Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Our galaxy is blowing *enormous* hot bubbles into space and no one knows why

There are two enormous bubbles of extremely hot gas expanding from the core of the Milky Way has into near-galactic space, centered right on the supermassive black hole in our galaxy's heart. The thing is, no one knows if the black hole is their power source, or if it's something else. But new observations give more detail on the structure of these bubbles, and may help astronomers tease out what's going on.

The gas bubbles were first seen because they're emitting super-high-energy gamma rays, the highest energy form of light. They were mapped by NASA's Fermi observatory, and got the nickname Fermi Bubbles. These features are enormous, tens of thousands of light years in size, and so big they stretch across two-thirds of the sky as seen from Earth.

That's incredible. We're 26,000 light years from the galaxy's center, but these structures are so huge they cover a significant fraction of our sky. However, they emit no visible light we know of, so we can't see them by eye.

They appear to be bubbles, thin-walled structures filled with hot gas. However, hot gas on its own can't make gamma rays. Most likely there are powerful shock waves as the gas plows into the thin material floating around just outside our galaxy, as well as strong magnetic fields locked in with the gas; together these can accelerate subatomic particles to incredibly high energies, making them capable of making the gamma rays Fermi saw.

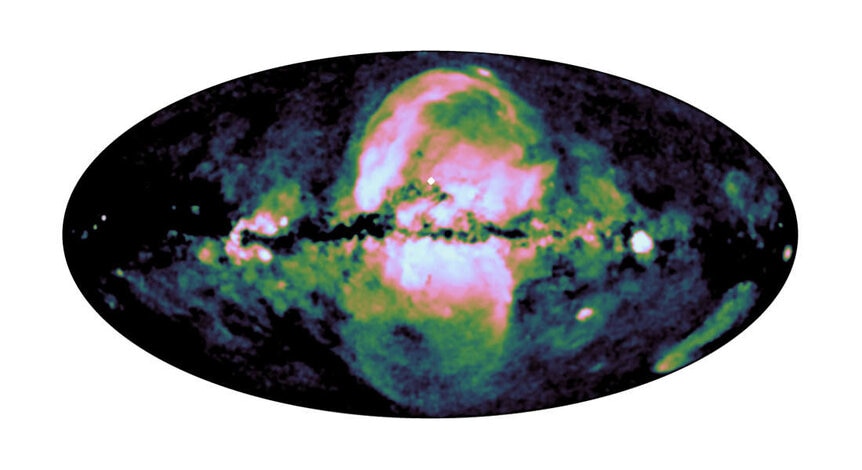

These bubbles have been seen in radio waves as well, likely also caused by magnetic fields. And now new observations show they're filled with X-ray emitting gas, too. And they're even bigger.

These observations were made by eROSITA, the extended ROentgen Survey with an Imaging Telescope Array, a German/Russian space-based observatory that can detect X-rays. It's a survey instrument, meaning it looks at large swaths of sky to see what's happening on large scales.

