Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Star Trek vs. Red Dwarf: The Battle of Wolf 359

On Stardate 44002.3, the Federation was handed its worst defeat since the Battle of the Binary Stars that set off the first Klingon War — and despite a hellacious and damn-the-photon-torpedoes fight, the Borg easily wiped out 39 starships, leaving nothing between them and Earth.

Well, except for the Enterprise, and Data, and really bad security software coding in the Borg back systems.

The location of that battle was the star Wolf 359, and the date, in the old non-relativistic pre-warp Earth calendar, was (is? Will be?) June 6, 2366.

The Battle of Wolf 359 was good for only two things: 1) It delayed the Borg enough to allow the Enterprise to stop them from assimilating Earth, and b) it gives me a chance to tell you about a really cool star. Literally: Wolf 359 is a dinky red dwarf.

Why now? Well, today is the -347th anniversary of the battle, so what better time to talk about it?

In "Best of Both Worlds," the episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation where the Borg came within minutes of infesting Earth with green nanites, we unfortunately didn't get to see the action at Wolf 359; by the time Enterprise gets there the day was already lost. We don't even get a glimpse of the star itself*.

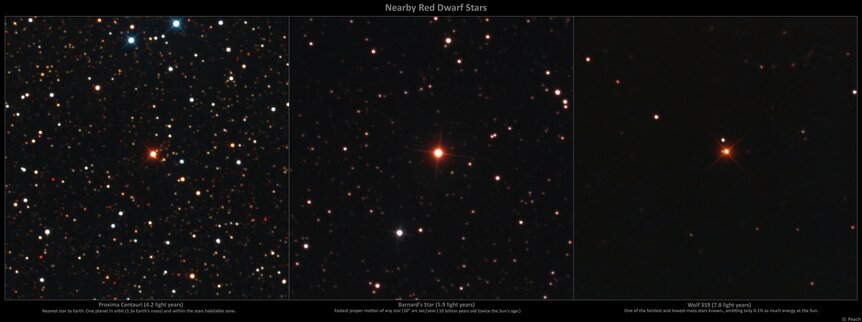

That's too bad. Wolf 359 is beautiful. I can prove it, too, with the help of master astrophotographer Damian Peach:

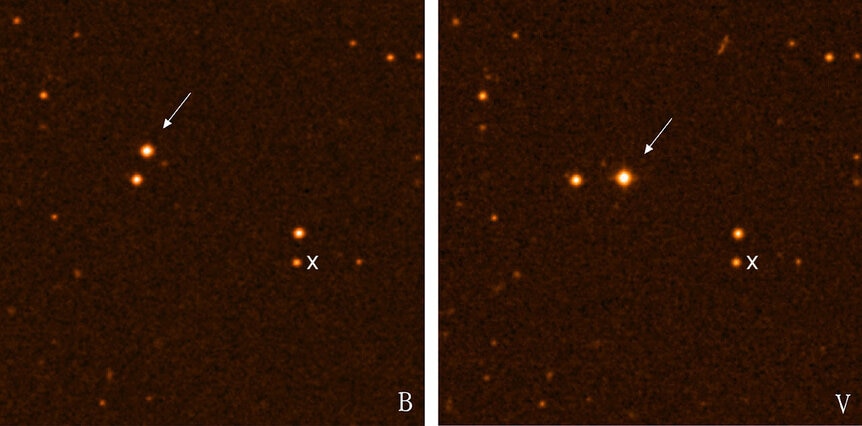

Wow. That's a really red star. Peach took this image using a 0.7-meter CDK700 PlaneWave telescope located under the very dark skies of Siding Spring, Australia (that sound you hear is me drooling uncontrollably; that's a nice 'scope). It's natural color — he used a red, green, and blue filter to take three separate exposures of five minutes each and combined them to create the image. Given the nature of the star, he almost needn't have bothered with the blue filter.

