Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Lethal brain surgery and possible human sacrifice exposed in unearthed Stone Age grave

Sometime between 6,550 and 6,800 years ago, two human bodies and that of a young sheep or goat were laid to rest among some of their earthly possessions in a cave on the Southern Iberian Peninsula, where they remained in the shadows along with their mysteries.

Funerary rituals are not that well known for the time period during which the people buried in the cave once lived. While rites from the Early and Late Neolithic are well known on the Iberian Peninsula, there is not nearly as much evidence on how someone was prepared for the afterlife during the Middle Neolithic. Archaeologists were able to get a rare glimpse into the past at the Deshilla Cave. Closer observation revealed evidence of head trauma and decapitation on one of the skulls. There were no jawbones on either of them. How did these people really die?

The craniums found at the site are thought to have belonged to a man and a woman (though finding that out without a pelvic bone proved to be difficult and may not necessarily be accurate). There is at least evidence for how one of them was injured, which may or may not have led to her death.

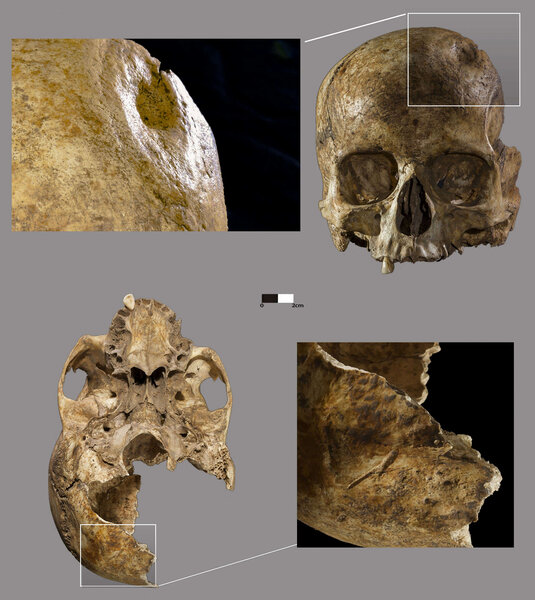

“Blunt trauma was initially considered as the cause,” said Daniel García Rivero in a study he led, which was recently published in PLOS One. “However, the absence of radiating fracture lines and the observation on the contours of the lesion of three distinct areas of smoothing may be indicative of an incomplete trepanation by scraping.”

Unfortunately, there was no such thing as neurosurgery in the Neolithic era. There wasn’t even aspirin for a headache. Trepanation, a primitive surgery that involved drilling a hole in the skull, was thought to drain fluid and relieve pressure on the brain. It also left the brain wide open to infection. While skulls have revealed survival of two and even three trepanations, the practice sometimes proved fatal from infections that would fester in the aftermath. While the procedure had not been completed on the female skull, infection was still possible. The question is why she had to be decapitated if she had indeed died of a brain infection.

Because there were signs of bone healing, this woman probably did not die immediately after the trepanation attempt, but what the evidence of regrowth cannot say is how long it took an infection to set in and possibly kill her (if that is what actually happened). The reason for what ended up being an incomplete procedure was a condition found in both skulls but more prominently in hers. Hyperostosis is excessive bone growth that is a physiological indicator of stress and also of many musculoskeletal disorders. It is possible that this was the real cause of the Neolithic woman’s demise, and possibly even the man’s, though her skull was found to have more lesions.

That still doesn't answer the question of why there was a decapitation. The bone spatula lying between the skulls was another unknown. Was it the tool used for the failed trepanation? Could that mean that the woman did indeed die from botched surgery? Also, if not the humans, had that sheep or goat been a sacrifice?

García Rivero and his team came to the conclusion that the animal must have been sacrificed, though no cut marks or tooth marks were visible on the bones, but the skull and a significant part of the skeleton were missing. It was difficult to tell whether it was a sheep or goat with what remains they had. It was probably a sheep according to one of its molars. However, the age of the creature gave insight into when the burial took place. Looking into the breeding patterns of sheep and goat species endemic to the area told the researchers that it most likely happened at the beginning of spring.

Whether the individuals who were buried at Dehesilla Cave were sacrificed remains unknown for now. It is possible that the decapitation of the woman’s skull and removal of both jawbones took place postmortem. Paleolithic skeletons found in the French cave of Grotte de Cusac display similar characteristics, suggesting that the living wanted to be close to their dead and interacted with the bones.

“This is not a common burial, such as a grave, but a complex depositional context located in the most inaccessible room of the cave and formed by two skulls without their jaws, surrounded by unusual stone structures and [grave goods],” García Rivero said. “This find is of great relevance, therefore, not only because of the scarce knowledge of the funerary practices of this period, but also because of its own singular characteristics.”