Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

What is this galaxy doing without a dark matter halo?

In astronomy we tend to see the biggest, the brightest, the most obvious objects. If something is too faint to see, how do you know it's there? Heck, if there's an entire population of faint objects, they could be hiding in plain sight. We'd overlook them because we simply don't see them.

What are we missing?

Well, there's this: Astronomers have discovered a galaxy that appears to lack a dark matter halo.

Let me assure you: This is very, very weird. Finding a galaxy lacking a dark matter halo is like finding a tree growing from the surface of the ocean. How'd it get there? What's going on? What's it doing?

These are all good questions, and we don't really have answers. Yet. So, let's see what's what here!

The galaxy was found by astronomers using the delightful Dragonfly Telescope Array, which isn't a telescope as you'd probably think of one. It's a collection of a bunch of off-the-shelf (literally) Canon telephoto lenses, each connected to a digital detector and mounted on a framework so they all point in essentially the same direction. The lenses have a special coating on them that greatly reduces scattered light, which makes them extremely adept at seeing large, faint, diffuse objects. In normal telescopes these objects are drowned out by bright stars and other sources of unwanted light. Think of it as glare. Dragonfly reduces glare, so fainter beasties can be seen. It also looks at big patches of sky, to better see lots of things all at once.

One thing Dragonfly excels at is looking for very dim satellite galaxies that orbit bigger ones. Our own Milky Way has dozens of such tiny companions. The main mission for Dragonfly is to take deep images of nearby galaxies to find previously overlooked satellites.

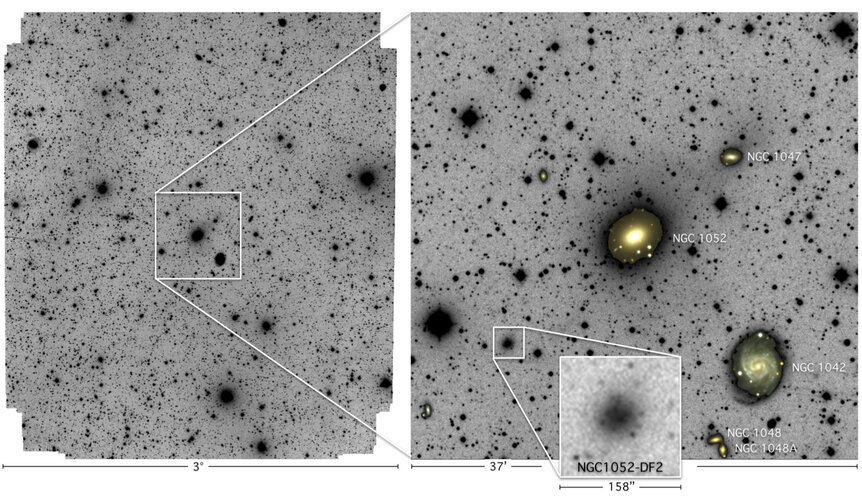

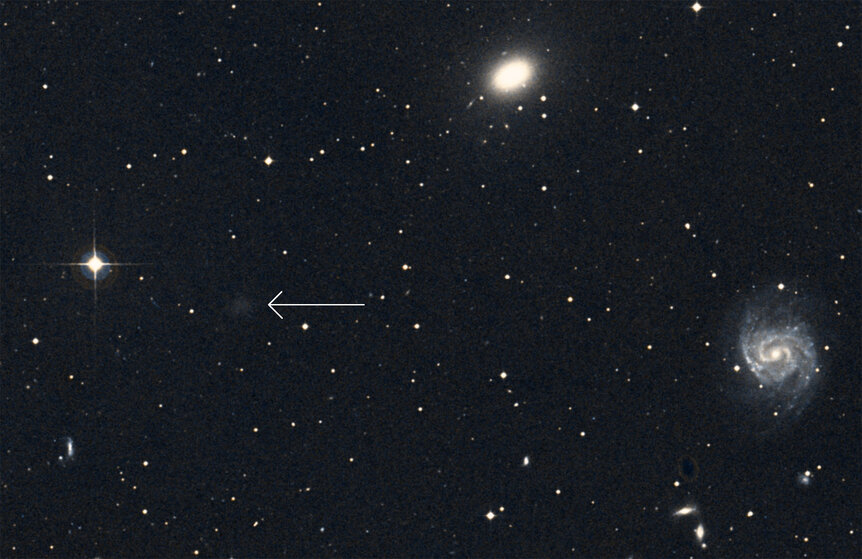

One such galaxy is NGC 1052, an elliptical about 60 million light years away. Using 8 of its lenses, Dragonfly took a look. The astronomers did indeed find a fuzzy looking object nearby, one that had been previously discovered in photographic plates in 2000. Weirdly, though, they saw quite a few bright dots in it, what astronomers call point sources. Intrigued, they used Hubble to get images, and what they saw is very interesting indeed!

