Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

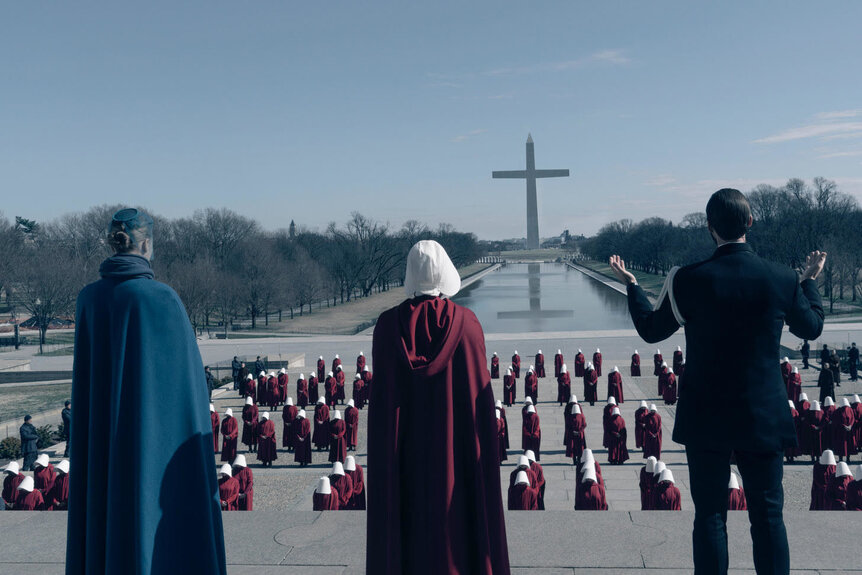

How to create a dystopia, with help from the Handmaid's Tale team

Welcome to Geek School! This new series will provide practical lessons in writing, producing, and selling the nerdy projects of your dreams, with advice from some of the top creators and professionals in the business. In this lesson, we're talking about creating dystopias.

If we don't pay heed, X could happen, or Y, or Z. We could lose the right to read. Children might be compelled to fight each other to the death. A tyrannical dictator might come to power. Artificial intelligence could decide to eliminate us puny humans. The whole earth could become inhospitable to life. Whatever the scenario, dystopias work best as cautionary tales — rooted in the present, then extrapolated to extremes. The Handmaid's Tale imagines a theocratic regime taking away women's rights — given the current state of affairs in certain parts of the world, some think the story should be filed under current events, not speculative fiction.

If you want to create your own eerily prescient projection of a future in which everything has gone wrong, you'll need to get a few things right. SYFY WIRE spoke to several people who make The Handmaid's Tale, including the showrunner, directors, and writers, to learn from the best when it comes to making things the worst.

DECIDING WHICH SUBGENRE

What kind of oppression do you want? Is yours a reality-based world or an alternate history, with an authoritarian, theocratic, or military government? Or has the civilization in your world been shaken by an environmental disaster, an apocalyptic event, or some sort of supernatural calamity?

"It's a really massive question," says director Daina Reid. A lover of speculative fiction, she can rattle off all the various kinds of dystopia, from the political (Nineteen Eighty-Four, Brave New World, Fahrenheit 451, Battle Royale, The Hunger Games, The Purge) to the economic (Player Piano, Oryx and Crake, RoboCop, Rollerball, Snowpiercer), the technological (The Matrix, The Terminator, Westworld, eXistenZ), the metaphysical (The Good Place, The Leftovers), the environmental (WALL-E), and combinations thereof. "Try to find the normal, and then undermine it and destroy it," she explains.

Once you determine the genre subclass, you can figure out geography and time period. Because Gilead takes place in the near future, it provides a mirror to what's happening now and what could happen later. "It's a near enough future that it doesn't look like fantasy," director Kari Skogland says. "It's just within our grasp, but within our fear."

"A zombie dystopia like The Walking Dead is very different than Gilead in The Handmaid's Tale," Reid says. "There is a beautiful aesthetic in Gilead. You almost go, 'I want that house,' even though what happens inside the house is really horrible."

DETERMINING A POV

With The Handmaid's Tale, the point of view is right there in the title. "In Gilead, the world is having fertility issues," Skogland says. "And the Handmaids are the next way to save it … or not."

