Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Science Behind the Fiction: Why we're afraid of Pennywise, Joker, and every other clown

If you came of age sometime in the last few decades, there's a good chance you have a certain distrust of clowns. There's something inherently creepy about them and that discomfort has only been fed and fostered by popular culture.

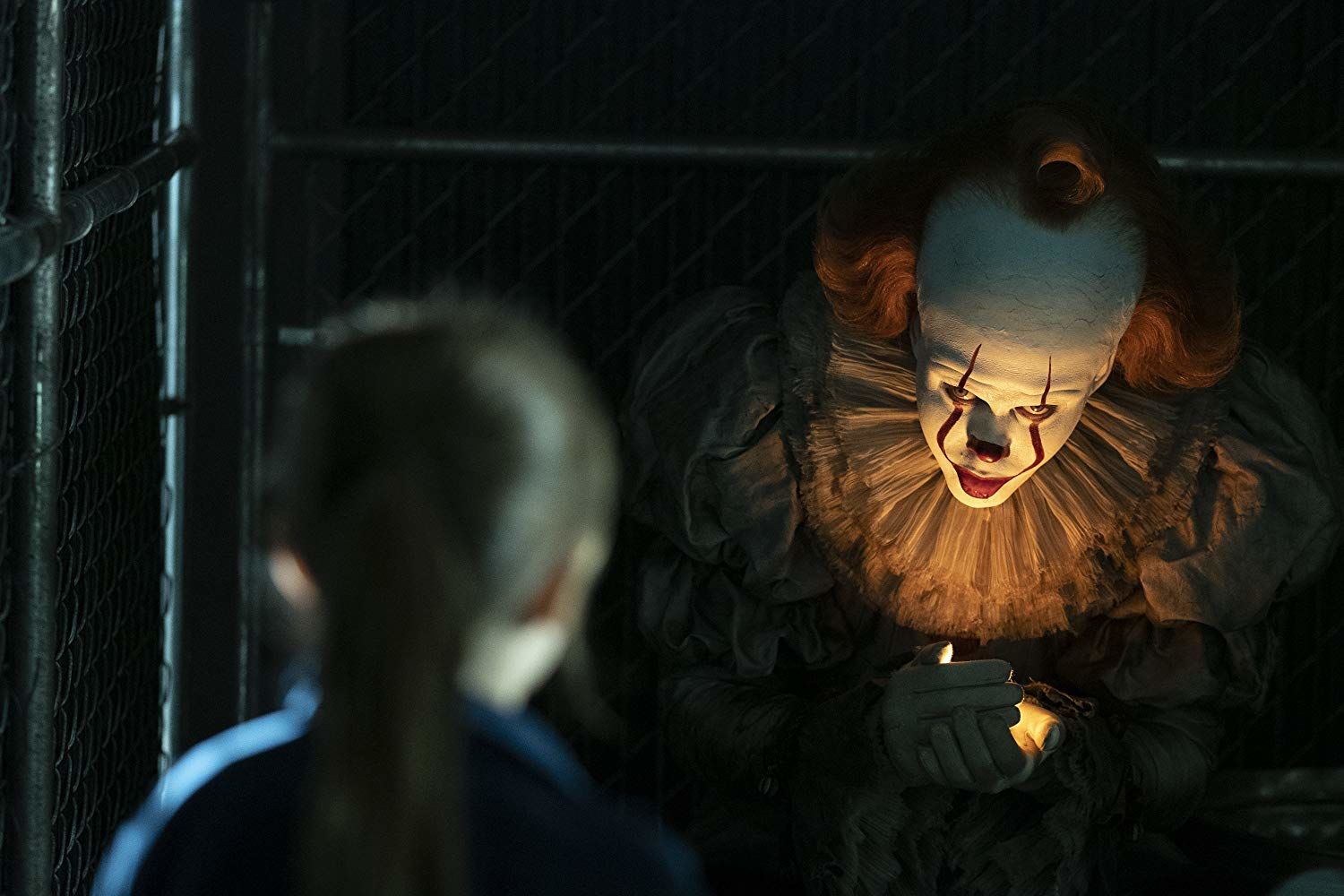

There is no shortage of frightening jesters in the annals of our books, television, and movies. The killer clowns from outer space, Twisty, and Captain Spaulding are all recognizable characters from our nightmares, but they began on VHS. And who could forget Pennywise and the Joker, both of whom have movies on the horizon in the forms of It Chapter Two and Joker?

The terrifying trouper is enjoying something of a renaissance right now, but the notion of a horrifying harlequin is hardly anything new.

THE UNCOMFORTABLE HISTORY OF CLOWNS

Clowns have been a part of modern civilization from the start, and they've existed in a state of duality all along. Nearly 5,000 years ago in Egypt, later in China and Greece, and throughout history, jesters have been a part of the royal setting and one of their major functions was to dress down the royals.

Clowns, unique among the populace, were given license to attack the throne, so long as they were entertaining. This set up an interesting dichotomy, one wherein viewers of their performances were filled with mirth and loathing in equal measure. They were able to give voice to the misgivings of the people, to say the things no one else could say.

If you've ever been present when a co-worker snaps at your boss or a childhood friend speaks out against a parent, you might have an inkling as to what it might have been like — that deep-seated discomfort when someone says or does something forbidden. There's a part of you that's sated, vindicated by the words you've longed to speak but never dared, while another part is left adrift by the recompense that never comes.

