Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Sailing the lakes of Titan? Prepare for rough seas.

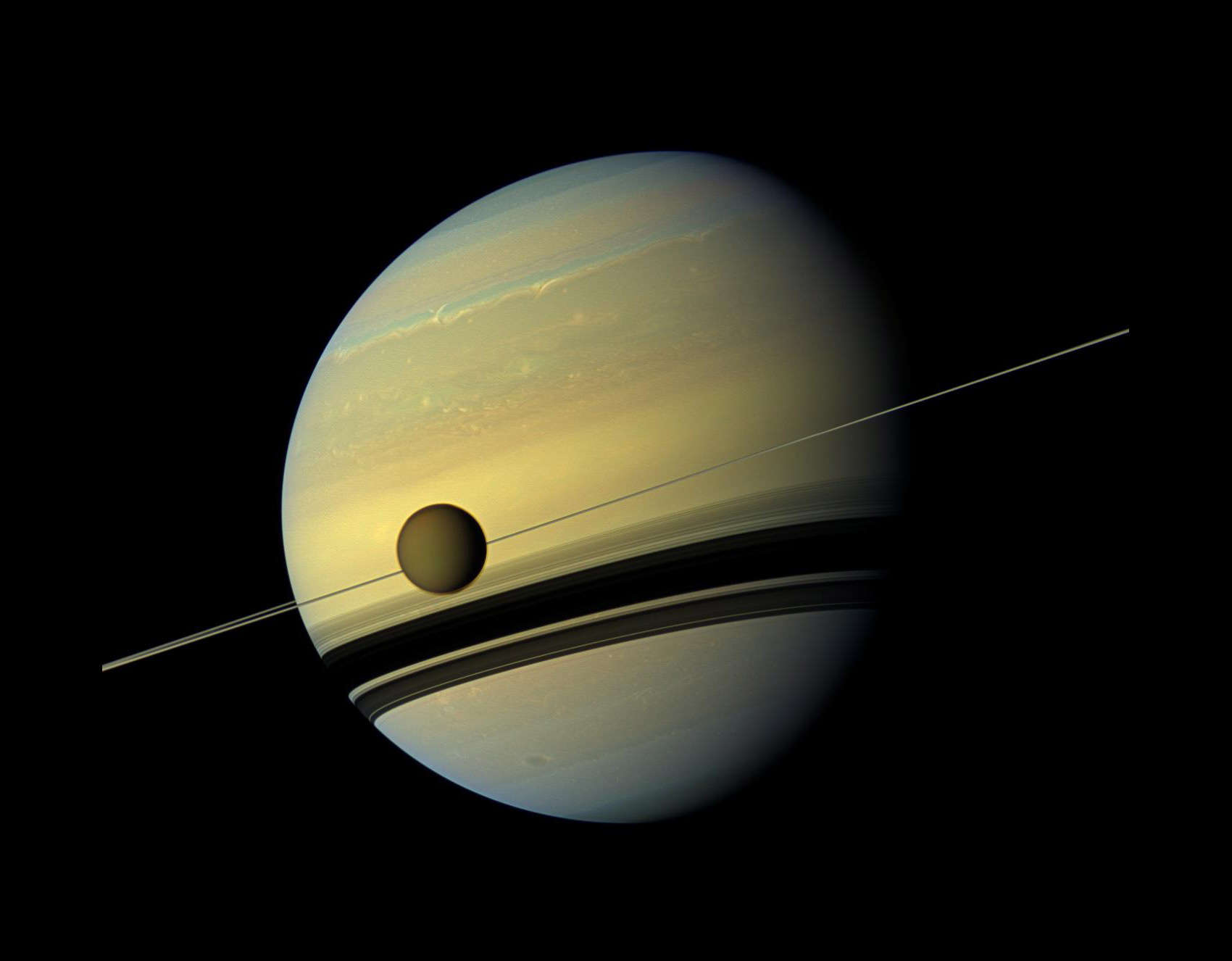

Titan is the largest moon of the planet Saturn, and the second largest moon in the solar system. It's bigger than Mercury! Given that size, it's not surprising that its surface would show a lot of different environments, as varied in some ways as Earth itself.

