Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Mammoth find: The oldest DNA ever sequenced comes from ancient mystery mammoth

Frozen creatures seem to emerge from the permafrost of Siberia all the time, but what has made one mammoth such a huge find goes far beyond its size.

Mysterious genes that belonged to what is now known as the Krestovka mammoth have revealed more than one secret. This previously unknown species, which thundered across the icy expanse of Siberia around 1.2 million years go, breaks the record for the oldest DNA that has ever been sequenced. It also apparently had no issues with interspecies dating. It mated with of one of the stars of Ice Age, the woolly mammoth (above), which also lived in Siberia. The hybrid it spawned is actually — wait for it — the Columbian mammoth that roamed the glacial Americas until the ice melted.

“When we started doing different data analyses, we got conflicting results,” paleogeneticist Love Dalén, who coauthored a study recently published in Nature, told SYFY WIRE. “For quite some time, we thought there was something wrong with the Krestovka mammoth’s genomic data (maybe contamination). But after extensive checks and filtering steps, we started realizing that it was actually the Columbian mammoth’s genome that was odd.”

This was what actually made Dalén and his team suspicious that something else was going on there. It would have been impossible to tell that they were looking at what could be an entirely new species of mammoth from the tusks alone. Monster tusks were regular features of mammoths. If the Krestovka mammoth’s genome looked strange, it was actually the other way around. The Columbian mammoth’s DNA was found to have been merged with that of the Krestovka mammoth. Turned out that the Columbian mammoth, which first appeared about 420,000 years ago, had such a confusing genome because it was the offspring of Krestovka and woolly mammoths.

Dalén finally figured it out when he and a colleague were up late trying to figure out why something about the Columbian mammoth wasn’t making sense when the hybridization jumped out at them. The sequencing of the Krestovka mammoth’s genome was what brought them to this realization, and that in itself was something of a labyrinth. DNA degrades, even in a specimen that has been in a deep freeze for eons, and especially when that specimen has been around for a million years. Long strands break down into shorter and shorter ones that become more difficult to analyze. The same type of lab work applies to any ancient DNA specimen, but what becomes more difficult is extracting and then putting the fragments back together.

“The shorter the DNA fragments are, the more difficult it is to identify which DNA sequences are from mammoth and which are from contamination such as bacteria that have invaded the teeth, plant DNA from the sediments and human DNA from the paleontologists or us in the lab,” Dalén said.

Just to give you an idea how ancient the Krestovka mammoth’s DNA is, it is about a thousand times older than that found in most Viking remains, older than humans and the Neanderthals that predated and eventually interbred with homo sapiens. It also predates woolly and (obviously) Columbian mammoths, meaning that woolly mammoths must have evolved later while the Krestovka mammoth was still around. Never mind the hybrid. Previous studies had come to the conclusion that there had been only one species of mammoth, the steppe mammoth, in Siberia. Evidence from DNA analyses has now shown there were probably at least three: the Adycha, Chukochya and Krestovka mammoth.

