Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

LucasArts was the pinnacle of early '90s computer games, fight me on it

When waxing nostalgic about retro gaming, I tend to think of one particular kind of experience. I missed out on the Atari age, and though I did have an original Nintendo Entertainment System, I was fairly hopeless with almost every title it had to offer. The heyday of retro gaming, for me at least, came via computer. I don't imagine myself mashing buttons when I think of the past and gaze at clouds — I'm more likely to fondly recall pointing and clicking.

The early part of the 1990s was an especially grand period in the age of "point and click" adventure games for the computer, with the movements of a mouse generally overtaking a text-based interface. Sierra On-Line was a giant during this time, and it was famous for such series as King's Quest, Space Quest, Police Quest, and Leisure Suit Larry. The earlier games in all of these series had you typing commands at the bottom of the screen, and these commands were almost always misconstrued. Typing curses didn't get you anywhere — believe me, I tried.

Sierra eventually transitioned to a smoother point and click system, taking a cue from the other giant of the time: LucasArts, once branded as Lucasfilm Games.

The company itself was founded well before the '90s, and the man behind it, you may have guessed by the name of the company, was Star Wars creator George Lucas. Looking to expand into possible global domination in 1979, Lucas created the Lucasfilm Computer Division. It included one branch for developing computer games and another branch for developing graphics. The graphics division, it should be noted, spun off in 1982 and eventually became a little company that you may have heard of called Pixar.

The gaming branch reorganized into the Lucasfilm Games Group, and oddly enough it didn't have the rights to make Star Wars games at first. Those rights were owned by Atari, and this is why the group had to go about creating its own titles, which had nothing to do with the Star Wars story.

After a few games were developed in tandem with other companies, the group's first big moment came with Maniac Mansion in 1987.

The game had an original (and rather nutty) story, and it went along with the group's charter, which was to "make experimental, innovative, and technologically advanced video games," according to Rob Smith's 2008 book, Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts. What made it so advanced was the engine that drove the game, which was called SCUMM. The name stood for "Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion."

For all intents and purposes, SCUMM is what made fetch happen. Players could use the mouse to move their character around the screen and interact with the surroundings by clicking on a series of verbs listed below. For instance, an object in a room, when combined with a verb, would allow the character to "read book," and so forth. It may sound dumb, but it was, and still is, AWESOME. This engine, developed by Ron Gilbert, drove the company that would eventually rebrand itself into Lucasfilm Games before arriving at its final iteration, LucasArts.

LucasArts may not have had the rights to Star Wars, but Indiana Jones was another matter. In 1989, it found huge success with a SCUMM-driven game adaptation of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Incidentally, this was the first point and click adventure game I ever played, and it only fueled my love of the third Indy film... a love that only grows stronger every year.

Players were given an "IQ" rating, which stood for "Indy Quotient." Doing things like Indy would do them either raised or lowered the rating. The game also came with a hard copy of a fully written "grail diary," which proved vital to solving some of the game's puzzles. I still have mine — even without the game itself, it's a fun read.

After Indy whipped his way to glory, the company came along with the surreal fantasy Loom in 1990, but the real crown prince of Lucasfilm Games came after that.

The Secret of Monkey Island (and the series that it spawned) may be its most popular and nostalgic romp. It's a spin on the pirate genre, and you play as Guybrush Threewood, a young man who yearns to be a pirate. The game was (and still is) beloved for its humor, breaking the fourth wall every other second and often acknowledging that it was a game. Previous LFG titles had done this to an extent, but Monkey Island truly went all the way.

The sequel, Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge followed very soon after in 1991, and then Indy crashed the party once again in 1992 with Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. Indy wasn't roughly bound by the story of a film anymore — Fate of Atlantis told a completely original Indy tale, featured a new artifact (pretty much Atlantis itself, naturally), and introduced some new characters and villains to Indy's lore. The player was also given the option of taking different paths through the story depending on their playing style. My style was losing, so I lost pretty often. Indy died a lot when I played these games. No time for love!

