Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

To Map a Thousand Million Stars

Our Milky Way galaxy is a huge place: It has something like 200 billion stars in it. When you go out on the darkest night imaginable and look up, it seems like the sky is filled with stars, but in reality you can only see a few thousand at most. That’s a paltry figure compared with what’s really out there.

Over the years telescopes have mapped many more stars; the Hubble Space Telescope has a catalog that contains tens of millions of them. But even that is just scratching the surface.

The European Space Agency is fixing to change all that. In 2013 it launched the Gaia observatory. Its mission: Map the positions and characteristics of more than a billion stars and other objects in space. A billion. With a B.

It’s an unusual mission. Normally different cameras would be used to perform the different tasks, but Gaia puts them all into one instrument. And its accuracy is amazing: It will have a stunning resolution of 24 microarcseconds (an arcsecond is 1/3,600th of a degree; the full Moon is about 1,800 arcseconds across).* That’s equivalent to seeing a cellphone sitting on the Moon and is several thousand times sharper than Hubble can do!

Gaia will also measure the change in positions of the stars as they move around the galaxy, as well as their apparent motion as the Earth moves around the Sun (called parallax). All this information can be combined to get far more accurate distances to stars than has ever been achieved before.

On top of that, it will also take spectra of the stars, breaking their light up into colors, which allows astronomers to determine what kind of stars they are, how hot they are, and more. Finally, it will also use very fine measurements to find the motions of the stars toward and away from us (using the Doppler shift) that will nail down their precise motion through space.

Let me ask you: Do you have a phone camera? If so, it probably has a few million pixels in it, allowing you to take nice, hi-res pictures. But don’t get too cocky about it: Gaia’s camera has nearly a billion pixels! Yes, it’s actually a 1,000 megapixel camera, which when added all together is physically a ridiculously huge 1 x 0.4 meters (40 x 16 inches) in size.

Unlike most telescopes in space, it won’t be sending gorgeous images back to us on Earth; instead, it will determine all those stellar characteristics and then return that data to us, creating a huge catalog. Even then, the amount of data will be huge; if it sent back actual images it would be impossible to store it all. It will take five years to map out the whole sky several times, and three more years to process the data.

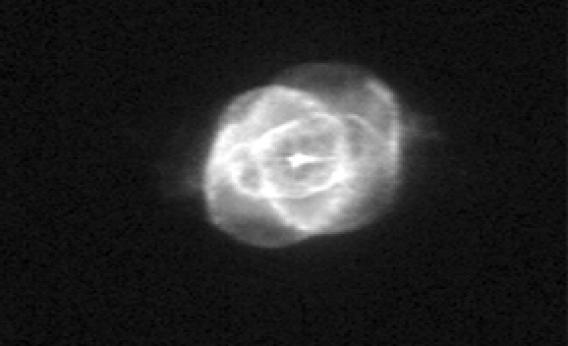

However, right now scientists and engineers are fine-tuning the telescope, making sure they understand how it’s aimed and focused. So Gaia is, for the moment, sending back some pretty cool images. At the top of this post is the Cat’s Eye nebula, a dying star about 3000 light years away (I’ve written about this object before). Here’s a shot of the star cluster NGC 1818, located in another galaxy about 200,000 light years away:

The image looks a little funny, and I found out that’s because the pixels in the camera are rectangular, not square. That’s done to match the rectangular mirrors used in the telescopes. It’s odd, but should work very well. Anyway, the image was morphed a bit, making it look nicer. Incidentally, the image of the cluster only occupied about 1 percent of Gaia’s total field of view. This observatory really is a monster.

And it will revolutionize galactic astronomy. With this much information at their fingertips, astronomers will understand the Milky Way better than ever. And more than that, too; Gaia will see asteroids, gas clouds, and far more distant galaxies, too. While it won’t give us images, it will provide a vast treasure trove of data that will be tapped by scientists for decades. And since the stars are all in motion, it will provide a baseline for future missions as well.

The geek in me can’t help but think that this is the first step in having something like Star Trek’s astrometry lab. A billion stars … who knows? Maybe someday this data will be used by some future explorer, mapped out, and used as a navigation tool. That would be a future I’d very much like to see.

*Correction, Feb. 17, 2014: This post originally misstated the width of an arcsecond.