Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

If this alien planet exists, it might be Earth-like. Or it might not.

Astronomers have found evidence for a planet orbiting a star that, if you squint a bit and don't clean your mirror too well, looks something like a reflection of the Earth and Sun.

I know, faint praise. But this is a pretty interesting planet. It's bigger than Earth, but orbits a star very much like the Sun at about the same distance Earth orbits the Sun, meaning it gets about the same amount of light Earth does. But we can't say too much about it just yet because we're missing a key piece of the puzzle — its mass.

If, that is, the planet exists at all.

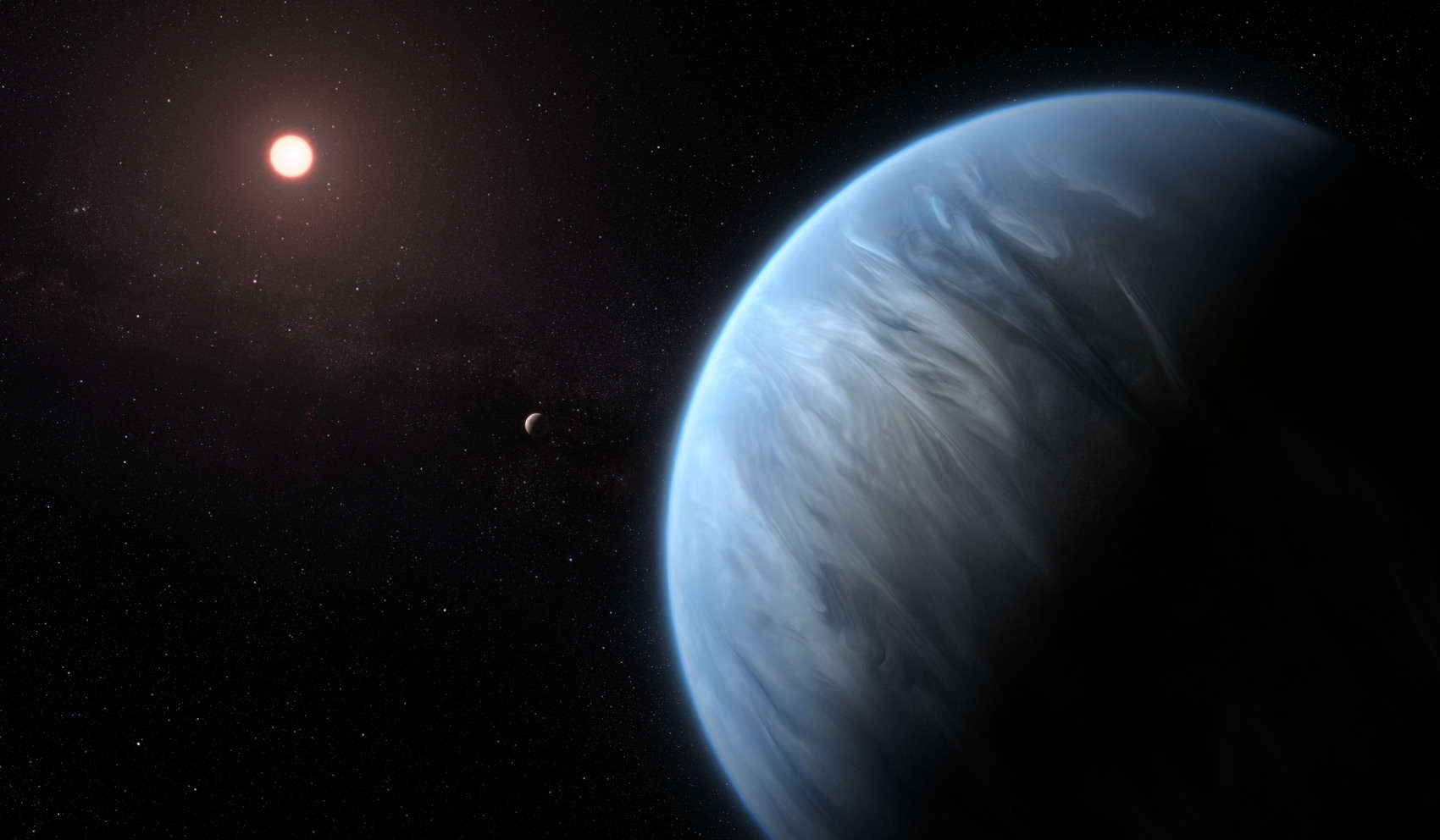

OK, so what's what here? The star is called Kepler-160, and it's located about 3,100 light years from Earth. The star is a near-twin of the Sun: It has a little less mass and is cooler, but it's also a little bit bigger than the Sun, so the amount of energy it gives off is almost exactly the same as the Sun (it's only 1% more luminous, so very very close). It's also very old, about 9 billion years, so twice the age of the Sun.

Kepler-160 is one of 150,000 stars examined by the Kepler observatory looking for exoplanets, alien worlds orbiting other stars. If we happen to see a planet's orbit edge-on, then once per orbit it passes in front of the star, creating a transit, a mini-eclipse, and the star's light drops a tiny fraction. The amount of that dip tells us the size of the planet.