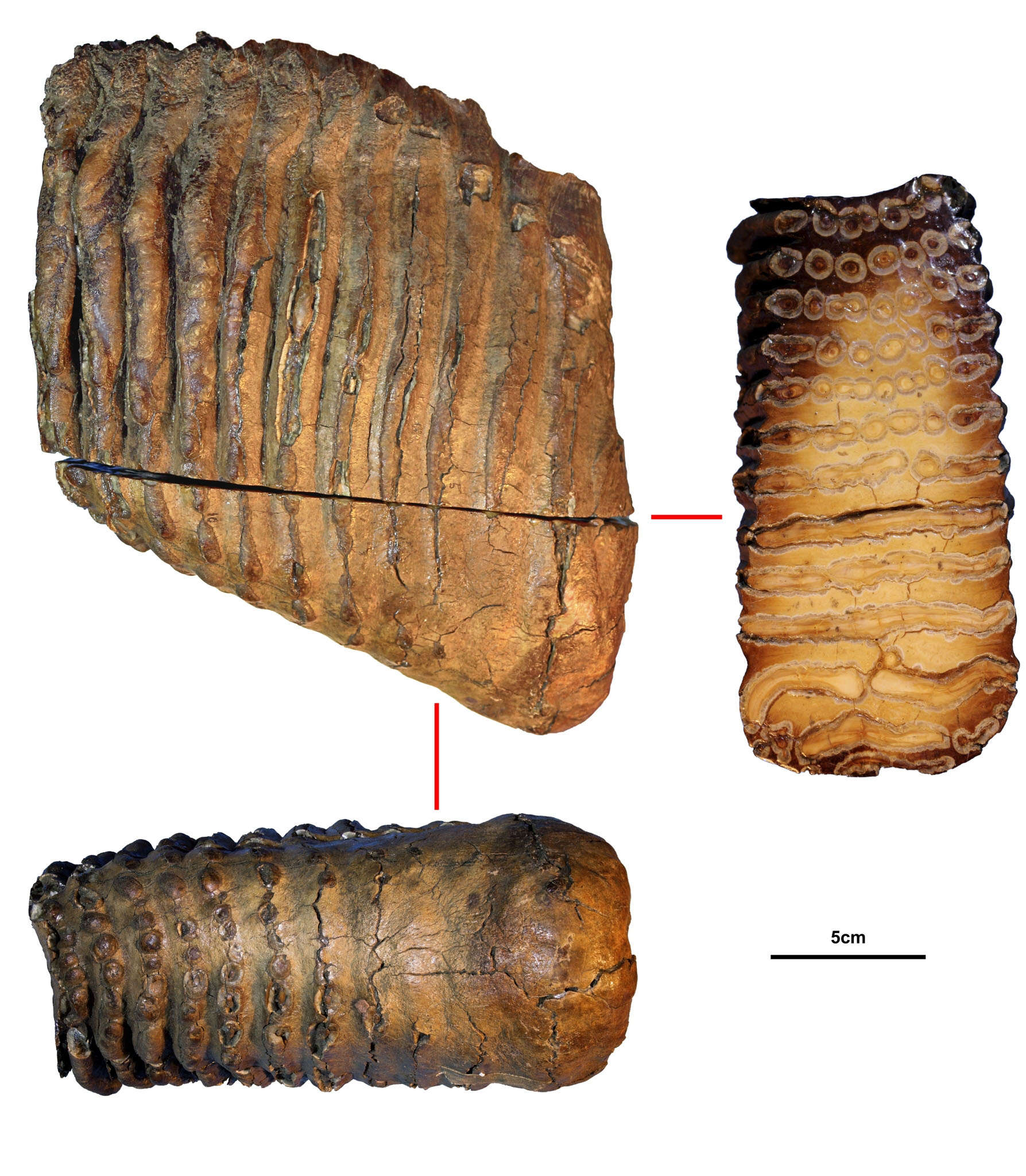

Not only did Dalén and his team manage to sequence million-year-old DNA from the mammoth’s teeth (below), but this made it possible to compare aspects of the mammoth genome going back up to a million years. These genes gave away how mammoths adapted to subfreezing temperatures and evolved everything else it took to survive in a land of eternal winter. They were hairy for a reason. Krestovka mammoths already had thick hair, fat deposits, thermoregulation and tolerance of the extreme cold before woolly mammoths were even a thing. There was also something else about the mammoth genome that surprised Dalén.

“Tracing genetic changes across a speciation event hasn’t been done before for any animal species,” he said. “What it allows us to do is to investigate an age-old question in evolutionary biology, which is whether adaptive evolution (such as genetic change caused by natural selection) happens faster during speciation events as compared to periods between speciation events. It actually occurred at the same pace.”

Now that the mystery mammoth has all but been brought to life again, Dalén and his colleagues want to keep unearthing things about how mammoths spread and evolved, especially how very early European and American mammoths could have been related to the Krestovka mammoth. They are also looking in to doing this for other types of animals that can be traced back to an ancestor around a million years old.

“There are many other mammalian species that trace their origin to the time period around one million years ago,” Dalén said, “and we are now starting a project to also look at their evolution.”