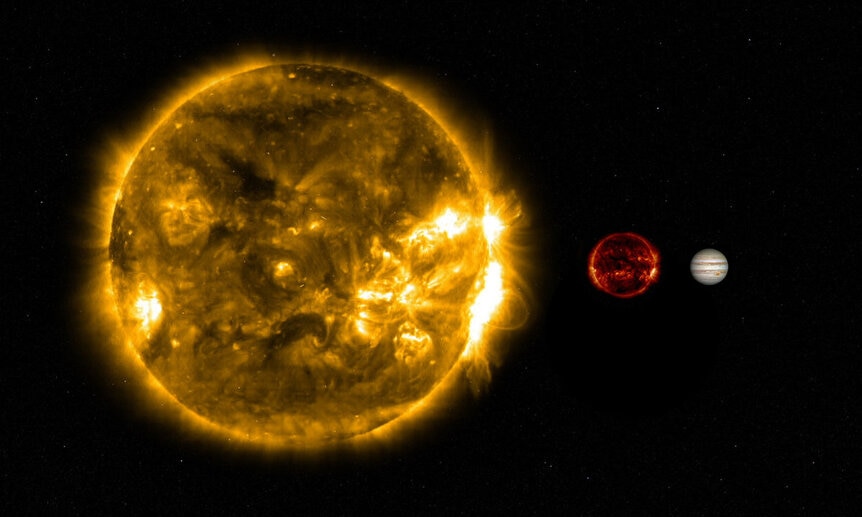

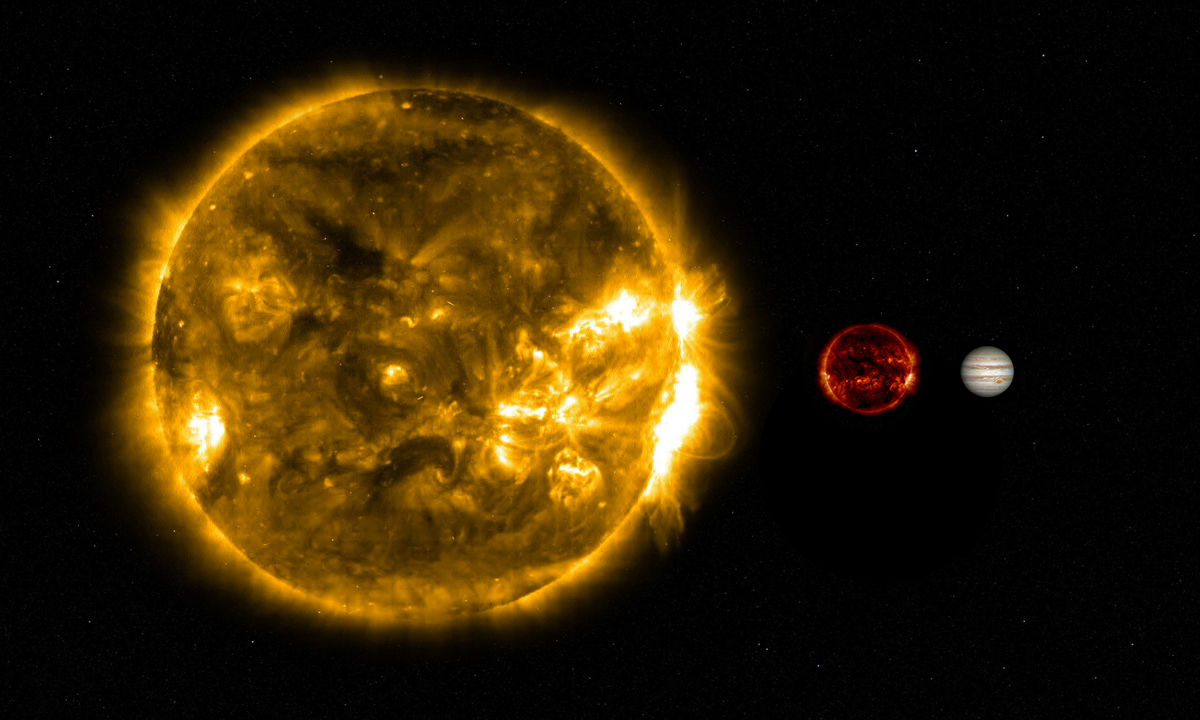

That's because Wolf 359 is a very red star. It's a red dwarf, smaller and cooler than the Sun. It only has about 10% of the Sun's mass, and about 1/6th its radius, making it not even twice the diameter of Jupiter! It's not the smallest star ever seen, but it's truly a wee little thing.

