Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

How Titan's deepest sea can give us a glimpse into what Earth was like billions of years ago

Because there was no one around with a camera back then, we will never have a real-life documentary special on what Earth was when it was still a primordial soup swarming with bacteria. What we do have is Titan.

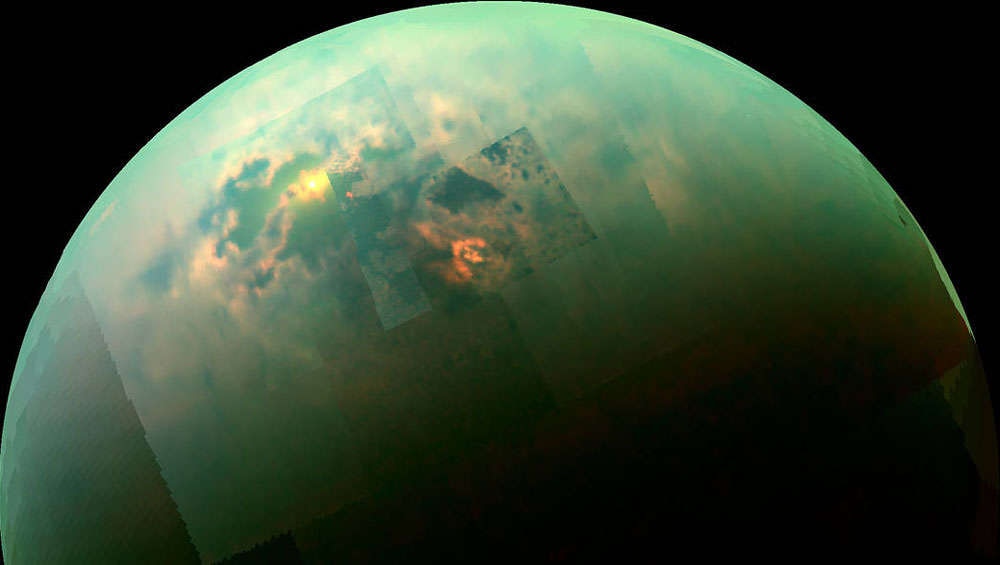

Saturn’s largest moon is a no man’s land. Whether anything can survive in this subfreezing place, where it rains methane and ethane all the time, is debatable. Looking at the cesspool of poisons that is Titan makes us almost forget that Earth was pretty noxious itself if you go back far enough. It could even be something of at time-warped mirror universe. The organic haze in Titan’s dense atmosphere is thought to be extremely similar to early Earth’s, and it is the only known world besides Earth to have liquid rivers, lakes and seas on its surface, even if they are toxic.

Do the eerie similarities between Titan and Earth mean Titan could be at the stage of evolution our planet was at several billion years ago, and even still evolving? Maybe.

“Titan is important because it represents a reference planetary environment for studying the role of liquid water in chemical evolution, since organic chemistry on Titan has been occurring 4.5 billion years in absence of water,” Valerio Poggiali, who recently published a study revealing new findings about its deepest sea, Kraken Mare, in the Journal of Geophysical Research, told SYFY WIRE.

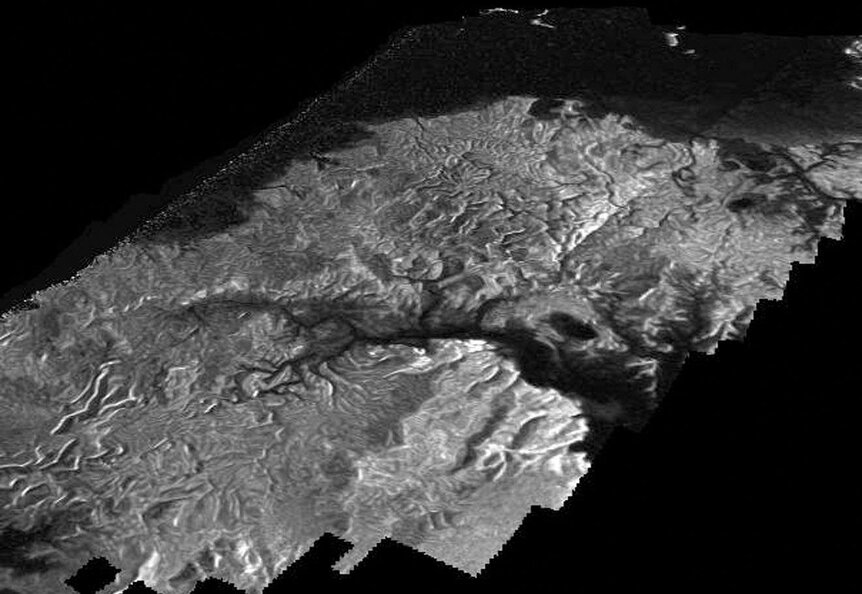

Plunging into Kraken Mare (above, at the left of Titan’s north pole) could be one way of finding out things about Titan that relate to what nascent Earth is believed to have been like. Both bodies have atmospheres that are mainly nitrogen, though the methane in Titan’s makes it unbreathable to humans. Earth also had some methane in its atmosphere once upon a time. Besides its bodies of liquid hydrocarbons that appear similar to Earth’s rivers and lakes, Titan is also the only place in the solar system where rain actually happens. Methane and ethane will evaporate into the clouds and condense before raining down on its frozen crust again. Cassini first saw through the haze to make out bodies of liquid that looked remarkably Earth-like.

Cassini could not get all the way to the bottom of Kraken Mare’s eldritch depths. Its radar was just not able to reach all the way, which is why Poggiali believes future missions that explore Kraken Mare should be equipped with radar that is able to penetrate deeper into the murk. This vast sea has now been found to be at least 1,000 feet deep and could rival all five Great Lakes together. Observations showed its methane-dominated “waters” are made of the same stuff as surrounding seas such as Ligeia Mare but different from further lakes.

This could be invaluable to getting more insight on Titan’s hydrologic system — processes such as precipitation, the flow surface liquid and evaporation—which isn’t too much unlike ours.

“Precipitation could drive liquid from Ligeia to the south of Kraken, where warmer temperatures cause a loss of methane by evaporation that eventually concentrates the less volatile ethane,” Poggiali explained. “The only recognized process that would act as counterbalance and avoid the total saturation in ethane of Kraken Mare would be the tides, which must cause a strong remix of liquids against the precipitation flow.”

The most methane on Titan, as suggested by recent computer models, is most likely in the far north where Kraken Mare and Ligeia Mare are located. Figuring out the chemical compositions of the moon’s bodies of liquid methane and ethane can tell us more about its hydrologic processes and how they work on Titan versus Earth. How solar heating or wind stress affects seas circulating across Titan could also give a better understanding as to how they rise, fall and flow, possibly in a similar way those on our planet have been for eons.

There are still things that the haze shrouding Titan continues to hide. How all that liquid methane that floods the seas of Titan originated remains unknown, even though it constantly rains down on those seas. Another mystery is how methane still hangs around in Titan’s atmosphere when UV rays are always breaking the methane molecules apart. There has to be extra somewhere, or at least Poggiali suspects there should be.

“I think the answer is in Titan's interior,” he said. “Methane and ethane could be entrapped in crustal clathrate ices, or a larger than expected quantity of sand made of heavier hydrocarbons is being produced.”

When NASA’s Dragonfly quadcopter touches down on Titan, or a space submarine dives into Kraken Mare, it might finally demystify what is really going on out there — and possibly offer us the closest thing to a vision of Earth’s distant past.