a couple of dozen people standing in the increasingly chilly mountain air waiting to see the planet. Spirits were still high from the amazing astronomical event we had, as a group, witnessed earlier that week, and most had already had a go. But a handful of folks still hadn’t seen, and, in a couple of cases, this would be their first time even gazing upon Saturn through a telescope.

I live for these moments. I adjust the eyepiece, making sure the planet is centered and focused. Then, I back away from the telescope and tell the first person in line to take a look. She crouches down a bit to look into the eyepiece, and I do what I always do: I watch her face. Because what happens next is magic.

The simultaneous gasp, smile, laugh of delight, eyes widening in disbelief. “Ohmygod,” they all say. They always say. She says. “Is that real? That’s Saturn?”

I smile back, sharing her enjoyment. “It is. And see that star to the left of it? That’s Titan, its biggest moon. It’s bigger than the planet Mercury! And you can see the gap between the planet and the rings, too.”

The amazement visibly radiates from her. Then I point out where Saturn is in the sky so she can see it for herself, and tell her that the light she sees now left Saturn over an hour ago, when we were finishing up dinner. This elicits another little gasp from her, her brain taking all this in.

Watching this is like drinking joy. Being a part of it is a gift.

And knowing all this, knowing Saturn is real, it’s out there, an entire world that was up until extremely recently just a point of light in the sky, so very distant and yet so very reachable — that is truly an astonishing capability.

We humans have only understood this for a very short time. And for a shorter time yet, we’ve been there. To Saturn. At Saturn.

We’ve seen Saturn up close, and with very different eyes. Yes, a camera designed to more or less reproduce what our eyes see, but also equipped to scrutinize light from the planet in a hundred different ways. And also to chew on the dust around it, sniff the gas in its environment, sense the beating heart of the planet’s powerful magnetic field.

No human has been to Saturn, but our robotic proxies have been, and in this latest case, its senses are so much more exquisite than ours. We have not just seen Saturn, but through this distant explorer, we’ve felt it, experienced it, found ourselves baffled by it and still understanding it better than any humans in history. In the past 13 years we’ve learned as much about this ringed world than in all the years before. Perhaps more.

We’ve been awed by the photos and animations showing moons in motion, rings sweeping around, atmospheric storms erupting, exhibitions both sublime and gaudy. Geysers of water, dunes of hydrocarbons, wide girdles of snow, moons polluting one another, weather patterns changing with seasons, huge wakes of material bobbing up and down as well as in and out as tiny worldlets pass by.

Wonders to satiate any brain, no matter how inured by the mundanities of everyday reality. Yet these wonders do happen every day, on and above this extraordinary planet.

They will be studied with bliss and exhilaration and relentless determination by scientists across our own planet for decades to come. More insight will be teased from these observations, some ever more subtle and incremental, some creating a gestalt as multiple phenomena are assembled into bigger conclusions via a framework of science.

And our understanding will grow. This is the gift of our Saturnian traveler. To increase our knowledge and broaden our grasp while giving us ever more reason to delight in the overwhelming beauty of a world hundreds of times more voluminous than our own.

From now on, when I stand in my yard, or in some other state, or anywhere on this blue-green world, and my own gaze falls upon that yellow unblinking light in the sky, I know a smile will slip onto my lips. Because I know Saturn better now than I ever have, and that the same is true for so many others like me, like you, like everyone who chooses to wonder, everywhere on Earth.

And for that, for that, I thank you. Farewell, Cassini. You’ve made two worlds better places to be.

The image shown above is a mosaic composed of some of the very last images Cassini ever took of Saturn, on September 13, 2017. They were processed and assembled by graphic designer Jason Major (with credit to NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute).