Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Sound the dive alarm! This marine reptile could plunge deep into prehistoric waters

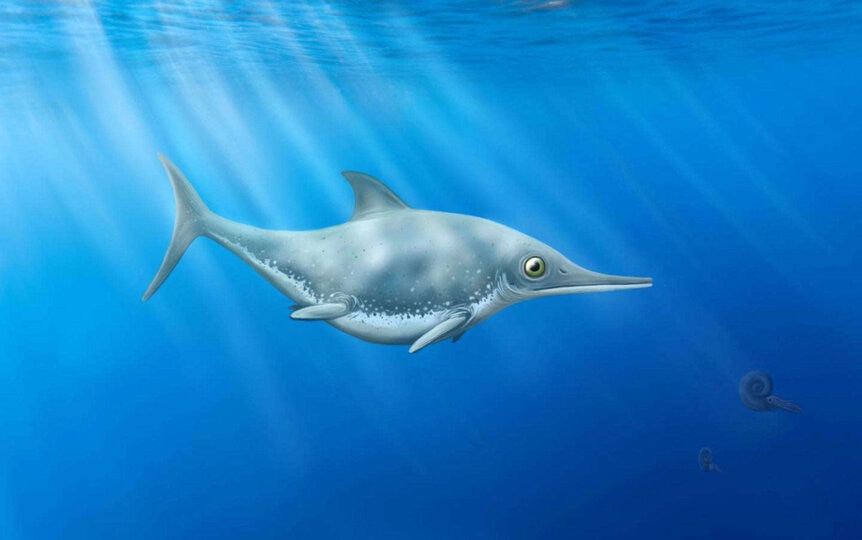

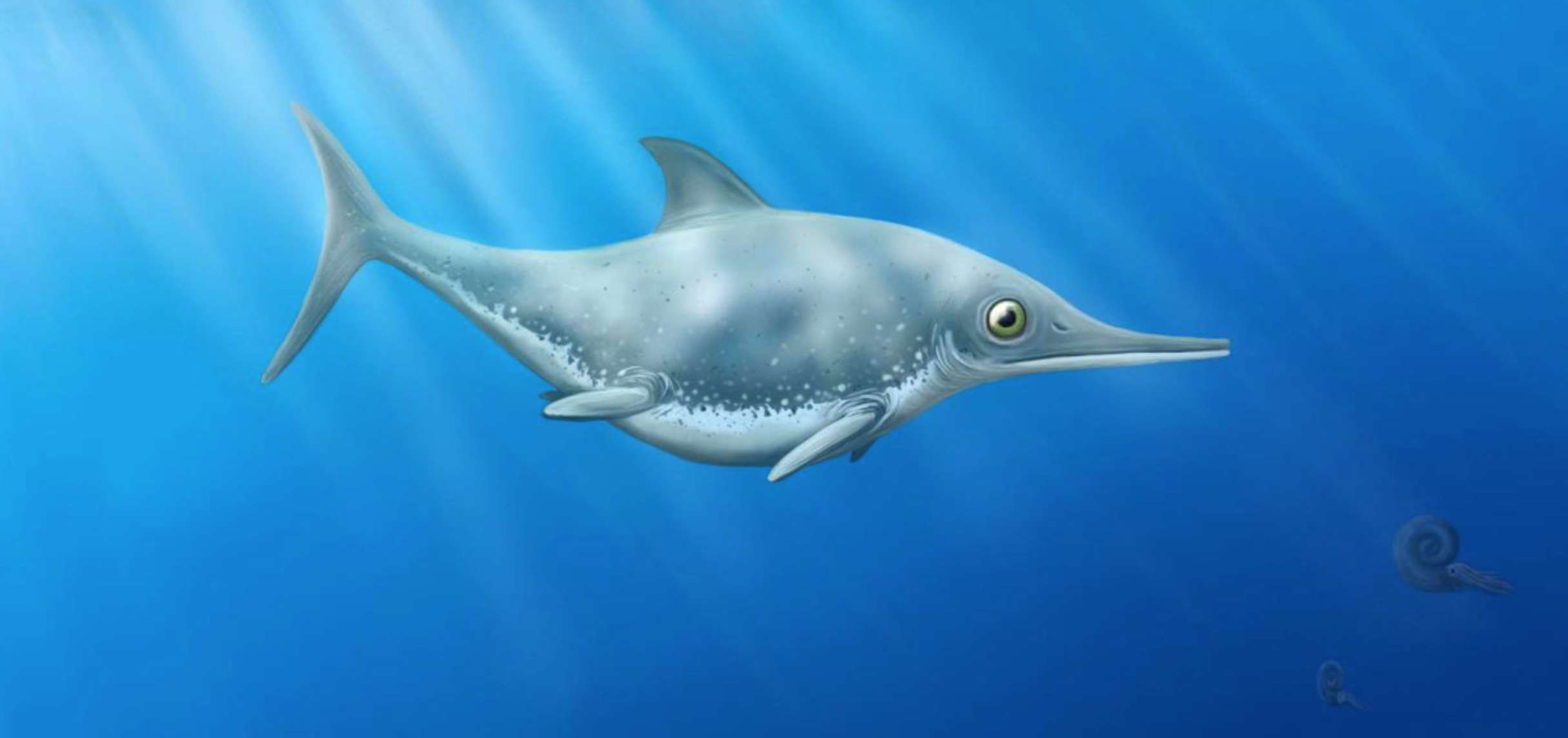

Like some ancient needle-nosed submarine able to make impressive plunges down into prehistoric seas, a new species of 150 million-year-old marine reptile was recently identified after being initially unearthed back in 2009 from a marine deposit off the English Channel coastline near Dorset.

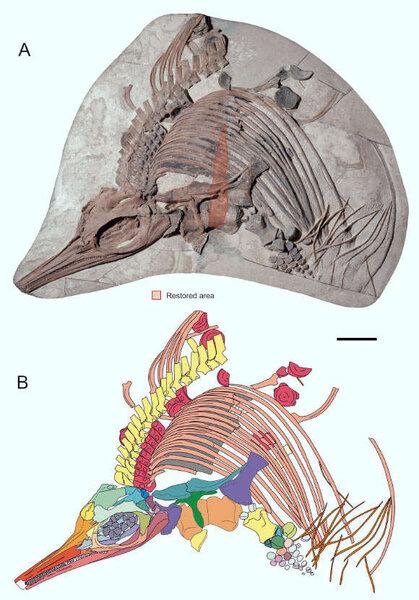

This particular UK specimen is extremely well-preserved and represents a fortuitous find in Late Jurassic ichthyosaurs of all types.

As detailed in a new study recently published in the online journal PLOS ONE, ichthyosaurs are extinct medium to large-sized marine predators that thrived during the Age of Dinosaurs. They first appeared in the Early Triassic roughly 250 million years ago and prowled the primeval oceans until the Late Cretaceous approximately 90 million years ago.

"This ichthyosaur has several differences that makes it unique enough to be its own genus and species," explained paleontologist and co-author Megan L. Jacobs, a Baylor University doctoral candidate in geosciences.

"New Late Jurassic ichthyosaurs in the United Kingdom are extremely rare, as these creatures have been studied for 200 years. We knew it was new almost instantly, but it took about a year to make thorough comparisons with all other Late Jurassic ichthyosaurs to make certain our instincts were correct. It was very exciting to not be able to find a match."

Measuring in at nearly 6 feet long, this was a stout, barrel-like creature whose remains were discovered eleven years ago by fossil collector Dr. Steve Etches at the White Stone Band outcropping in Rope Lake Bay, Dorset after a cliff face disintegrated and exposed the skeleton. It was nicely entombed in a slice of earth that at some point over the eons had been buried 300 feet deep in a section of limestone seafloor.

"Now that the new sea dragon has been officially named, it's time to investigate its biology," said study co-author David Martill, Ph.D., professor of paleontology at the University of Portsmouth in Portsmouth, United Kingdom. "There are a number of things that make this animal special. It's excellent that new species of ichthyosaurs are still being discovered, which shows just how diverse these incredible animals were."

This amazing species' fossil is now part of The Etches Collection Museum of Jurassic Marine Life in Kimmeridge, Dorset and has been officially named Thalassodraco etchesi, meaning "Etches sea dragon."

"This animal was obviously doing something different compared to other ichthyosaurs. One idea is that it could be a deep diving species, like sperm whales," Jacobs noted. "The extremely deep rib cage may have allowed for larger lungs for holding their breath for extended periods, or it may mean that the internal organs weren't crushed under the pressure. It also has incredibly large eyes, which means it could see well in low light. That could mean it was diving deep down, where there was no light, or it may have been nocturnal."

Ichthyosaurs began life as lizard-style animals crawling on terra firma and eventually evolved into the hybrid dolphin/shark-like oceanic menace seen now as fossilized bones.

Their four limbs transformed into wide flippers for efficient paddling. With its much tinier flippers, Thalassodraco etchesi could have navigated by a unique style of swimming that differentiated itself from other mainstream ichthyosaurs and was certainly capable of diving down far into the dark waters of Jurassic oceans.

"All other ichthyosaurs have larger teeth with prominent striated ridges on them, so we knew pretty much straight away this animal was different," Jacobs added. "They still had to breathe air at the surface and didn't have scales. There is hardly anything actually known about the biology of these animals.

"We can only make assumptions from the fossils we have, but there's nothing like it around today. Eventually, to adapt to being fully aquatic, they no longer could go up onto land to lay eggs, so they evolved into bearing live young, tail first. There have been skeletons found with babies within the mother and also ones that were actually being born."

Jacobs further explained that this remarkable new specimen of ichthyosaur probably perished from natural causes or was potentially killed by larger, hungrier predators before it fell to the bottom of the sea.

"The seafloor at the time would have been incredibly soft, even soupy, which allowed it to nose-dive into the mud and be half buried," she said. "The back end didn't sink into the mud, so it was left exposed to decay and scavengers, which came along and ate the tail end. Being encased in that limestone layer allowed for exceptional preservation, including some preserved internal organs and ossified ligaments of the vertebral column."