From ancient times, the very nature of clowns has been one of chaos against the established order, and it's created a relationship with those purveyors of frivolity that isn't easily defined. So, there is an underlying discomfort at their presence.

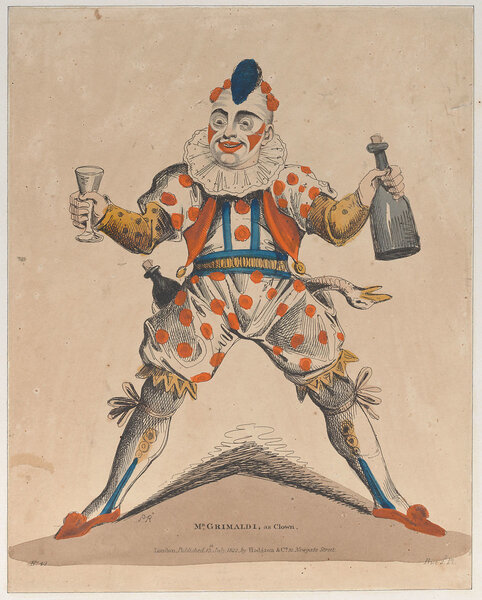

That discomfort came to a head in the 19th Century with the appearance of Joseph Grimaldi.

Grimaldi is often heralded as the prototypical modern clown. He popularized the white face paint and exaggerated features that are still the standard today. During his reign as the crown-prince of clowning, he was so well known that his personal life was the subject of considerable conversation. And that life was tragic to say the least.

Grimaldi had an unloving father, his wife died during childbirth, and that child would go on to become an alcoholic who drank himself to death at age 31. Moreover, Grimaldi's slapstick persona wreaked havoc on his body. These personal tragedies were well known, such that his character, comedic as it was, was imbued with an underlying tragedy.

When Grimaldi died, aged 48, his story might have faded from memory if not for Charles Dickens, who was charged with putting together his memoirs. The book sold well and the story of the jovial clown masking darkness remained.

Around the same time, the world was introduced to another clown who would go on to live a very different — but still dark — duality.

Jean-Gaspard Deburau made his debut in the early 1800s. He found success as a well-known performer in France. In 1836, following a particularly failed performance, he killed a boy after striking him with his cane for heckling him in the streets.

Deburau was eventually acquitted of the crime in court, but the image of the killer clown had entered the public consciousness and never totally went away.

A century later, Emmett Kelly would join the circus. He originally performed as a trapeze artist, but what Kelly really wanted was to be a clown. He created a character, Weary Willie, based on sketches he had made. He integrated the now-standard exaggerated makeup with a five-o-clock shadow, but his idea of a "hobo-clown" was rejected. That is, until the Depression hit.

By that time, hobos and tramps had gained popularity and Weary Willie came into the light. While Kelly still performed stunts, as was expected, his most recognizable features were that of failure. This was most notably seen in his attempts to sweep up a spotlight after other acts.

Since antiquity, clowns have enjoyed a sort of double life, but in the 19th and 20th centuries, we saw their role evolve into something more complex and a bit more disturbing. The performative soil was primed for their final evolution into true horror.

A DEEP-SEATED FEAR

The clowns of today are almost unrecognizable when compared to the jesters of yesteryear. They share some commonalities, a sort of common ancestor, but they have evolved in such a way as to become a primal monster, almost perfected to generate fear.

Gone are the old comedians with their funny hats; they have been replaced with painted faces, grotesque features, and oversized shoes. Any semblance of humanity has been erased, leaving only a trace of recognition.

While the stories and legends certainly feed into our fear, a long-running meme centuries old, there's something more insidious going on, and it's happening inside our minds.

It's something you might have encountered over the past decade or so, the slow progression of our fiction toward reality.

Have you ever wondered why a lifelike prosthetic is somehow more disconcerting than one made of metal? Or why the animation in The Polar Express just didn't quite sit right with you. It's because both are approaching the uncanny valley, a space between the artificial and the real which invokes a negative emotional response.

It seems, for one reason or another, that we are willing to accept things that are wholly artificial, and things that are real, but not things that blend the two. It's why those images of photo-realistic cartoon characters can be so disturbing.

A 2008 study of children showed that clowns were almost universally disliked. Additionally, even in adults, clowning took the crown at the top of a list of creepy occupations. While understanding the mechanics of the mind is an intrinsically difficult prospect, it's thought that the reason for the participants' discomfort is related to the uncanny nature of clowns. They approach what we know as ordinary but don't quite make it. Their facial features and mannerisms are almost ordinary, but not quite, and that unsettles us in a way we can't always explain.

These factors — the uncomfortable nature of clowns, combined with the societal narrative built over thousands of years — results in a conclusion that's difficult to combat. All of this is solidified by a change in the ways we engage with clowns.

People no longer flock to the big top the way they once did, where clown could be seen as innocent, if unusual, entertainers. Now we spend our time in front of screens, both big and small, where clowns are primarily seen as villains. And there's no sign that this metamorphosis is stopping. In all likelihood, before long, clowns will no longer have a place at the birthday table, relegated to their final resting place in the halls of horror. Maybe that's where they properly belong.