The brightness of a star depends on its temperature — hotter stars emit more light per square centimeter — and its size — more area means more light emitted. Wolf 359 is damned on both ends of this, so small and cool it's intrinsically very dim: It only emits 1/1000th the amount of light the Sun does! And most of that is in the infrared; in visible light (the light we can see) that fraction drops by a factor of 50.

That's incredibly dim. Replace the Sun with Wolf 359 and it would only appear to be about 8 times brighter than the full Moon! You could read by it, but not easily.

If you want to see Wolf 359 for yourself, well, good luck. It's in the constellation of Leo, and shines at a meager magnitude of 13.53 — the faintest star you can see with your naked eye is a thousand times brighter! That's pretty amazing, considering it's one of the closest stars to the Sun, at a distance of just under 8 light years (which is why it was picked to be the location of the last stand against the Borg).

Think of it this way: Wolf 359 is the fifth closest star to the Sun (including all three stars in the Alpha Centauri system) in the Universe, yet you need a pretty good telescope to see it at all. Happily, Peach did, and got that lovely photo.

And when I said it's cool, and I meant it literally. With a surface temperature of 2,500°C it's only about half as hot as the Sun. You wouldn't want to stand on it or anything, but for a star that's lukewarm at best.

It's so cool that actual molecules can survive in its atmosphere; for stars like the Sun that doesn't happen. But things like carbon monoxide and iron hydride have been detected, and even water! Well, steam.

But have a care here. Just because it's small, low mass, and chilly as stars go, doesn't mean it can't be feisty. Because oh yeah, it can throw a tantrum.

Stars as low mass as Wolf 359 have a weird property: They're fully convective. In stars like the Sun, there are three main layers. The core is where hydrogen fuses into helium, making energy. That energy is transported away from the core radiatively; that is, literally through radiating light. This hits the gas above it and heats it up, which responds by emitting light and heating up the stuff above it. The layer where this occurs is called the radiative layer. At some distance above the core the density of the gas drops to a certain limit, and at that point it starts to rise via convection. That's where hot stuff is less dense than material around it so it rises, cools, and sinks back down. The Sun's convection layer reaches all the way to the surface.

But red dwarfs aren't like that. Their convection zones start right above the core, so the gas moves a long way from the interior to the surface. That's important because that gas has a strong magnetic field tied up in it, stronger even than the Sun's. When these magnetic field lines reach the surface they get tangled up, and they can snap, releasing a lot of energy. Like a lot a lot.

These are called stellar flares, and they generate vast amounts of high-energy X-rays and gamma rays. Wolf 359 has been seen to blast these out many times per hour. The flares are less energetic than the Sun's, but they happen all the time. A planet orbiting Wolf 359 would be a not so great place to hang out.

The TNG episode didn't mention planets around the star, which may be for the best. But I wonder… Federation starships have astrometrics labs. I wonder if any astronomers in the lower decks were desperately trying to tell their captain to lure the cube closer to the star, right over that huge sunspot they had scanned earlier. Then it's just a matter of time… a good flare from Wolf 359 can emit as much energy as a hundred thousand one-megaton bombs. Bye-bye Borg cube (note: This exact (and I do mean exact) premise was used in the seventh season TNG episode "Descent, Part II").

Incidentally, an episode of the old Outer Limits used the star in one episode. I rewatched that too, and the overall plot was, um, interesting, in that they create a miniature version of a planet orbiting Wolf 359 in a lab and allow evolution to run on it, which of course it does superfast because… it's small. Right. And then the spirit of the planet starts to attack the scientist and his wife destroys the planet with a chair, and did I say the plot is "interesting"? Because that show scared the crap out of me when I was little, but watching it now is a very different story.

But the science of the actual star itself is still cool, and the TNG episode was pretty dang good, too. So, with Wolf 359, you really do get the best of both worlds.

*Rewatching the episode, I thought for a moment the star was shown, but the dull orange glow turns out to be from a destroyed starship.