Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

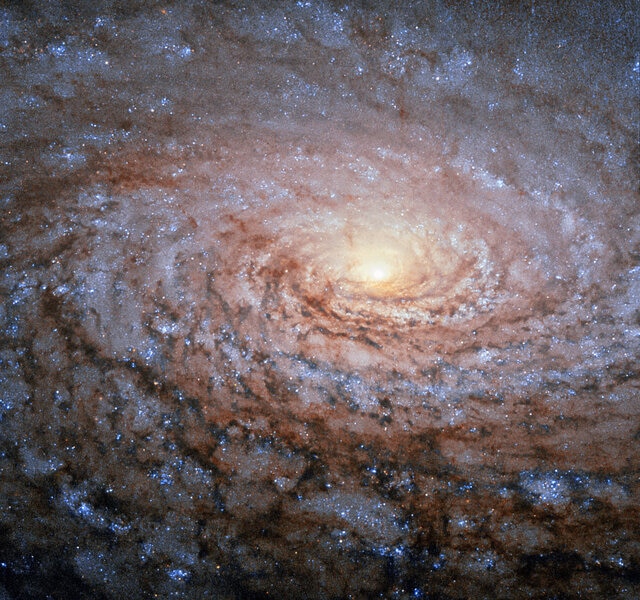

The spectacular Sunflower Galaxy M63

Sometimes, you just need a gorgeous picture of a spiral galaxy.

I'm here to help. Feast your eyes on the magnificence of M63:

Whoaaaaa. This image is composed of observations taken by Hubble Space Telescope, the Subaru telescope, and Don Goldman. It was processed by Robert Gendler, Roberto Colombari, and Goldman (you can get a bigger version here).

M63 is also called the Sunflower Galaxy, and in this image I can see why; the spiral arms wind in toward the center and are patchy, like the seeds in the head of a sunflower. The clumpy nature of the arms is relatively common in spirals, and we call them flocculent, which means composed of tufts like fluffy wool or cotton balls. Two other wonderful examples of this are NGC 2841 and NGC 3521.

The patchwork nature may be due to a process called (and I love this) stochastic self-propagating star formation. If a gas cloud is forming stars, then the big, hot stars born there can trigger star formation in nearby gas clouds, and then the stars born there trigger stars in other nearby clouds, and so on. As the galaxy rotates those clouds are sheared away from each other, creating the blotchy spiral pattern. It's not certain this is the process, but it does explain a lot of what we see. The patchiness goes all the way in to the center, too, and the overall spiral structure stands out when an infrared telescope like Spitzer is used to observe it.

M63 is pretty close as galaxies go, about 25 million light years away — I've seen measurements as low as 23 and as high as 27. Getting exact numbers can be difficult; after all, it's something like 250,000,000,000,000,000 kilometers from Earth! I'll forgive a few quadrillion kilometers here or there.

But on the scale of the Universe that's in our back yard, and that means it's a relatively bright object*. You can spot it with binoculars as a fuzzy patch, and its structure starts to become more clear with larger telescopes. It's just off the end of the handle of the Big Dipper, and is high up in the sky for northern observers in the late spring. I may have to take out my ‘scope and give it a look; it's near M51 (yeah, trust me, click that), another wonderful spiral, and from a dark site should be pretty nice.

In fact, M63 and M51 are at roughly the same distance, and their proximity in the sky implies they are physically near each other as well. There are a handful of other galaxies there as well, and astronomers think they are indeed associated with each other, so we call this the M51 group.

Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is a member of what we call the Local Group, a collection of a few dozen small galaxies (we're the biggest, together with the Andromeda Galaxy). I imagine from M63 our own group would be quite a sight; from its location the Milky Way would be face-on, and they would see our whole spectacular spiral structure even better than we see its!

I personally think faster than light travel is impossible, but that doesn't mean I wish it weren't. I'd love to see our galaxy splayed out across the sky, its structure exposed and obvious. What a sight that would be.

*The name gives that away too. The M stands for Messier (MEZ-ee-air), as in Charles Messier, a French astronomer and comet hunter who got annoyed that he kept seeing fuzzy objects in his telescope that looked like comets. He made a catalog of them, and those 100 or so objects are the brightest and now the most celebrated things to see in small telescopes.