Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

How Star Trek's Prime Directive is influencing real-time space law

Michelle Hanlon moved around a lot while growing up. Her parents were part of the Foreign Service, the government agency that formulates and enacts U.S. policy abroad, so she found herself in new places all the time. Despite relocating often, one memory of her childhood remains constant. "We always had Star Trek," Hanlon tells SYFY WIRE. "You know how families have dinner around the table? I remember eating meals in front of Star Trek, watching it no matter where we were."

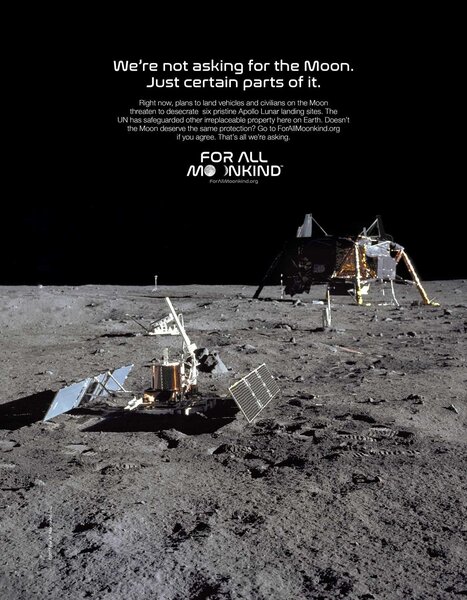

That connection to Star Trek, in part, inspired Hanlon to create For All Moonkind, a volunteer non-profit with the goal of preserving the Apollo landing sites on the Moon, alongside promoting the general preservation of history and heritage in outer space.

Hanlon, who is a career attorney, has always had an interest in outer space. She didn't study engineering or other sciences while at school, though, so she felt it couldn't be more than a hobby. But after Johann-Dietrich Wörner, the head of the European Space Agency, made an offhand joke about how China may remove the United State's flag from the Apollo moon landing site during a press conference, Hanlon started thinking about space preservation and what would eventually become For All Moonkind. She started the group in 2017 with her husband after returning to school to get a master's degree in space law.

One point Hanlon and For All Moonkind stress is the idea that we can only preserve our history in space if we put the space race behind us and do it together — an ideal partially inspired by Star Trek. "I've never felt that I couldn't do what I wanted because of my gender or race because I grew up with Star Trek," Hanlon, who has a Polish father and Chinese mother, says. "The diversity [in] Star Trek was a reflection of my life; I was shocked to not see it when I came back to the U.S."

Hanlon especially looks up to George Takei, who was one of the first Asian actors to play a heroic character on TV as Star Trek's Lieutenant Hikaru Sulu. And she remembers the story of how Martin Luther King Jr. convinced Nichelle Nichols to remain on Star Trek after the actress wanted to leave her role as Communication Officer Lieutenant Uhura. Both are examples of Stark Trek as a progressive melting pot. Stories like those, and the overall diversity of the cast, helped shape her worldview.

That same mindset, where diversity and cooperation will be the only way we'll get further in outer space, has seeped into her work with For All Moonkind. The organization helped get the One Small Step to Protect Human Heritage in Space Act — a law that would see "all U.S. government licenses related to space include requirements preserving the Apollo landing sites" — passed in the Senate in July 2019. The bill is currently waiting to go through the House of Representatives, although both Hanlon and other space experts believe it's not a high priority for lawmakers with the election underway.

Hanlon and other volunteers are also working with international governments and organizations to pass a resolution through the United Nations. "We keep reaching people and getting positive feedback, we've gotten a lot of informal support," she says. "People keep saying come back. We count that as a win."

Convincing international governments and groups is one of the primary obstacles For All Moonkind faces in its path to preserving parts of our history in the United States. "If it's framed as something that's overseen or controlled by the U.S., then it'll be a problem," Ram Jakhu, an associate professor of law at McGill University and a space law expert, explains.

Additionally, For All Moonkind is pushing governments to think about what it means to own property in outer space. The Outer Space Treaty act in 1967 prohibited "any government or international entity from claiming property on the moon." It's something that most governments haven't considered due to it "not being a big priority," Hanlon says. "Everyone thinks they have so much time, but it's really around the corner."

"The moon is going to be very crowded soon," she adds, emphasizing that we're going to miss our chance at preservation if we don't take action immediately.

The United Nations is currently focused on the impact of orbital debris, but For All Moonkind is leading the conversation about preservation.

"The real question when you talk about the moon is property," Hanlon says. "You can't own property on the moon." The Outer Space Treaty prohibits any government from claiming property on the moon, and despite growing plans to return to the Moon (and even Mars by 2022) governments have yet to consider what property ownership might look like in space.

While Hanlon and other For All Moonkind volunteers urge governments and space groups from around the world to act, they are trying to spread awareness and approach the problem from other angles. For instance, they're currently compiling an interactive database of all the Apollo landing sites and objects on the moon. They plan to build a site so visitors can learn more about the Apollo missions and For All Moonkind's preservation mission. They don't have a confirmed release date for the site yet.

Over the past 20 years, space exploration has changed from a mostly private endeavor to something that private companies can take part in. It's a big shift from space exploration's origin in the Cold War. "We initially went into space as part of an international competition that was driven by national pride and security," said Robert Pearlman, another For All Moonkind board member and the founder of collectSPACE. But now that there isn't a race to colonize the moon or land a person on Mars first, people such as Pearlman and Hanlon believe space exploration is something that needs to be completed together, cooperatively and not competitively.

For All Moonkind is leading the charge in trying to unite groups from all over the world so they can complete their mission to preserve part of our history in space. They still have a ways to go, but they have no plans to stop. Star Trek, with all of its sci-fi glory, is a small part of how they got to where they are today.

"Star Trek is an inspiration, from a regulatory standpoint," Pearlman says. "The Prime Directive, where you do no harm, is the way we approach the idea that the solar system doesn't belong to anyone. The flag we planted wasn't a symbol that we own it, just that we were there."