Kepler-160 was found to have two transiting planets, called Kepler160-b and c*. Both are larger than Earth and orbit the star so closely they get positively cooked by it. Earth-like they are not.

Both planets were confirmed in 2014. But new measurement techniques are dreamed up all the time, so a team of astronomers re-examined the data recently to look for more planets. They found two interesting things.

One is a possible third planet found by its gravitational influence on 160c, changing the timing of its transits. It's hard to know more about this planet since it doesn't itself transit, but they estimate it has a mass somewhere between that of Earth and Saturn (about 100 times Earth's) on an orbit that's between 7 and 50 days long, so still pretty close to the star. But that's about all that can be inferred.

But it's the fourth planet that's so interesting. They found what looks very much like a series of dips in the starlight with a period of 378 days. Applying some statistics to their measurements, they find it has an 85% chance of being real; that is, not due to some instrument artifact. So they can't claim it's real — the standard is 99% confidence for a formal declaration — but the odds are good. From here on out I'll assume it's real, but just keep in mind there's a 15% chance it may not be.

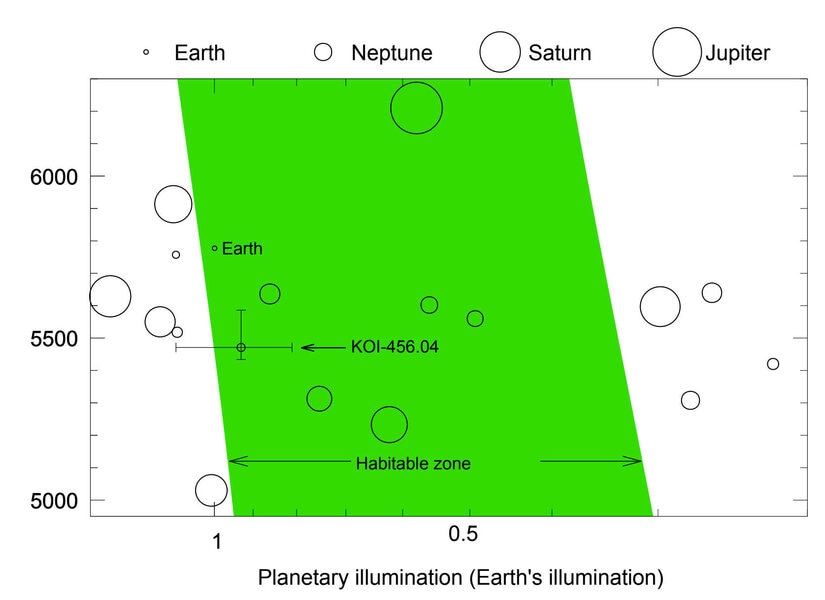

So if it exists it orbits just a skosh farther from its star than Earth is from the Sun, receiving about 93% as much energy from the star as Earth does.