"You get to experience the world as they do," writer Kira Snyder adds. "And it's a way for the audience to not be too far ahead of the character."

If there are rules to establish in your dystopia — sex is not allowed, or is allowed but only in certain circumstances, or is allowed but monogamy is not — then we should be with the characters as they discover the rules.

"With Katniss in The Hunger Games, we're in her world from the beginning," Snyder says. "We're not getting a whole lot of third-person omniscient experiences. I think it has more impact when you are with your main character, in their point of view."

In The Handmaid's Tale, that character is June, who is severely limited in what she can express. But even when she is quiet, "June is not dead inside," says showrunner Bruce Miller. "She is still a human being. She has feelings. She has opinions. She has intelligence. So I want to make her a full person, and a full person looks around Gilead and goes, 'Oh god, what a nightmare,' – but also, 'Really?' Because it's so absurd. 'Seriously? They're going to hit me with a cattle prod every time I open my mouth?'"

Giving us access to June's innermost thoughts — the things she thinks but cannot say out loud — allows us to relate to her and demonstrate "she's one of us," Miller explains. The stranger the dystopia, the more relatable the character needs to be.

KEEPING IT REAL …

Everything that happens in The Handmaid's Tale — however outrageous — is drawn from the real world. Some historical and contemporary references are mixed together, but Gilead's tyranny feels authentic because it's happened before (or is still happening now). The color-coded attire meant to segregate women by caste (red for Handmaids, blue for Wives, green for Marthas, brown for Aunts) is drawn from several sources, including the Third Reich's yellow stars for Jews and pink triangles for gays, and Canada's assigned colors for prisoners of war. A new regime suddenly requiring women to cover up? That happened to the women of Iran during the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Gilead's practice of forced fertility and giving stolen children to high-ranking officials is derived from the actual practices under tyrants like Adolf Hitler (the Lebensborn program), Nicolae Ceausescu (Decree 770), and Pol Pot (the Khmer Rouge's state-sanctioned rape), and also references the children forcibly taken from their parents in Argentina, Spain, Canada, Australia, and the United States. The ceremonies in which political dissidents are punished — the "particicution," in which a mob of Handmaids tear apart the prisoner with their bare hands — are drawn from bloody sacrificial revels in ancient Greece and gruesome depredations during the French Revolution. Saudi Arabia, Iran, Somalia, and North Korea still hold public executions, often for the same crimes for which the citizens of Gilead are punished, such as adultery and homosexuality. Unfortunately, there is no shortage of real-world cruelty for The Handmaid's Tale to draw upon.

"If you're telling a sci-fi/fantasy dystopia, you absolutely can have inventions," Snyder says. "But having anchor points in the real world makes it feel grounded. In terms of building a world that makes you think, we lean into specificity wherever we can. We're research nerds, and we like to get this stuff right. We talk to experts who try to rescue women who are being held captive by extremist networks. We talk to Human Rights Watch. We talk to the UN quite a bit."

The latter connection is series consultant and UN deputy director Andi Gitow, a cousin of showrunner Bruce Miller. He first consulted his relative during Emily's female genital mutilation storyline, and he kept the conversation going regarding aid workers, refugees, family reunifications, and the International Criminal Court. But The Handmaid's Tale isn't a documentary — these anchoring elements are driven by the story.

"With Emily, it didn't start with female genital mutilation," Snyder explains. "It started with us thinking about how Gilead would punish her for the sin of loving a woman. They can put her lover, the Martha, to death. But Emily is valuable — she's a fertile woman. They want more babies from her. So what would Gilead do? And what happens in the real world is FGM."

When they shot the FGM reveal in Season 1, director Reed Morano instructed actress Alexis Bledel not to get angry until the end of the episode, and not to get angry directly at Aunt Lydia, who was responsible. Says Morano, "You could either end this episode feeling bad for Emily and be like, 'Oh, look at this pathetic Handmaid crying,' or you can end this episode like, 'I am scared she is going to f*** some s*** up.' Because if she's screaming, what's next?"

Emily's rage foreshadows her later rebellion, and it feels like the way we might react in that dystopia, because both we and Emily are accustomed to life in our modern world. But as we get further into the series, we encounter characters who have been raised in this dystopia and have never known another world, and they don't resist in the same way. Eden accepts her death sentence calmly. She refuses to renounce her sins and recites Bible verse as her last words.

