Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Could we live on Kepler-22b, like Raised by Wolves' human colonists?

Raised by Wolves is a fine show, its got an interesting if not wholly unique setup, it’s visually arresting, and a directing stint by Ridley Scott is nothing to scoff at. Still, it’s curious the writers set the show on Kepler-22b, an actual planet which made some headlines in 2011 for being the first confirmed Earth-like exoplanet to be discovered inside its parent star’s habitable zone.

There’s nothing about the show, at least so far, which necessitates it being set in a real place, and doing so invites comparison between what’s presented on screen and what we know about the actual locale.

To date, we know precious little about Kepler-22b, but what we do know stands in stark contrast to the world colonized by the characters of Raised by Wolves. There’s little evidence that the actual Kepler-22b resembles the world we see on screen in any way whatsoever. These worlds, the fictional and the real, seemingly share a name and nothing else.

The answer to why the creators chose to set the world there, when any number of other worlds, real or imagined, might have better fit their vision, is one we can’t answer within the scope of this article. So we’ll set our sights on another query: what might it actually be like to live on Kepler-22b?

KEPLER SPACE TELESCOPE

The search for worlds outside our solar system has been ongoing for centuries, but has really only taken shape in the last few decades. The first confirmed detection of an extra-solar world was confirmed only in the 1990s.

Since that time, more than 4,000 exoplanets have been discovered, most of them by the Kepler Space Telescope, between 2009 and 2018.

Kepler used the transit method to detect extra-solar planets. Pointing itself at specific regions of the sky, Kepler would measure the apparent brightness of stars, looking for intermittent dips in the amount of light making its way to the aperture. A decrease in the apparent light suggested the transit of an object. But that wasn’t enough to confirm the existence of a planet. Any number of phenomena can cause a temporary reduction in the brightness of a star. That’s why Kepler required at least three dimming events at repeated intervals in order to confirm the existence of a planet.

Kepler was designed in such a way that it was able to continuously view an entire region of space, not just one specific star. This was important because transit events can be brief, and breaking contact might mean missing them.

The sheer number of worlds that Kepler discovered is a testament to how well the mission was designed and carried out. The overall mission lasted nine years before the telescope’s control system was depleted and it was retired, more than five years longer than its planned mission duration. It uncovered so many planets that nearly all of them are unknown to the general public.

Kepler-22b is the exception because it was the first. The first Earth-like world in a habitable zone. The first confirmed world outside our solar system which offered the possibility of another place that we might live, if only we could get there.

KEPLER-22b

Popular headlines at the time of Kepler-22b’s discovery positioned it as though it were another Earth circling a distant star. That’s true only in the barest terms, when compared against the variety of worlds which exist in the galaxy.

In truth, despite its many similarities, Kepler would still look entirely alien to us if we had the chance to visit.

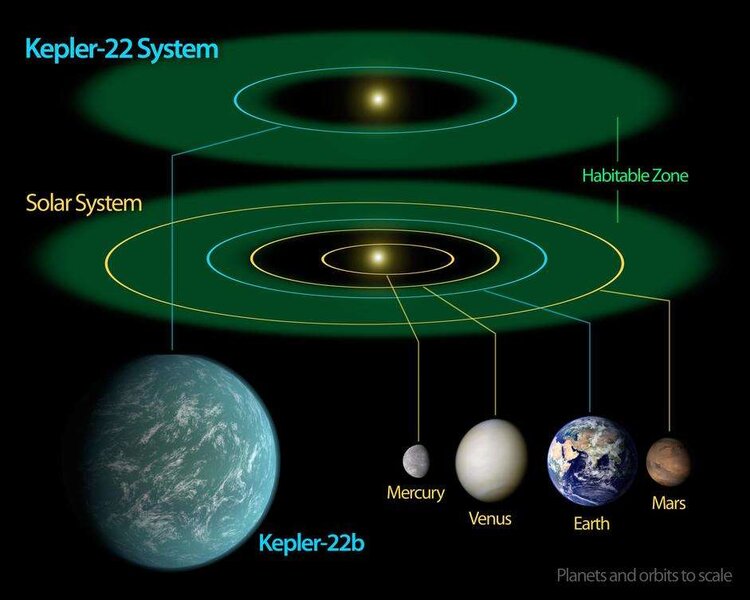

It orbits a star pretty similar to our own. It’s a yellow dwarf, but a little smaller, a little older, and a little fainter than Sol. Its size and brightness means it doesn’t put out as much heat as we’re accustomed to. Luckily, Kepler-22b orbits a little closer to its parent star than Earth does to its, which more or less evens things out.