But that depends on its atmosphere. Earth's average temperature without air would be about -18° C (0°F), but greenhouse gases in our atmosphere warm our average up to about 15°C (60°F). So this planet might be colder than Earth, but if it had a lot more CO2 or water vapor it could be close to our own temperature.

The problem is we have no idea what its atmosphere might be like, or if it even has one. It seems likely it will, though: The depth of the transit dip means the planet is about 1.9 times Earth's diameter, making it a super-Earth. That's about where planets start to be able to hold on to very thick atmospheres, so it could be like Earth… or it could be like Neptune. So we cannot call it Earth-like. It might be more like Venus for all we know.

This depends somewhat on the surface gravity of the planet. The astronomers estimate that if it's mostly rock and water it'll have a mass of 3.5 times Earth's, giving it a surface gravity almost exactly the same as Earth. Nifty.

But if it's metal and rock, like Earth is, the mass could be 10 – 13 times Earth's, giving it a surface gravity of 2.5 – 3.5 Earth's! That would be a bit rough. And if the planet is that dense it'll likely have a thick atmosphere. But honestly, we just don't know.

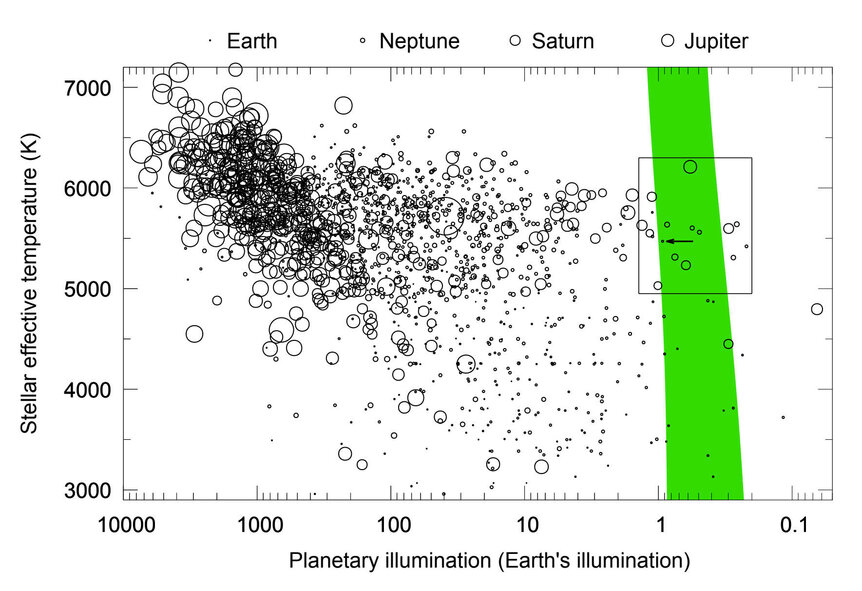

Still, the planet is in the star's so-called habitable zone (or HZ), where liquid water could exist on the planet's surface. We know of lots of planets in their stars' HZs, and a lot of these planets are close in size to Earth. But this occurs mostly for stars much smaller and dimmer than the Sun: red dwarfs. When it comes to stars more like the Sun, most known HZ planets are a lot bigger than Earth. This one orbiting Kepler-160 is by far the smallest (besides Earth, Venus, and Mars) for that stellar group. So that's kinda cool.

What has to happen next is the confirmation of this planet's existence. They predict the next transit will occur on 14 September, 2020. Hopefully some big ‘scopes can be trained on this star to look for it. The drop in starlight is only about 0.05%! So they'll have to look carefully. Finding its mass is much harder and could take years.

We're getting closer and closer to finding an Earth-sized planet orbiting a near-solar twin. That's no guarantee it'll be Earth-like, but still. The more of these we find, the better the odds are of finding another Earth. I think that's worth the search.

*The letter a is skipped to avoid confusion with multiple stars systems, which use a similar notation.