"When we were thinking about what happens with Eden, who runs off with a young Guardian, we didn't start thinking, 'We're going to drown these two young people,'" Snyder says. "We started thinking, 'As far as Gilead is concerned, Eden and Isaac are adulterers. So what would Gilead do to them?'"

In doing their historical research, the writers came upon a feudal custom in Scotland called the drowning pool. "Back in the day, it was considered a cleaner death than hanging," Snyder says. And so Eden and Isaac are sentenced to drown together. "It's always, 'Here are the characters, here is the story, here is the world, what would happen next?' That's the guideline for the whole show. 'What would really happen?' is one of the mantras that we have for the writers' room."

… BUT NOT TOO REAL

As brutal as Gilead already is, it could be a lot worse in terms of the physical punishments drawn from the real world. The Handmaid's Tale team has pulled back from making their dystopia so violent that audiences won't be able to identify with it at all. "There are some things we do and some that we don't do, because we can't relate them to the viewers' actual experience," Snyder says. Even if we know that the penalty for some crimes in some countries today is hand removal, it still doesn't seem real to those who haven't witnessed it. So the version in Gilead is sanitized — instead of an executioner chopping off someone's hand (or in Serena Joy's case, part of a finger), it's a medical professional doing it.

"Most of us have not had our hands amputated," Snyder notes. "So the way it was conceived and filmed was like it was a hospital procedure. You'd hear the sound of the doctor firing up the bone drill and hear the movements like cutting into the flesh. That's close enough to our experience. Who hasn't sliced their finger on a knife? When Serena gets part of her finger taken off, she unwraps it and looks at the stitches, and it feels like that's something that can happen to anybody."

The audience reaction is still visceral — we still cringe — but it's not as traumatic. "If you see someone on TV get a paper cut, or get something stuck under their nail, you flinch," Snyder says. "You feel the pain because you know what that feels like. Very few of us know what it's like to have an arm lopped off, so it doesn't necessarily have the same kind of resonance." The hurt finger seems more "real" than a chopped-off limb, Snyder says, and the more "real" it seems, the scarier it is. Consider that when you decide how to utilize violence.

DEVIL IN THE DETAILS

Deciding what the subgenre is, what the story is, who the main character is — all of that goes into creating the big picture of your dystopia. But it feels more real when all the parts that serve the story start to come together on a smaller scale, too.

"We think about the macro and the micro, the general and the specific," Snyder said. "We think about the broad strokes of this world – it's Gilead, it has this caste system, it has certain tenets to its religion, which they created by cherry-picking parts of Bible scripture for their own purposes."

On top of those big pieces, the show's writers always keep in mind the smaller ones, too. For example, the places in which the written word might appear in Gilead, since this is a place where women are not allowed to read. Small details can have big implications. "We take pens for granted," Skogland says, "just like we take for granted our ability to choose, our ability to vote, our ability to have an opinion. We take it for granted — until it's not there. So the pen is a metaphor. What does having a pen and paper mean in Gilead, and how emotionally charged would it be?"

The lack of written words naturally affects signage, too. "What do the shops look like when you don't have words?" Snyder says. "What do the tokens look like when you go shopping?"

In addition, the quantity of goods in shops, in pantries, even in kitchen drawers needs to be right — not too much, but not too little, either. "We have this rule about Gilead, that there is no excess," says production designer Elisabeth Williams. If June is rummaging around looking for things she needs to survive, she needs to find something, but there can't be a lot of it. "Opening empty drawers might make sense for the story, but it doesn't serve the action," Williams said. "We have to put intelligent things in the drawers and on the shelves, and without too many words on them."

Williams creates little graphic labels for items that will be seen in a grocery store, a kitchen pantry, or a bathroom medicine cabinet, with pictures indicating what the products are. For your dystopia, consider how plentiful (or not) the food supply is, what products or goods are available, and how people acquire them, as well as other factors that can give the world a lived-in look. Take the red robes now famously associated with The Handmaid's Tale. "They're all the same base shade of red," Snyder said, "but they're all aged a bit differently. Because not everyone got their dresses at the same time."

So, if you're trying to create a fictional dystopia, look around at the real world. Things get worse from there.