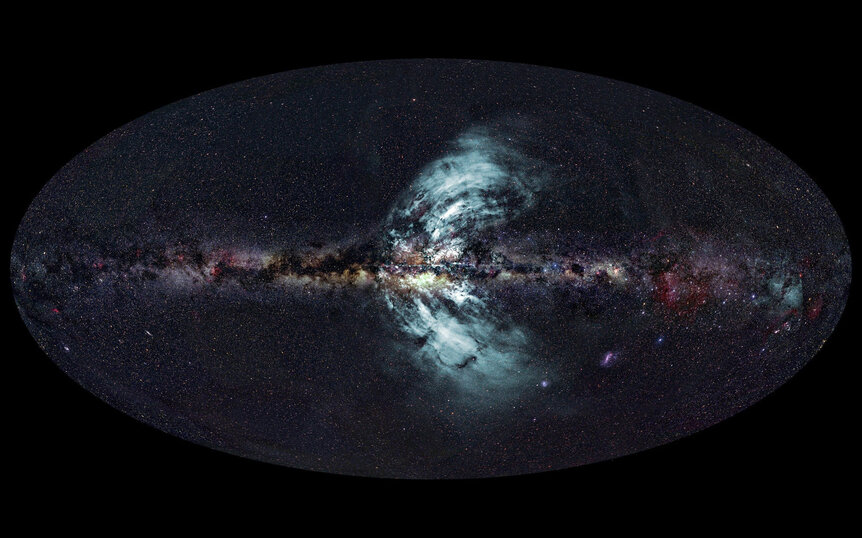

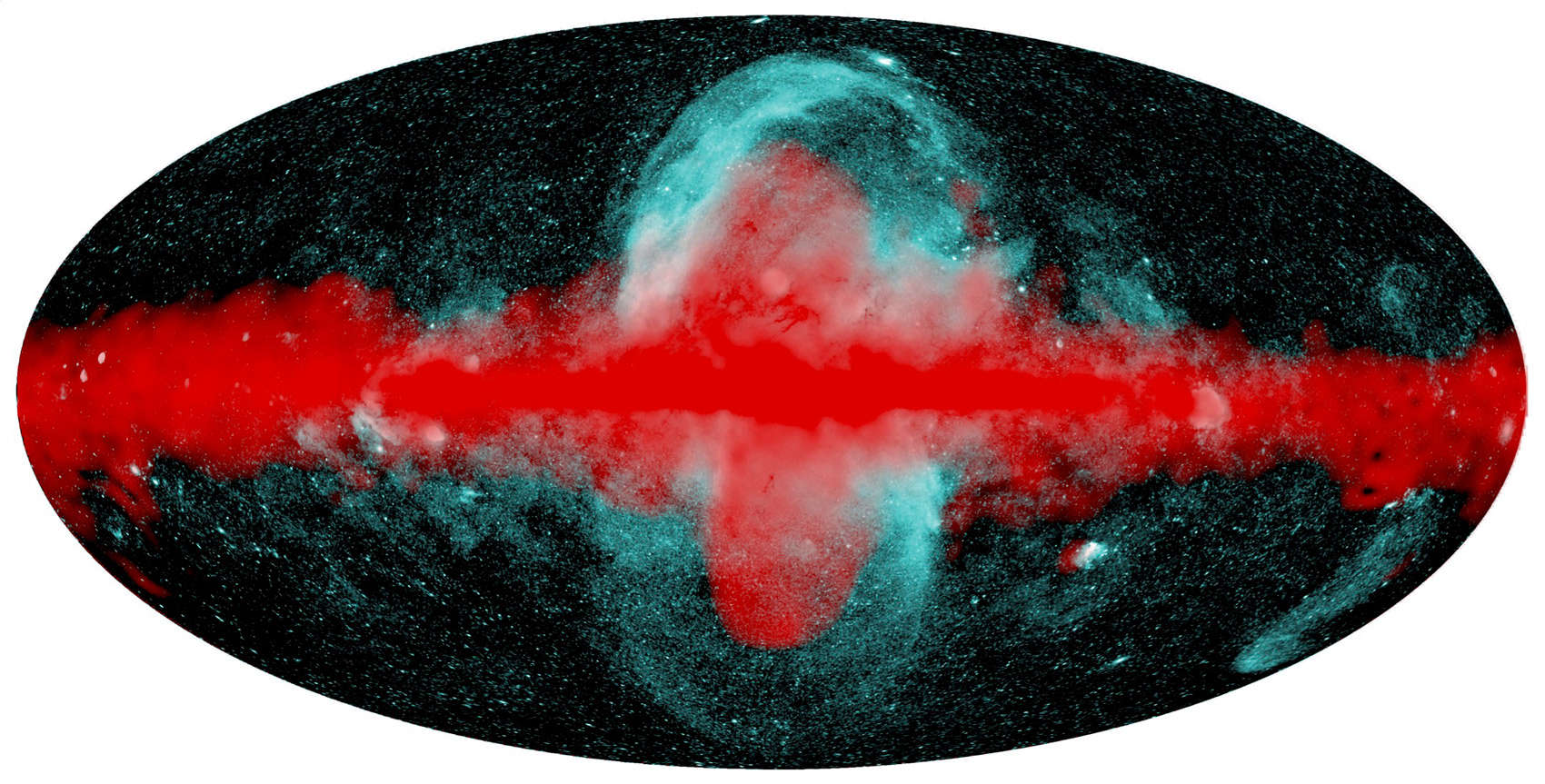

Looking at medium-energy X-rays over the entire sky, what it saw was this:

We are inside the plane of the flat disk of the Milky Way which is loaded with thick dust, so we see that in silhouette across the center. You can see the huge lobes emitting X-rays expanding away from the galactic center in the top and bottom of the image, and they look an awful lot like the Fermi bubbles. But, amazingly, at 55,000 light years long they're even bigger.

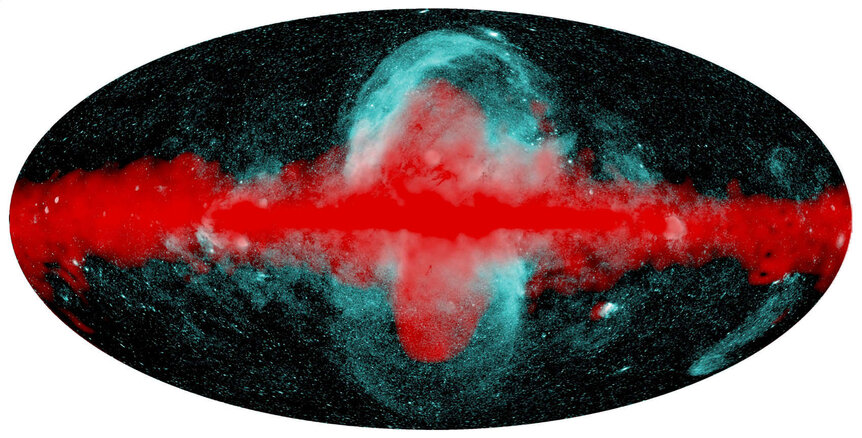

Here is the eROSITA (in teal) and Fermi (red) bubbles superposed together to show you the scale:

The bubbles seen by eROSITA look more like shells to me as opposed to being filled with gas. Something filled with gas looks more solid, filled-in, whereas something that's thin-shelled looks like a soap bubble or a ring in space. We see that a lot when stars die to form planetary nebulae.

It makes me wonder if the eROSITA structures are an expanding front of gas plowing into material outside the galaxy and piling it up like a snow plow, whereas the Fermi bubbles are from expanding gas behind that front and filling in the cavities left behind by them. Hmmm.

