Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

To search for the one-armed spiral…

When you look at most spiral galaxies, they show an amazing symmetry in their bright structure, with huge arms sweeping around them on either side.

But that's not always the case. Some spirals show a remarkable asymmetry, sometimes only having one arm, or with one major arm and several smaller ones. A lot of times these off-kilter galaxies are dwarf galaxies, smaller than your average spiral. These are called Magellanic spiral galaxies, named after the prototype, the Large Magellanic Cloud, a mostly irregular small galaxy that orbits our Milky Way. The LMC shows hints of spiral structure, which may have been stronger in the past but got disrupted by the immense gravity of our home galaxy.

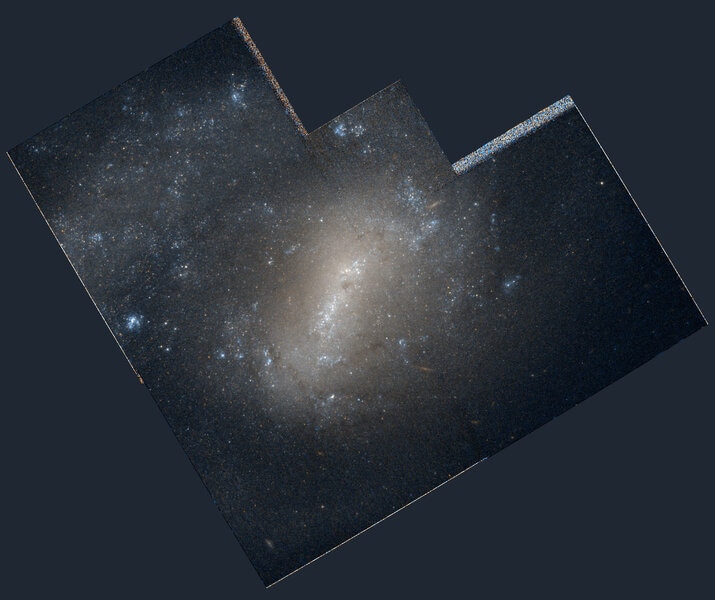

Another great example is a lot farther away: NGC 4625, a Magellanic spiral about 30 million light-years away. It has one very obvious spiral arm as well as a bunch of littler ones, and weirdly they all seem to be on one side of the galaxy! Check out this Hubble image of it:

It's beautiful! But yeah, it's a little bit … off. A couple of things threw me when I first saw this image. One is the color; I noticed right away the center of the galaxy looks blue, but in general with spirals the inner regions are populated by older, redder stars. It turns out this is true for NGC 4625 as well! The reason it looks blue in the image is that the colors displayed don't actually represent the colors of the filters used.

When you make a color picture like this you actually take a bunch of black and white images (technically grayscale) through different filters. Then, in post-processing, you layer them with different colors. If you choose to represent the colors as accurately as possible, you choose the red filter image for the red layer, green for the green layer, and blue for the blue layer.

In this case, though, they show the image using the red filter as blue! It's an unusual choice, but I think it was done because there wasn't a lot of good data taken using a blue filter, and it was better to show it this way than leave the blue data out.

They also blended two filter images for red, one that is very red (actually near infrared) and the other that accentuates nitrogen gas, commonly found where stars are being born. See all those pink clumps in the galaxies? Yup. Stellar nurseries.

The other thing that bugged me when I saw this shot is that I wouldn't expect to see such asymmetry in a spiral galaxy unless it had interacted with another galaxy. When two galaxies get near each other, their mutual gravity plays all sorts of havoc with their structure. Sometimes the arms get drawn out like taffy, creating what's called a tidal tail. If the galaxies get really close the changes can be pretty dramatic (especially if they physically collide).

But in that case, where's the other galaxy?

Oh wait. There it is.

That image is from the Galaxy Evolution Explorer, or GALEX, which surveyed the sky in ultraviolet light. NGC 4625 is below, and the galaxy NGC 4618 above. Young stars and hot gas blast out UV light, and those are usually found in the arms of spirals, so those structures are accentuated here. As you can see, NGC 4618 doesn't have really strong arms, but they're there. I found a nice Hubble image of NGC 4618 that shows them a bit better:

The arms are weak but visible. It also has a strong bar, a long rectangular structure across the center, which is common in spiral galaxies; it forms naturally due to gravity of stars spread around the galaxy's disk (details are complex, but I've explained them a bit here and there; the link there will help).

I have to admit, there's much to indicate these galaxies are affecting each other, though. The arms of NGC 4625 appear to be on the opposite side of it from the other galaxy, which hints that they're related, and lots of stars are forming in NGC 4625 as well, which is common after an interaction. But that's about it. Are we sure they're connected in some way?

Yup. Some astronomers observed these galaxies to look at radio waves coming from them; cold hydrogen gas emits that kind of light. They found that this hydrogen gas exists well outside the two galaxies, and there's a huge loop of it circling NGC 4618. That's a sure sign the two have had some dealings with each other before. They have haloes of this gas, and when they passed each other the halo of 4618 got twisted around.

But it's a bit odd that the inner parts of the galaxies appear to be mostly unperturbed; the authors of the radio paper mention this as well. It may have to do with the structures of the galaxies themselves. NGC 4625 has a massive halo of gas around it, and that might act to help stabilize the interior gas and stars through its gravity, preventing them from being messed up in the encounter. On the other hand, NGC 4618 has a weak halo, and that might explain why the spiral arm structure is weak as well; the arms got disturbed without a massive halo to prevent it.

It's amazing how complex these situations are. What happens during a collision depends on so many factors! What the masses (and mass ratios) of the two galaxies are, their detailed structure, how close they get to each other, how quickly they're moving, and on and on. And as NGC 4625 and NGC 4618 show us, the results aren't always an obvious clue to those conditions.

Oh well. I guess we'll just have to keep observing more of these gorgeous cosmic train wrecks so we can keep working on them. I'm OK with that.

… or we could just wait a few billion years and see what happens when the Andromeda galaxy collides with us. But I'm not sure I have that much patience.