Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The weird sisters of Shakespeare and the witchcraft trials of his time

"When shall we three meet again? In thunder, lightning, or in rain?"

These are the opening lines to Macbeth, one of William Shakespeare's most beloved and iconic plays. This tragedy of vaulting ambition and dirty politics has been shrouded in myth and superstition for centuries. Many people in the drama world believe that the play is cursed and will not refer to it by title but rather "The Scottish Play." Some theaters even commit to supposed cleansing rituals to ensure that their performance is not plagued by misfortune. Legend claims that real witches from the Bard's time were so incensed by his use of supposedly real spells in his play that they cursed Macbeth to be forever unlucky or even outright fatal. Never mind that, statistically speaking, more actors have actually died during productions of Hamlet than Macbeth over the centuries. Witches are just scarier than ghosts. Sorry, Hamlet.

The weird sisters of Macbeth are certainly an unnerving lot: a trio of strange women whose omniscience drives the seemingly benign Lord Macbeth, the Thane of Glamis, and his wife to ruin as they murder their way to the throne of Scotland then find themselves ravaged by unbearable guilt. Influenced by Greek mythology and British folklore, the witches are typically depicted as evidently evil crones whose prophecies inspire chaos and degradation. Double, double toil and trouble.

Their intentions are clearly anything but good, even as they do very little to drive Macbeth and his wife to act. They never instruct him to kill his rival. It's easier to just tempt him with the possibilities of what he could have if he just stabbed his rival a few times. In a play with endless bloodshed and one of Shakespeare's greatest villainesses, it's still the witches who seem to elicit the most fascinating responses.

This was deliberate on Shakespeare's part. He always wrote plays for the general public and his royal patrons. By 1603, he had a new monarch to amuse in the form of King James VI of Scotland and I of England. The Jacobean era had begun and if there's anything a writer knows best, it's to keep the man with the power to behead you on your good side. James had one big interest in his life: getting rid of witches. He hated witchcraft and dedicated much of his adult life to its study and the persecution of its accused practitioners. James often supervised the torture of women accused of being witches. He even wrote a book about it called Daemonologie. While it was said that his zealous hatred of witchcraft waned in his later years, his reign as King of England was still defined extensively by it. Shakespeare certainly knew enough about it to want to please his new King with a play about how much witches suck and try to ruin the lives of good monarchs.