The company's winning streak continued with Day of the Tentacle in 1993 (a sequel to Maniac Mansion), and the biker adventure Full Throttle in 1995. Steven Spielberg got in on some of the fun, helping to develop The Dig, which eventually also came out in 1995 after many years of development. The project began as a movie but was deemed to be too expensive, so this tale of astronauts trapped on an alien world became a game... with a little added help from Industrial Light & Magic.

It should be noted that aside from the classic point and click games, LucasArts made some interesting flight simulators.

It eventually gained the rights to Star Wars back, and while the galaxy far, far away never got the SCUMM treatment, it did get some flight sims with the popular X-Wing series. A more arcade-like experience came with Star Wars: Rebel Assault in 1993, and its sequel, Rebel Assault: The Hidden Empire in 1995. The latter game is notable because of story sequences displayed in full video, which featured actors using actual props and costumes from the Star Wars movies — this game marked the first time that these legacy items (original Stormtrooper armor, for instance) were used for filming since Star Wars: Return of the Jedi.

With all of this pointing, clicking, and flight simulating going on, why did things change? What happened, exactly? The seeds of point and click's death had already been sewn, it turned out. The question of "what happened" can really be answered with one word: Doom.

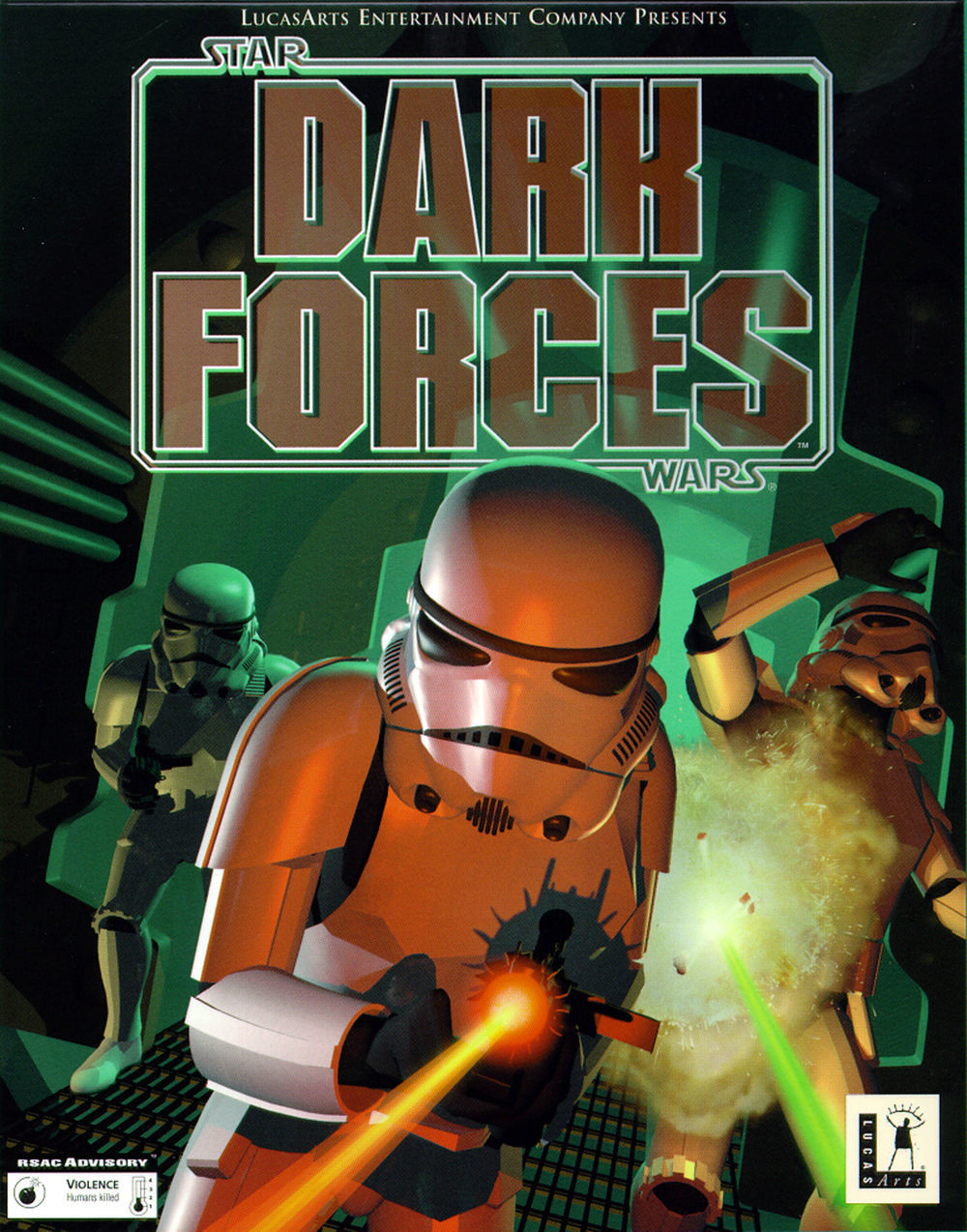

This famous game from id Software in 1993 ended up being a phantom turning point. It generally began the craze of the first person shooter, something that is still alive and well today. LucasArts tried to keep up with the trend once it was clear it wasn't going away, with Star Wars: Dark Forces being a decent example of their efforts. Still, SCUMM stopped being used in 1998.

Another thing that changed the game (sorry) was Super Mario 64 in 1996, a console game that made players want everything in 3D. LucasArts had a bit of success here, but after a few misfires, the company that once couldn't touch Star Wars had a roster that was nothing but Star Wars. Gamers did get the iconic Knights of the Old Republic, but classics like Monkey Island, while getting updated with better graphics and sound every now and then, were not getting new entries. Pointing and clicking became the sole province of executives giving boardroom presentations.