Distance from a star isn’t the only contributing factor when it comes to whether or not a world is habitable, though. It’s important to know what sort of atmosphere a planet has, as that has as much, if not more impact on the average temperature.

For evidence of this, we need look no further than our own planetary neighbors. If distance to the Sun were the only consideration, we’d expect Mercury to be the warmest planet, but that isn’t so.

Despite being considerably further from the Sun, your average day on Venus is warmer than even the hottest locales on Mercury, and that’s owed entirely to its oppressive atmosphere.

Kepler was not equipped to identify atmospheric makeup so we’re relying on speculation and best guesses, but the belief is that Kepler has the climate of a nice comfortable spring, somewhere around 72 degrees Fahrenheit (22 C).

It’s also worth noting, some models imagine Kepler rotating on its side, with each pole facing the sun for half of its 290 day orbital period, which might further contribute to a mild climate as stellar engery equalizes over time. While this sort of tilt isn't unheard of, our own Neptune spins in this way, there's no confirmed evidence as to 22b's tilt, one way or the other (so to speak).

If we assume the atmosphere is similar to Earth, we’re dealing with a planet with breathable air and light jacket weather. Sounds idyllic. In fact, it sounds a lot better than the world presented to us in Raised by Wolves. At least until we consider the rest of the planet’s properties.

SIZE AND STRUCTURE

Kepler-22b has been described as Earth-like in size, which is true to a point. In actuality, it’s 2.4 times the diameter of Earth, which doesn’t sound so bad until you remember those volume calculations you learned in grade school.

Remember, 2.4 times the diameter does not equate to 2.4 times the mass. Here, again, we run up against the unknown. Without knowing the planet’s composition, we can’t calculate its mass. It's possible Kepler-22b is mostly gaseous, in which case it might not be all that massive, but also may not be a very fun place to live. It’s possible it’s comprised very similarly to Earth, mostly made of rock, iron, ice, and water. In which case its mass would be something like 10 - 15 times that of Earth.

Again, we can’t know all of the variables at play on the planet’s surface (here’s a fun thought experiment which illustrates some of the possibilities), but it’s likely even in an ideal scenario, that the gravitational forces apparent on the surface are more than double what we’d experience on Earth. It isn’t necessarily a show stopper, but imagine walking around all the time while carrying yourself on your back.

The sheer force of everyday gravity would make living and moving on Kepler a chore. The good news is, such high gravity would likely mean those giant lizards from the show wouldn’t or couldn’t exist there, at least atop a planet with a rocky surface. Gravity here on Earth creates a sort of upper limit to the size of animals before the weight of their own bodies pulls them down. Higher gravity typically means smaller animals. This is true even at the cellular level.

It’s the reason that the largest animals which have ever existed on Earth live in the water, where the pull of gravity is minimized. Which brings us to the final point about Kepler-22b.

It’s likely the planet is covered in a global ocean. In an interview, one Kepler scientist suggested Kepler-22b might be more like Neptune than Earth, with a rocky core and a large planet-spanning ocean. Good news for the giant lizards, not so much for any human colonists hoping to set up a new home there.

Future exoplanet missions may uncover more details about this intriguing distant world, but what we know (or suspect) so far paints an entirely different picture than the one which has been presented on screen.

Still, even if future knowledge eliminates Kepler-22b from the pool of habitable planets, the science of exoplanet research is making one thing abundantly clear. The galaxy, and the universe, is absolutely littered with worlds, many of them probably capable of sustaining life of a kind. The future of space exploration is bright and alluring, let’s just hope that future exploration is fueled by a hunger for knowledge, and not a flight from danger, or from ourselves.