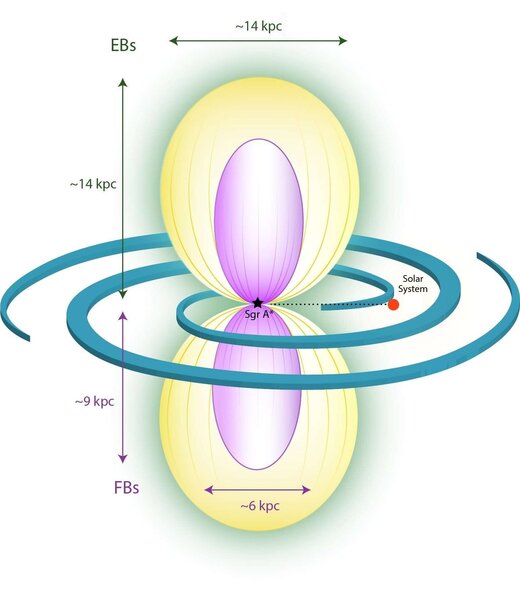

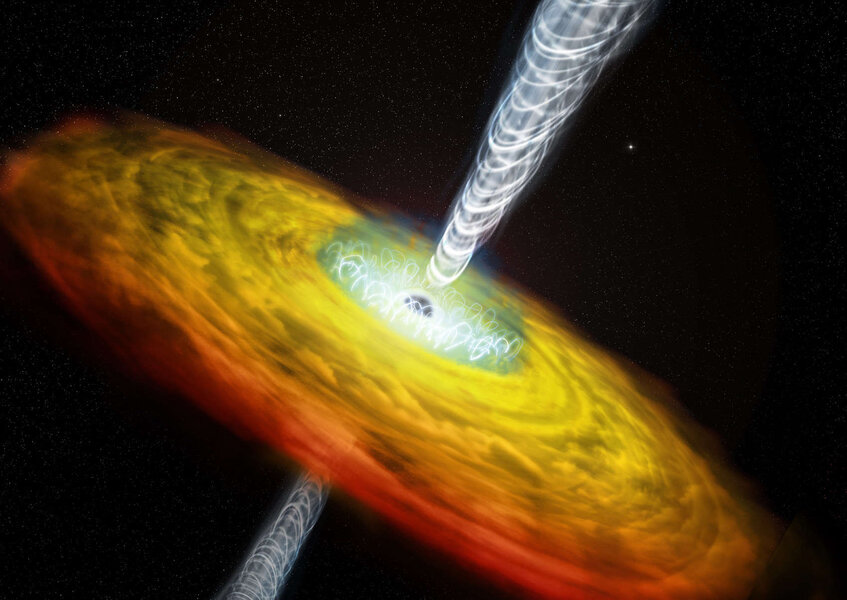

To give you a better picture, here's a schematic of what's going on:

The purple shows the gamma-ray Fermi bubbles, and the yellow is what's seen by eROSITA in X-rays. The blue spirals represent the Milky Way's spiral arms, with the Sun's location noted. Astronomers use parsecs for distance quite a bit, and a kpc is 1,000 parsecs. That's equal to 3,260 light years, and the galactic disk is about 120,000 light years across.

So yeah, these structures are flipping enormous. The energy it takes to blast gas out of the galaxy at scales like this is mind-crushing. In just X-rays it's equivalent to 100,000 supernovae. It looks like whatever did this happened about 20 million years ago.

So what did happen? Did 100,000 massive stars all explode?

Well, maybe. Yes, seriously, that could be what happened. There have been bursts of star formation in our galaxy, and there is some evidence that the Fermi bubbles were blown out by something like that. A huge burst of star formation creates lots of massive stars that can explode, and some observations point toward that being the cause.

On the other hand, sitting right in the center of the galaxy is a whopping big black hole, called Sgr A* (literally "Sagittarius A-star"). Gas falling into the black hole forms into a huge disk that gas incredibly hot, and as it spirals around its magnetic field gets wrapped up with it, shaped into two enormous cone-shaped vortices that can blast matter out of the galaxy at tremendous speed.

Right now our supermassive black hole is quiescent, but millions of years ago, who knows? Perhaps a huge cloud of gas and dust fell into it, and caused an epic eruption that formed the eROSITA and Fermi bubbles. The blast of energy involved would have outshone all the stars in the galaxy combined, and for a short period the Milky Way would've been a quasar.

One small problem with all this is the timing. The eROSITA data suggest it happened 20 million years ago, but other observations show maybe it was only 3 million years ago. Those are not necessarily incompatible; it can be hard to get the ages of events like this. There are large uncertainties, with a whole pile of things that can throw the estimates off.

But this is all good! These ridiculously gigantic features are still quite mysterious, and difficult to observe because of their huge size. It takes all-sky surveys to see them at all, let alone get an idea of their detailed structure. We've seen them in gamma rays and radio waves, and now X-rays. The more ways we see them the better we'll understand them... and whatever colossal event it was in the center of the galaxy that created them.