LucasArts kept on flying despite the changes, though it often worked in tandem with other developers. They eventually did partner with a fledgling Telltale Games on a Monkey Island-based game in 2009, called Tales of Monkey Island. Since then, Telltale itself began to shut down late last year. The utter death of LucasArts came earlier at the hands of the Mouse House.

Disney's acquisition of Lucasfilm in 2012 took all pending projects off the board (including the notorious Star Wars: 1313 game), and on April 3, 2013, the mouse-eared Lucasfilm announced that LucasArts (as people knew it) wasn't really gonna be a thing anymore, though it used more business-like language when making the announcement than I just did, of course.

Very soon after, Star Wars games wound up in the hands of EA, and it started things off with a microtransactional bang by reviving Star Wars: Battlefront, one of LucasArts' more successful FPS games. Fans have been... less than thrilled with EA's treatment of the property. Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order (developed by Respawn and due to be published by EA in November 2019) looks very promising, though. Lucasfilm Games (not the rebranded LucasArts) has also begun something of a mysterious rebirth.

As good as the new Fallen Order game might be, and as sharp as the graphics might look, a part of me will no doubt still wish for the old days that gave us some of the most beautiful pixel art your screens will ever see. I'll miss clicking on random things until I finally figure out what I'm supposed to be doing. Instead, I'll probably just be mashing those buttons. Such is the way of things. The way of the Force.

The legacy still lives on. The old games continue to get revived on platforms such as Steam, and an entirely new generation of game-makers, born and raised on the point and click glory of Lucasfilm Games, has given new life to the form. These independent companies may not use SCUMM (or Indiana Jones) to tell their stories, but they do what the Lucasfilm Games Group set out to do in the very beginning. They make experimental and innovative games, and the artists are often "technologically advanced" enough to be able to create them using an army of one, backed by a single computer.

As a pixel-drawn Indiana Jones once said, "I'm selling fine leather jackets like the one I'm wearing." If you ever played the game, you might find that funny.