Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Jaw-dropping time-lapse storm video: Vorticity 2

I lived on the east coast of the US for many years, mostly in the Washington DC area. When I moved to California in 2000, I noticed right away something weird: We didn’t get thunderstorms. Rain, yes, but never huge downpours with lightning and thunder. That area of the country has the wrong geography for them.

Then I moved to Colorado in 2007, and oh my yes do we get thunderstorms. I live just east of the Rockies, and the storms build their power right there, providing a fantastic view of towering cumulus clouds just getting their start. As the winds blow them east they gain even more strength, and can erupt as massive supercells, bringing with them torrential rain, winds, and sometimes tornadoes.

I’ve taken some photos of these clouds, fooling around with my DSLR camera. I’m an amateur, so my pictures are OK, and sometimes even good.

But I can’t hold a candle to Mike Olbinski. He’s a wedding photographer by trade, but when spring comes he transforms into a storm chaser. His photos are amazing… but his videos are staggering.

In 2016 I posted his amazing time-lapse video “Vorticity”. Just this week he released a new video, collecting footage he’s taken over the past two years, culling the best of his best sequences to create a new time-lapse, called “Vorticity 2”.

Prepare to have your brain melted. This video is incredible.

[If you can, make it 4k and full screen. The higher resolution and bigger you can see it the better.]

You may understand why he used the word vorticity! A vortex is a spinning fluid, which covers a lot of phenomena: a whirlpool, a tornado, a hurricane, even a cloud that happens to rotate. A fluid is something that can flow, so air is a fluid, and that counts here.

A lot of the storm systems you see in the video are huge supercells, tremendous thunderstorm clouds. These have what are called mesocyclones in them: Rotating structures at their base that look a lot like some alien beast descending from the skies to suck up unwary humans below. Mesocyclones rotate around a vertical axis, and sometimes can be 10 kilometers across, occupying most of the base of the thunderstorm cloud.

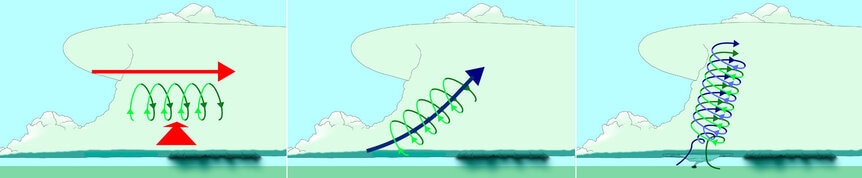

… but they don’t start that way. They actually form as horizontal cylindrical rolls of air. These occur when there’s wind shear, a change in speed of the wind with height. If the wind increases with height above the ground, for example, then air higher up is moving more rapidly than air below it. It flows over the lower air, and the friction starts the cylindrical roll.

Thunderstorm clouds are powered by convection, when warm air rises and cold air sinks. If one of these cylindrical air rolls is under such a cloud, warm updrafts lift the roll, tilting it upwards and then making it vertical. As more air is drawn in the structure grows in strength, becoming a mesocyclone.

We don’t see those where I live; we’re too close to the mountains to get that kind of wind shear over a flat horizontal plain. But east of me it’s flat and downhill all the way to Kansas, and that’s perfect for mesocyclone growth. Even better, east of here is where northerly winds carry moisture from the Gulf of Mexico up into the US, and storms like this feed on water. That’s why you get so many huge storms in the central plains.

Mesocyclones commonly create tornadoes, so that’s why that area is called Tornado Alley, the most tornado-spawningest region on the planet. In Olbinski’s video, around the five-minute mark I noticed the music getting more intense and realized I hadn’t seen tornadoes yet… and then the music really hit its stride, and the video explodes with them. It’s stunning.

There’s so much to see in the video; the aqua-green glow possibly due to hail in the clouds, mammatus clouds, lightning, microbursts, and more. It’s all amazing.

I do like to experience the occasional rollicking storm, though sometimes the violence can get a little too close. In cases like that, videos like this one will more than suffice.