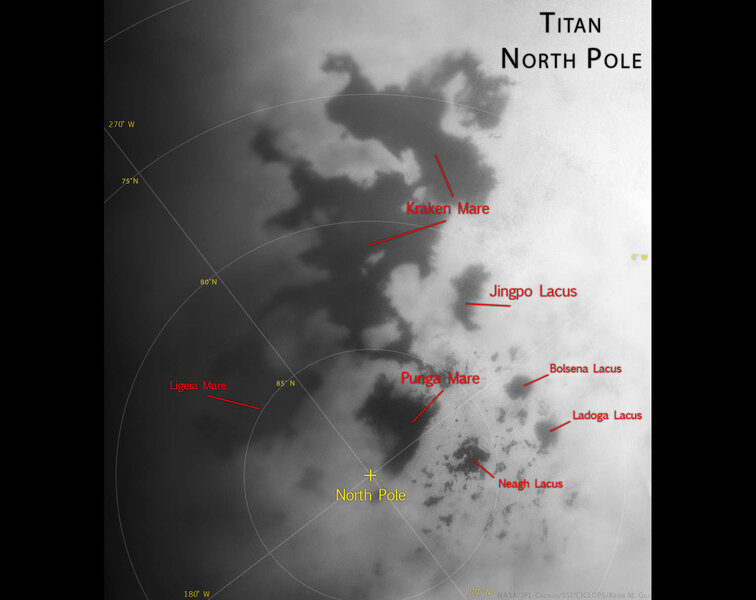

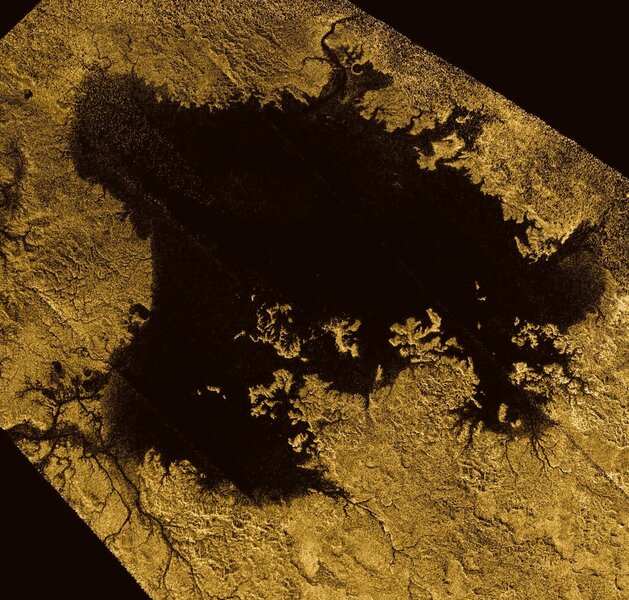

Still, there any many amazing features detected on Titan, including dunes, mountains, cryovolcanoes, and valleys, Shockingly, Titan also has dozens of huge lakes of liquid methane and ethane near its north pole! These were found by the Cassini spacecraft, which orbited Saturn for 13 years, and made many close passes of Titan. This was a huge discovery, the only body other than Earth known with open stable liquid on its surface.

Cassini also saw tributaries feeding into these lakes, indicating that the frigid moon (around -180°C) has a methane cycle like Earth's water cycle, with methane evaporating off the lakes, raining out in the highlands nearby, then flowing back into the lakes.

And now new results looking at old Cassini data have revealed another startling aspect of some of these lakes: They have rough seas. Winds and tides have stirred the liquid methane, creating waves big enough to be detected from space.

When I read this paper, I gasped out loud. I'm prejudiced, thinking Titan can't be a terribly active place when it's so far from the Sun, so cold. And yet these observations shatter my notions, showing me that I cannot let my preconceptions box in my thinking.

Wind and waves and flowing liquid on Titan, 1.4 billion kilometers from the Sun. Wow.

These conclusions come from scientists looking at infrared observations of Titan. The giant moon has a thick, hazy, atmosphere opaque to visible light, but infrared light can get through. The Sun emits infrared light, and Titan reflects it, so Cassini's Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer could be used to see down to the moon's surface.

