Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Is there a ghost planet hiding in the shadows behind Neptune?

At least once in your life (when Pluto was still considered a planet) you probably made a model of the solar system with wire and painted foam balls that vaguely resembled textbook mages. Nothing looked off then, right? Like a missing planet?

As much as some of us wish Pluto would reclaim its planetary status, there could have been another planet that suffered a much worse fate than being demoted — actually, more like kicked out. That's because gravity can be a beast. If this hypothetical object existed, it is thought to have been a rocky orb with a mass close to that of Mars, situated somewhere in the outer solar system. Maybe it went rogue. It could have even been destroyed.

Researchers Brett Gladman of the University of British Columbia and Nancy Volk of the University of Arizona find it highly unlikely that the only rocky planets which ever formed in the outer solar system, among its immense gas giants, were dwarf planets like Pluto and Ceres and Sedna. There had to be something more substantial out there.

“The current transneptunian population consists of both implanted and primordial objects,” Gladman and Volk said in a study recently published in Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. “The primordial (aka cold) population is a largely unaltered remnant of the population that formed in situ [and] the reason for [its] current outer edge is unexplained.”

When the solar system first started to come into being, it wasn’t nearly organized enough to display as a grade-school science project. More massive planets with greater gravitational pull pushed and shoved less massive planets around and into different orbits, which is why previous models of the early solar system have shown that it must have appeared nothing like what it does now. Some smaller bodies, like Martian moons Phobos and Deimos, are thought to have been hunks of planet blown off by a violent collision and kept in orbit by their planet’s gravity.

Something far more gruesome could have potentially happened to this planet. The early solar system — really, most of the early universe — was kind of like The Purge for any object trying to survive. Some started to form but couldn’t make it. Then there are those that were ripped apart, which is what most likely happened to the asteroid Psyche, believed to have once been the molten core of a planet that had its crust and mantle violently torn apart. NASA’s upcoming Psyche mission will further find out about the phenomena that made Psyche what it is.

If what happened to Psyche was also the doom of the hypothetical Mars that may have once tried to fit in with the gas giants in the outer reaches of the solar system, then it might now be a transneptunian object. Psyche is made of an unusual amount of metal, mostly iron and nickel. Another metal asteroid, showing up in the zone where another rocky planet is suspected to have existed, could be evidence for that planet being stripped to its core by the gravity of surrounding planets. Maybe pieces of its crust are also flying around as asteroids. No one knows.

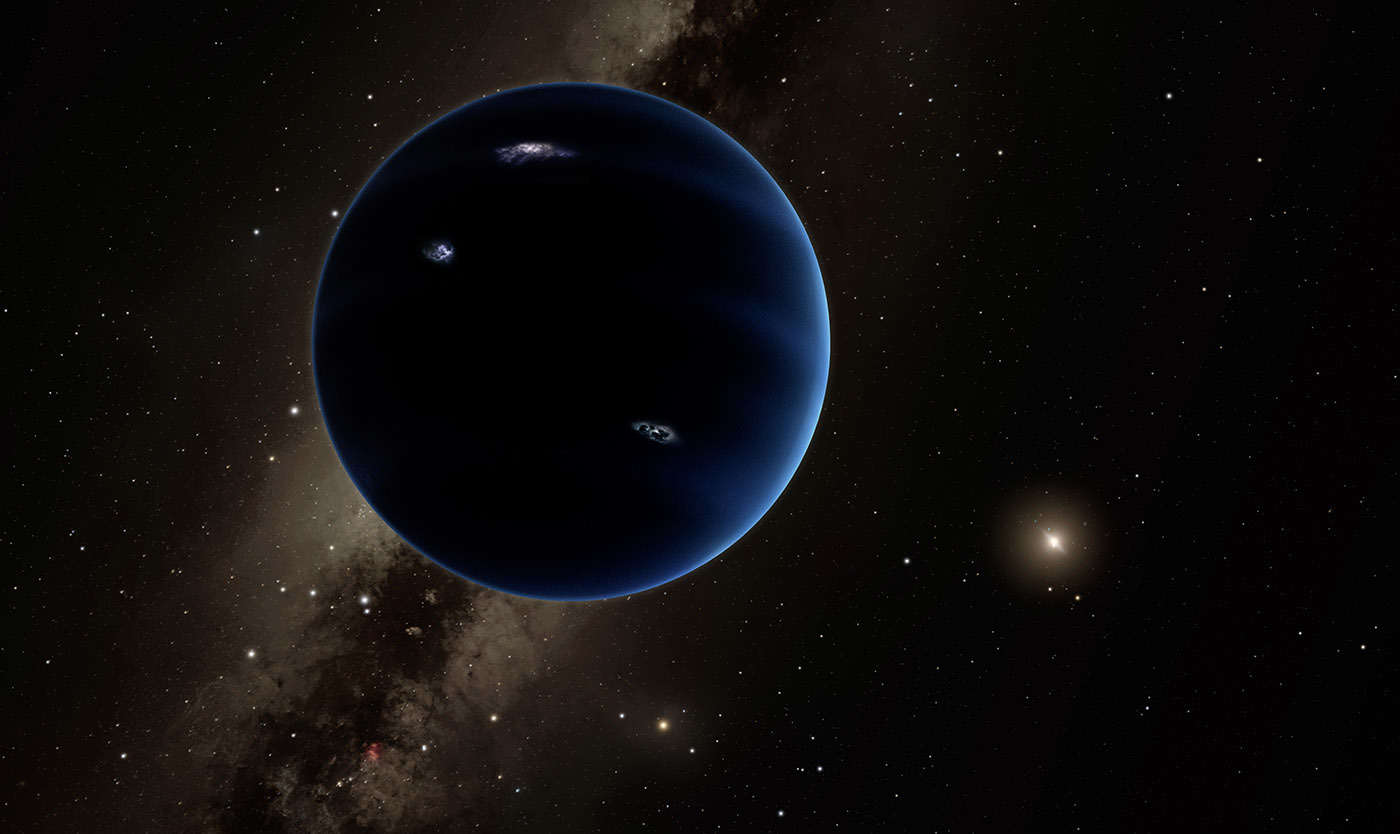

The mystery planet that either left the solar system or vanished for whatever reason is not to be confused with Planet 9. Though both might exist, or at least existed at some point, Planet 9 is viewed as an alternate hypothesis by some and an adjacent one by others. Whatever it is, it has never been seen, though more powerful telescopes might be able to find it lurking in the darkness somehow. It is thought to be much larger than the second Mars that Gladman and Volk modeled. Meaning, it could give itself away if its gravity bends starlight coming from behind.

“The large semimajor-axis population now dynamically detached from Neptune is critical for understanding the Solar System's history,” said Gladman and Volk. “[but] Observational constraints on the number and orbits of distant objects remain poor.”