Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Turns out Mars' Jezero crater really was a lake, says Perseverance evidence

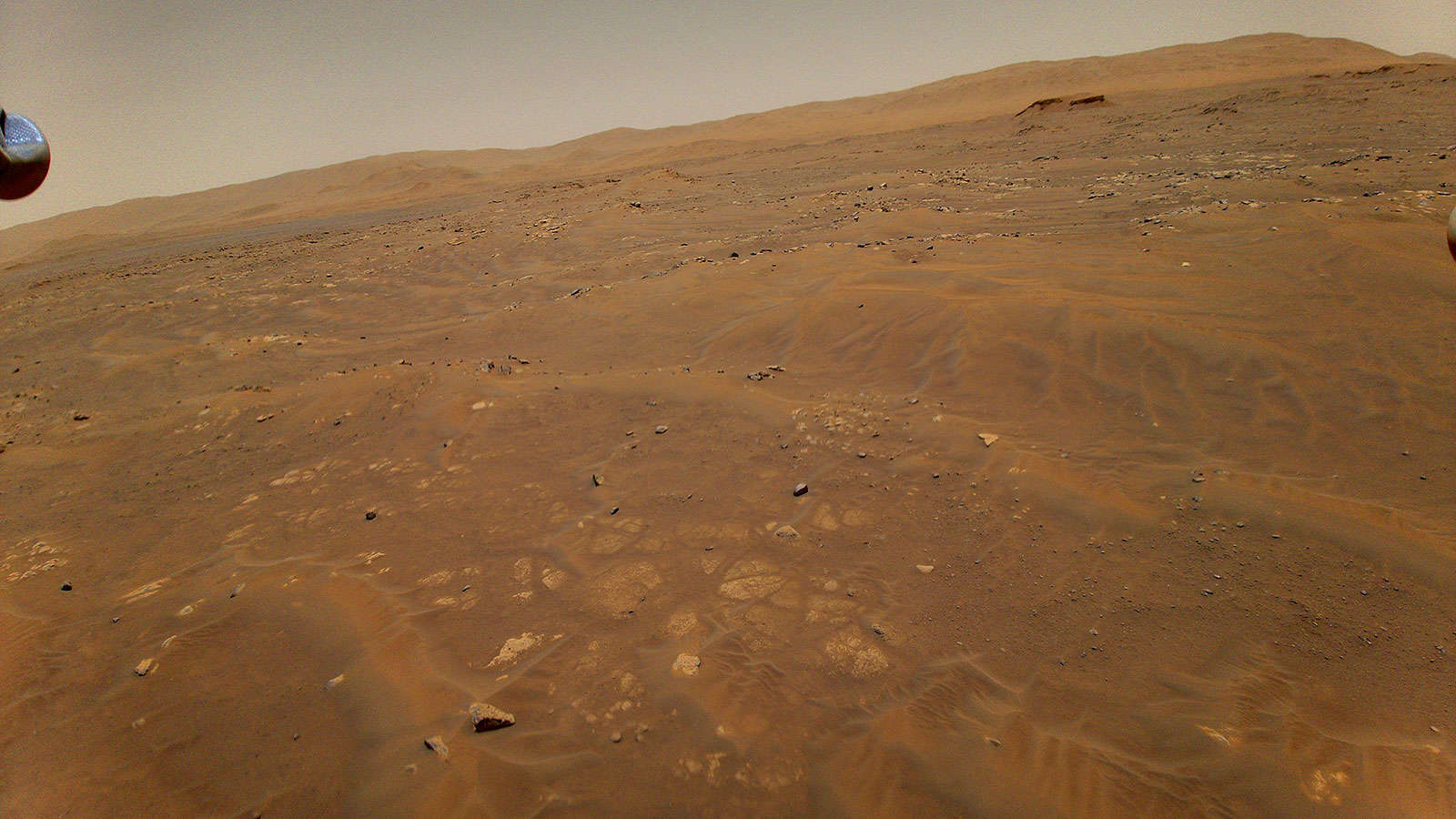

Before Perseverance landed in Jezero crater, there was one Mars question (besides whether there was ever life on Mars) that really needed an answer. Was that crater ever a lake?

While Jezero Crater was previously thought to be a lake, there had been no way to confirm it until researcher Benjamin Weiss of MIT and his team analyzed images that Perseverance beamed back to Earth. Turns out it really was a crater lake once. Mars may now be a frozen, barren wasteland, but billions of years ago, it was probably closer to Earth than the hell planet it is now. Jezero brings us that much closer to finding out if it was ever inhabited by anything.

Weiss led a study that was recently published in Science, unearthing all the proof that the parched crater Perseverance is crawling through was once a lake that life, at least as we know it, could have survived in.

“The key observations from the rover that established that Jezero contained a lake billions of years ago were images showing tilted layers of rock with mostly fine grains,” Weiss told SYFY WIRE. “The occasional presence of larger grains means that water was required for the deposition of these tilted rocks—they could not have formed as sand dunes.”

The tilted structures Weiss observed in the rover’s images are analogous to beds of sediment on Earth. Most smaller grains found in the crater were similar to sand grains, while the larger ones were closer in size to pebbles and cobblestones. What is even more amazing is that Perseverance didn’t even move during the first three months of its stay on the Red Planet. Its Mastcam-Z and SuperCam Remote Micro-Imager (RMI) cameras imaged as much of the region as they possibly could. Looking at the main outcrop and Kodiak Butte, it saw what were once tilted sediment beds that had since morphed into rock.

Jezero Crater’s main outcrop is fan-shaped, a giveaway that it was once a river delta. Kodiak butte is a smaller rocky outcrop that Weiss’s team believes was part of the delta but may not appear that way now because of erosion. Meaning, not only was Jezero Crater a lake, but that lake was fed by a river that carried sediment and rocks over. Hi-res images of Kodiak butte showed closeups of sediment whose dimensions could then be measured to be sure that it was water and not wind that brought the rocks and sediment there to begin with. Perseverance had stayed still for all the time it captured these shots.

There are also boulders in the crater, which were evidence for flash flooding. Sediment takes nearly no effort for water to sweep it from one place to another. Hunks of rock up to three feet wide couldn’t have been carried to the lake unless they were hauled there by water moving ridiculously fast.

“We expect that the top of the delta formed after everything below it. Because the top also has the largest grains (boulders), this suggests that the youngest flows were floods, unlike the more gentle earlier conditions,” said Weiss. “This flood could be from a change to a colder climate.”

If there was a shift in climate, from lush and warm to a bitter chill, ice deposits could have formed on the rim of the crater. If temperatures shot up again and the ice melted, there could have been a potentially catastrophic flood from water being released downstream, but the hypothetical flood could have also happened from a random shift in the source of the lake’s water. This is where the rocks have to speak for themselves.

Weiss thinks that zooming in closer to the boulders could possibly tell us which of these scenarios actually happened. What he wants to find out even more is whether the water in the lake could have been swarming with microbial life-forms. Why Mars lost its atmosphere has been long debated, and though the loss of its magnetic field was probably what left the atmosphere unprotected and susceptible to being decimated by solar storms and cosmic rays, among others things, the answer still eludes us.

“When this magnetic field died, the atmosphere could then have been stripped away by the solar wind, a hypersonic plasma shooting out from the Sun in all directions,” he said. “We want to test this idea by measuring records of the past Martian field recorded in rock samples that formed at different times.”

While the samples that Perseverance is now digging for may ultimately tell us if anything was ever alive in what is now an expanse of red dust, we will have to wait for the sample return mission to find out.