Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Quarter-million-light-year long threads in an active galaxy have astronomers… engaged

In the premier episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, "Encounter at Farpoint", the Enterprise has to solve a mystery at a distant planet — which turns out to be (spoilers!) that the inhabitants of the planet have been holding a huge space-faring jellyfish-like creature captive. At the end of the episode, after Picard and crew save it, the creature flies up into space, meeting its mate in orbit, and they entwine long tentacles as they (presumably joyfully) reunite.

This episode premiered in 1987. Why bring it up now?

Because maybe Captain Picard should've checked the historical records. If he had found old 21st century observations of the galaxy ESO 137-006, the mystery would've been solved a lot faster. But then, a different mystery would've taken its place.

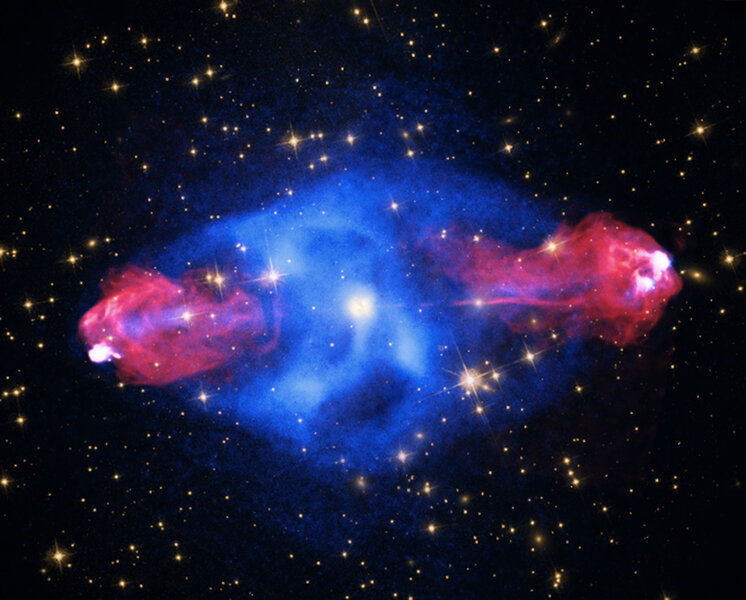

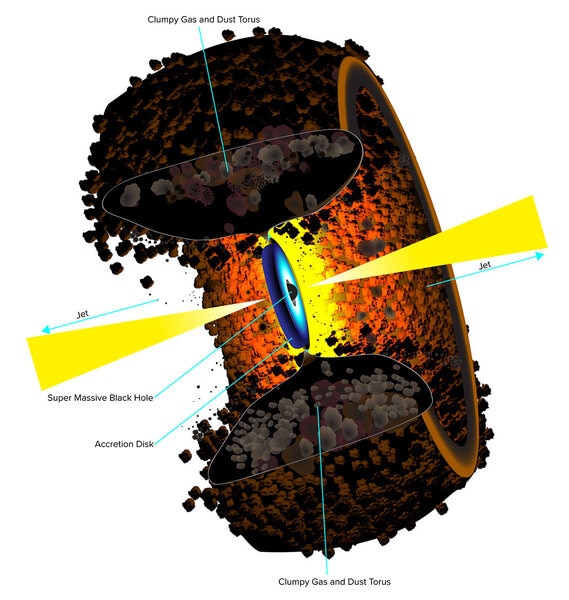

ESO 137-006 is what we call an active galaxy. It has a supermassive black hole in its core, one that has a huge swirling disk of matter orbiting it, well outside the event horizon (the Point of No Return). This accretion disk is incredibly hot due to friction, and glows so brightly it outshines the entire rest of the galaxy!