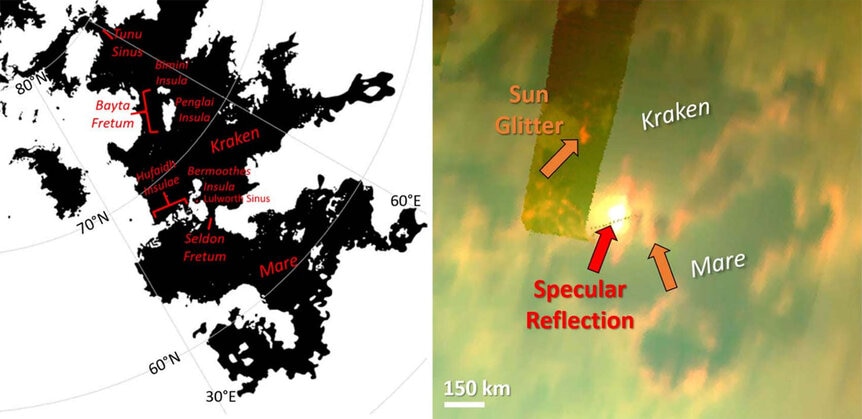

But there's more. Sunlight hitting the surface of a lake will reflect off of it, which is called a specular reflection. You may remember the old phrase from high school science, the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. In other words, if the Sun is shining down at an angle of, say, 45° on the lakes, and Cassini was on the other side of the lake at that same angle, it will see a sunglint, a brightening on that spot on the lake.

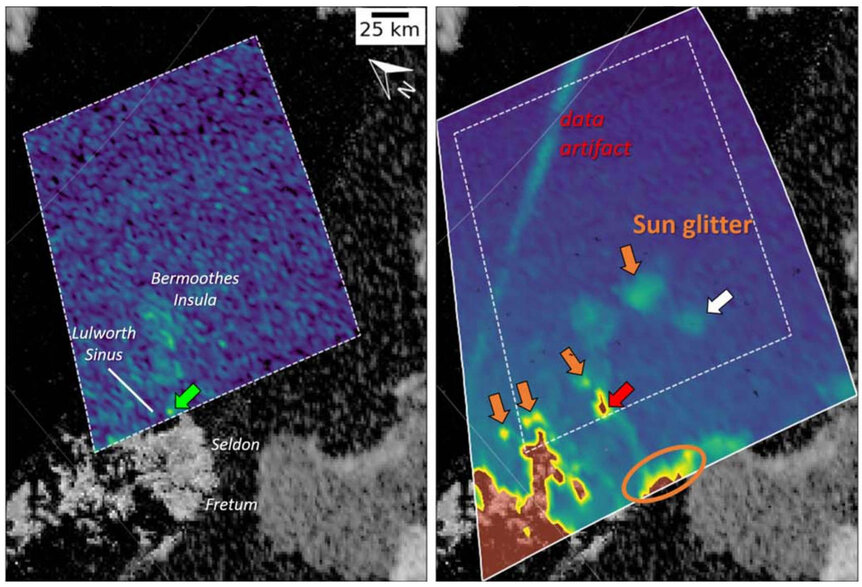

But that assume the surface of the lake is flat still. If there are irregularities in the surface — say, waves — that changes the angle of the liquid surface, changing the geometry. Instead of a flat reflection, the surface will glitter as the waves move. You've probably seen this before yourself, as ripples in the surface of a water lake on Earth appear to sparkle as they reflect sunlight.

Cassini saw precisely this in several spots on the largest lake on Titan, called — get this — Karaken Mare (mare is Latin for sea). For example, in Bayta Fretum (fretum means strait), the scientists saw Sun glitter. They interpret this as due to wind blowing across the strait, creating waves.

In three other spots (Seldon Fretum, Lulworth Sinus, and Tunu Sinus; sinus means bay), they think that Sun glitter is due to tides. Saturn is a massive planet with a large gravitational force, so the tides it exerts on Titan are pretty big. This will force liquid methane in the lakes through the straights and change the levels in the bays, creating waves as the water flows. They also see complex patterns along shorelines, similar to those seen in various places on Earth with shallow seabeds formed by sedimentation, which can create circulation patterns in the liquid surface above.

That's amazing.

The solar system is a surprising place. In some ways, Titan is so similar to Earth — a planet-sized object with a thick nitrogen atmosphere (remember, our air is mostly nitrogen too) and liquid lakes on its surface. It may also have a subsurface ocean of water, like Europa and Enceladus, heated by Saturnian tides, too. But it's hard to forget that it's an alien world, so cold at the surface that water is frozen harder than granite there, with sand made of solid hydrocarbons instead of silica and calcium carbonate like on Earth, and of course the gaudy bauble of Saturn hanging in its sky, invisible through the thick haze.

So the idea of wind whipping up frothy waves on lakes makes me think of my days spent on the shore of Lake Michigan, or in Bodega Bay near San Francisco, or any of the hundreds of lakes, ponds, and reservoirs in my own home of Colorado.

It's an alien world, certainly, but not entirely alien. I wonder how true that is for all the planets we see, for all the moons in our own solar system? What will we find on each that reminds us of home?