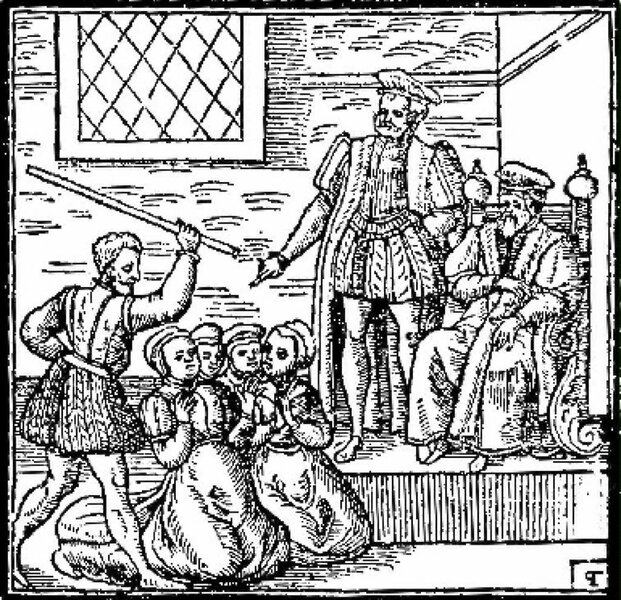

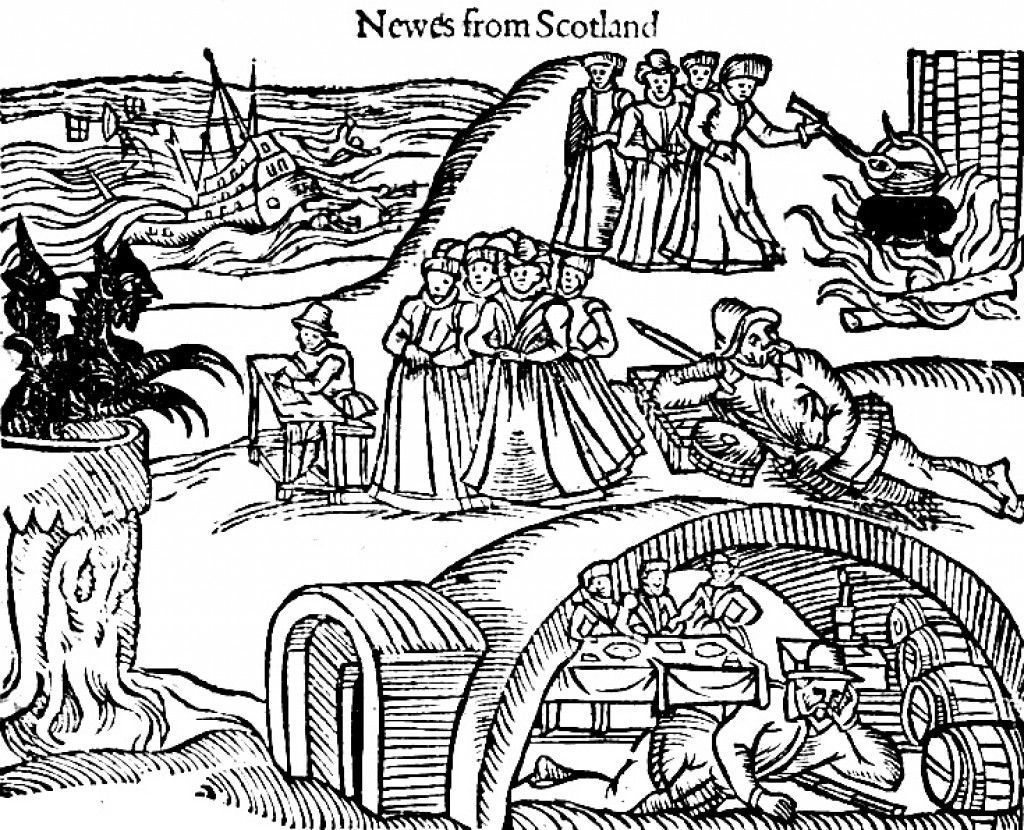

The first major witchcraft persecution in Scotland happened in 1590 with the North Berwick trials. James had been inspired after a trip to Copenhagen to marry Princess Anne of Denmark was hampered by bad storms and the admiral of the Danish fleet blamed the wife of a high official for cursing the voyage. The ensuing trials, which led to the burning of two women, was so inspiring to James that he decided to bring this new fad to Scotland and the North Berwick trials proved to be the perfect testing ground for his obsession. Men and women alike were accused of witchcraft during this trial, but the defining images from this event are of women kneeling before the King as a man looms overhead with a stick to beat them.

One of those women was Agnes Sampson, a local elderly woman who was highly respected in her community. Sampson was one of many people accused by Gillis Duncan, a maid who confessed to witchcraft after extensive torture and named names quickly as a result. Like many, Sampson denied the claims and didn't "confess" until she was tortured. This was described in a news report from the time (the translation from Old Scots comes courtesy of Wikipedia):

"Therefore by special commandment this Agnes Sampson had all her hair shaven off, in each part of her body, and her head thrown with a rope according to the custom of that Country, being a pain most grievous, which she continued almost an hour, during which time she would not confess anything until the Devils mark was found upon her privates, then she immediately confessed whatsoever was demanded of her, and justifying those persons aforesaid to be notorious witches."

During her torture sessions, Sampson was also fastened to the wall by a device known as a witch's bridle, which forced the victim's mouth open with sharp iron prongs against the tongue and cheeks. Other accused witches had their fingernails torn off and iron pins shoved into the delicate skin. Sampson was garrotted and burnt at the stake on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh on January 28, 1591.

Sampson was but one of potentially thousands of people accused of witchcraft during James’ reign and she is representative of the prevalent image that was pushed at the time of what a witch looked like: an elderly woman alone in her community, often widowed or a spinster, typically poor or a beggar. As is still dishearteningly the case today, the most maligned women in society were the favored targets for such attacks. Over 75% of reported witches from this time were women. Of course, it's unlikely that any of the accused witches were actually witches. Wouldn't you admit to being something you weren't if your fingernails had been ripped off? Many women accused of witchcraft were simply women who were deemed unruly or "weird" by society. Scholar Thomas Lolis speculated that James' goal with such targeting of women was done to distract attention away from the gathering of men among the societal elites; divert suspicion away from the true machinations of power and plotting and get people to panic over female communities instead.

Macbeth's witches are most definitely witches, and they represent a veritable full house of clichés and contemporary fears about such creatures. The fear they evoke is less through active meddling in the dark forces and more through the ways that they mentally poison their targets. All they have to do to Macbeth is tell him that he'll be King one day and his path to ruin is set. They never tell him to kill the current King. He does that all on his own but the blame still lies with the witches. They are ugly, spiteful creatures who lash out at people for petty reasons and use body parts and animals in their spells. Whereas Macbeth is a tragic hero, the witches are just tragic. The message is clear: "good" people don't use magic. We see this in other Shakespeare plays, such as The Tempest, where Prospero cannot return to polite society until he casts off his sorcerer powers.

British Parliament wouldn't repeal the Witchcraft Act of 1563 until 173 years later. By that point in time, Brits were increasingly skeptical of the existence of witchcraft, and the removal of torture as a legal means of extracting confessions shockingly made it harder to get women to confess to witchcraft. The idea of witchcraft prevails to this day and even Shakespeare's weird sisters seem less malicious with fresher eyes. New productions of the play often depict them as stand-ins for contemporary societal outcasts, less malicious forces in the grand scheme of political back-stabbing. In these takes, Macbeth is the master of his own fate, an already callous and scheming figure who uses the witches' prophecies as an excuse to do what he's always wanted to. 21st-century politics hardly needs the input of maligned women to inspire irrevocable rot, after all.

To this day, it is said that the naked ghost of Bald Agnes haunts the grounds of Holyrood Palace, one of the official residences of the British royal family. She limps in agony through the halls in a state of perpetual torment, a reminder to the elite of the modern day of what happens when the power of women is misjudged.