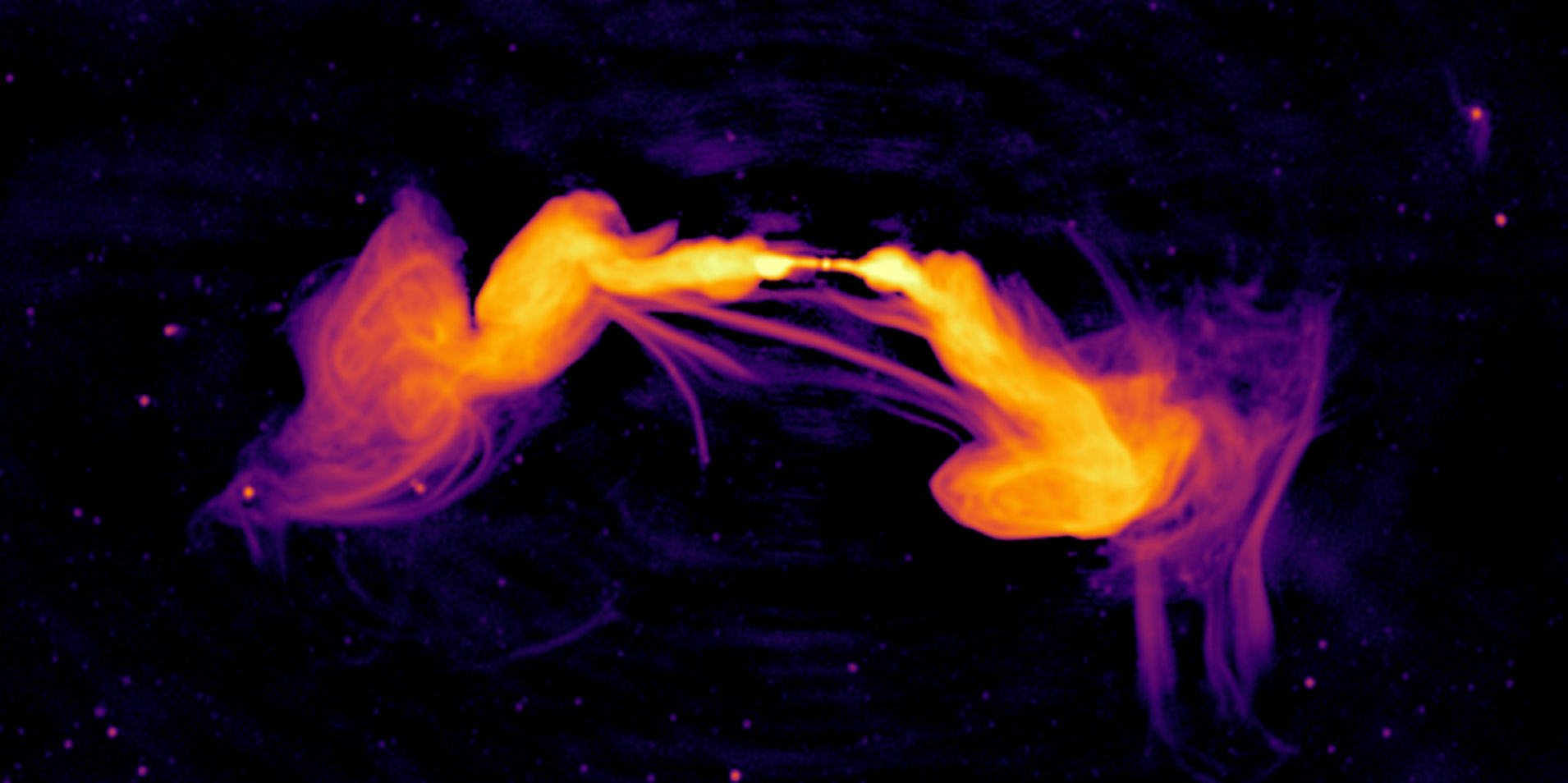

But that's not all it does. For reasons not entirely understood, twin beams of matter are shooting away up and down from the disk, focused by the intense magnetic fields of the disk (or possibly by the black hole itself). Astronomers call these jets, and everything about them is terrifying. For one thing, the material in them is fiercely accelerated up to very nearly the speed of light! For another, these jets are so powerful that they blast right up and out of the galaxy, extending for well over a million light years end-to-end, a dozen times larger than the galaxy itself!

Holy wow.

ESO 137-006 is part of a large cluster of galaxies called the Norma Cluster, a little over 200 million light years away. Clusters like that have a lot of gas in between the galaxies, and ESO-137-006 is falling through that gas toward the center of the cluster. That has two effects. For one, the jets have to ram their way through that gas. This slows them down, and at the ends they puff up into huge lobes of material, similar to mushroom clouds in big explosions or cumulonimbus thunderstorm clouds. Also, as the galaxy moves through the cluster that gas acts like wind, blowing the jets back, bending them. The result looks like a Q-tip that got stepped on.