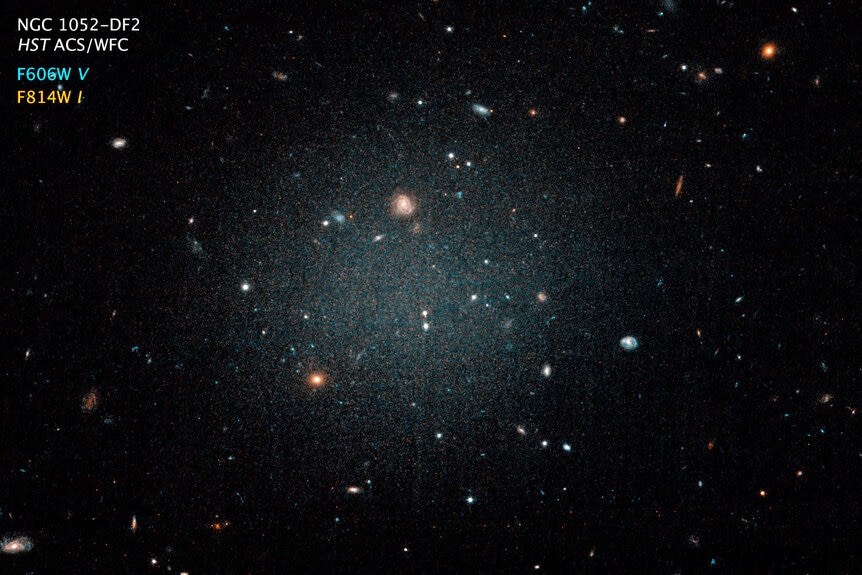

Wow. It's certainly diffuse! But it's weird. To be clear, the galaxy — called NGC 1052-DF2 — is the big bluish vague patch in the center. Almost everything else you see in this image are much more distant background galaxies, even right through NGC 1052-DF2.

To my eye it's just odd. There's no apparent gas in it, no pink fuzzy spots showing nebulae where stars are born. There's no overall structure; just a slightly elliptical shape. And you can see individual stars in it (all the speckles), but cripes, that's it.

However, upon further inspection, you can some of the "stars" are actually brighter than the others, and in the full-res image they are also slightly extended, so they can't be stars. The Dragonfly team identified ten of them, and used the giant Keck observatory in Hawaii to take spectra of these objects. By breaking up their light into extremely fine individual colors, a lot of info can be squeezed out.

For one thing, these objects appear to be globular clusters, self-contained collections of many thousands of stars held together by their own gravity. Even then, these are weird too, because they're brighter than most other globulars seen in other galaxies, including our own.

But they have another secret in their spectra. Their velocities can be measured. This is critical, because how fast they move depends on how much gravity they feel from the galaxy they orbit, and that tells you how much mass the galaxy has. Looking at the distribution of their speeds as they circle NGC 1052-DF2, the astronomers calculate there's no more than about 320 million times the mass of our Sun in that galaxy, and most likely quite a bit less, closer to 200 million. And that's very very interesting.

Why? Because by looking at how much light they see from the galaxy, they can also infer the total mass of the stars therein, and what they get is… about 200 million times the mass of the Sun (they actually used a couple of different methods to look into this, and both agreed on that number).

What that means is that all the mass of the galaxy is locked up in stars.

And that's where we have a problem. Every galaxy we look at is surrounded by a halo of dark matter, a mysterious form of matter we don't understand well but that we know exists. It outmasses regular, normal matter by about 6 to 1 in the Universe, and we think it's critical for galaxies to form in the first place. The actual amount in a galaxy's halo depends on lots of things, including the number of stars in an individual galaxy, but for small dwarf galaxies we expect the dark matter to outweigh normal matter by a factor of several hundred.

And NGC 1052-DF2 appears to have none. Or at best, about as much dark matter as normal matter. And that just doesn't make sense.

Where did the dark matter go? It's not clear. A better question might be, did this galaxy have a dark matter halo in the first place? Perhaps it formed from gas stripped out of NGC 1052, the nearby elliptical galaxy. That can happen when two biggish galaxies collide… or the gas could have been blown out by the gigantic supermassive black hole we know sits in the center of NGC 1052. Or maybe it was gas falling into NGC 1052 that fragmented and formed stars before it could complete its descent into the bigger galaxy.

The only clues we have right now are that this galaxy has four oddities: It's bigger than most dwarfs, it's more diffuse than most dwarfs, it has those weirdly bright globular clusters, and it has no dark matter. What is this telling us?

It's hard to say. The fun thing about discovering a one-of-a-kind object is that you have way more questions than answers. There are two ways to fix this: Keep looking at it to glean more clues from it, and to look for more objects like it.

Dragonfly is doing the latter, looking for more such critters lurking around nearby galaxies. I know they'll find plenty of dwarf companions, but it's anyone's guess if they'll find something that looks like NGC 1052-DF2. Maybe it is unique.

But I seriously doubt it. Whenever we open a new kind of eye to the sky, we find an object we hadn't expected (or an old object behaving in ways we hadn't expected). In fact, Dragonfly images were used by this same team of astronomers to discover the existence of a new kind of galaxy, called Ultra Diffuse Galaxies! So this little array is making big advances in astronomy by looking in the same places other telescopes do, but doing it in a different way.

Let me leave you with this. There's an old joke nearly every astronomer knows.

A cop sees a kid under a streetlight at dusk. The kid is on his hands and knees, looking for something. The cop asks the kid what he's doing. "I dropped a quarter and I'm looking for it."

"Where did you drop it?" the cop asks.

The kid points to a dark spot a ways away. "Over there."

"Why are you looking here then?"

The kid shrugs. "The light is better here."

We need to look where the light's better, sure. But we also need to look in the dark corners, too, the murky places where things hide. Because who knows what we're missing if we don't.