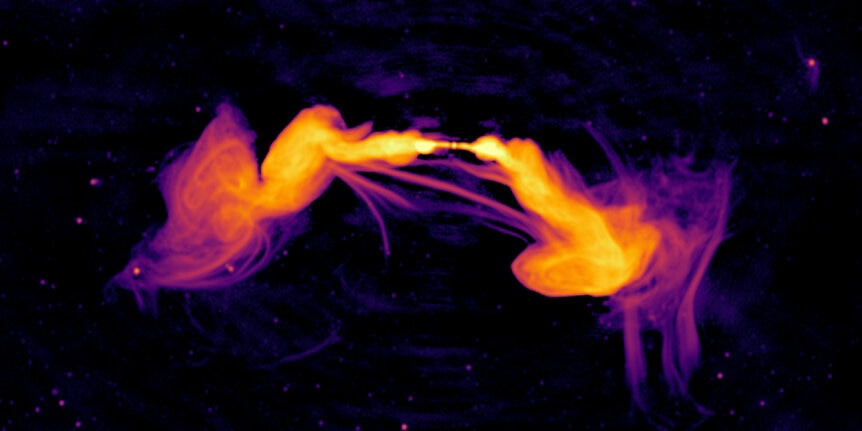

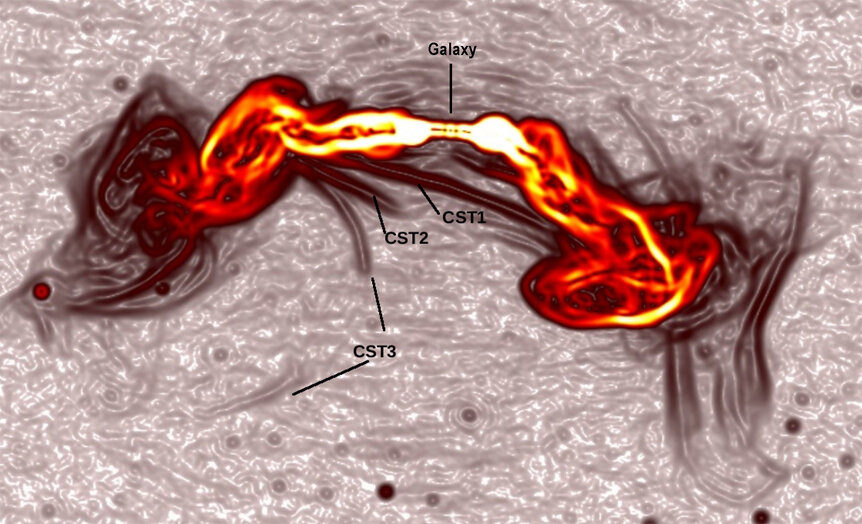

ESO 137-007 has been observed many times, but the best view is with radio telescopes, since the jets and lobes glow brightly in radio waves. They've been mapped pretty well… but then MeerKAT came on the scene. This is a very sensitive radio telescope array that has phenomenal resolution, the ability to see very fine details. It was used to seek out ESO 137-006, and what it saw was, well, a very strange, new thing: Incredibly long threads that seem to connect the two lobes, even over hundreds of thousand of light years!

What. The. WHAT.

As best the astronomers who made the observations can tell, these are some sort of magnetic effect, maybe the magnetic field of the jets interacting with the field embedded in the cluster gas, dragging electrons along with them. The electrons spiral around the field lines, emitting radio waves in a process called synchrotron radiation. They call these structures collimated synchrotron threads, or CSTs.

But here's the fun part: They really have no idea what's causing them. It's certainly magnetic in nature, and certainly synchrotron emission; the observations clinch that. But how are they formed? Why are they so long? Why are they so narrow? One of them (CST1) is a quarter of a million light years long, twice the length of the Milky Way's disk alone, yet only a few thousand light years in width. These things are really narrow! It appears to connect the two lobes, but that could just be a projection effect.

Another one (CST3) appears to come from the base of one of the jets, then curves back on itself to connect back into the very far tip of the lobe itself. They have no idea why. Another one (CST2) starts straight and then just kinda fades after 80,000 light years. It might connect to the other lobe, but it's hard to say.

Another fun bit: This is the highest resolution and deepest radio image of a double-lobed active galaxy ever taken, and in it these things suddenly appear. That asks an obvious question: How common are these threads? Are they in every galaxy like this, but too faint to see? Or are they somehow specific to ESO 137-006 for some reason, maybe because it happens to be falling through a lot of very hot gas in the cluster?

Yeah, good questions. I bet the answers are good too. It's just that we don't know what they are*.

I wish I could give you an explanation, but I don't have the Enterprise or Data or Q to help out here. In this case, we're on our own. But that's OK! Despite Q's constant negging, we're a clever species, inquisitive and stubborn. Presented with something like this we'll observe more galaxies, build more telescopes, use existing telescopes in different ways, and we'll figure this out. It's what we do.

We don't know what these structures are… yet. And that's the most hopeful word in science. It means we're still boldly going.