Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

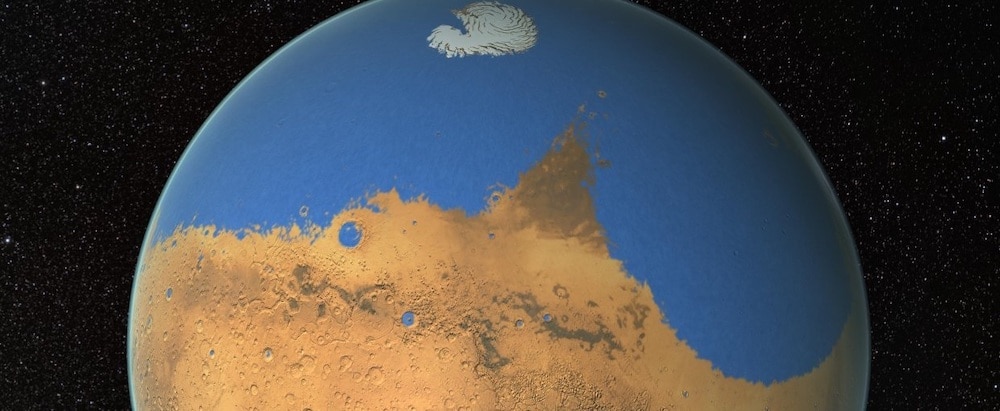

Dive in! Ancient Mars had enough water for a global ocean 300 meters deep

Take a deep breath!

During the ordinary course of day to day life, we tend to think of planets as being unmoving and unchanging. There are few things more dependable than the ground beneath our feet, but that’s only because our experiences are limited by time. On long enough timescales — brief even, in geological time — we see that the worlds are constantly shifting and evolving, through forces both internal and external. To a planet, these events are no big thing, but we call them natural disasters and make movies about them. Like Oceans Rising, now streaming on Peacock!

In it, scientist Josh Chamberlain attempts to warn the world of a coming flood, but he is ignored and forced to build a boat to survive the coming deluge like a modern day Noah. While the movie offers a hand-waving explanation involving a reversed electrical field and melting polar ice caps, the notion of changing planetary water levels isn’t that farfetched. At least if you take the wide view of time.

Recently, scientists from the University of Paris, University of Copenhagen, University of Bern, and ETH Zurich revealed that Mars — famous for its dusty red surface and dry desert landscapes — may once have had more water than it rightly knew what to do with. That’s according to a new study published in the journal Science Advances.

To get our hands around what might have happened, we first have to dial back the clock to just before the solar system existed at all. It started with a massive cloud of gas with tiny solid dust particles mixed in. Slowly, under the persistent pull of gravity, that gas and dust began to come together in a process known as accretion. At first there were only small objects, balls of dirt, rock or ice. Later, those small objects got larger, gathering more material like a snowball racing down an icy mountain. The largest of those conglomerations became the Sun. The runners up: the planets. But after the champion was crowned and the ribbons handed out, the solar system was left with a horrifying number of leftover ingredients, small objects that didn’t get to one of the planetary collection sites on time and were whipping around the solar system like they were running late. Because they were.

This period of late arrivals lasted about 700 million years, between 4.5 and 3.8 billion years ago and is known as the Late Heavy Bombardment. During this time, the planets were smacked over and over again, like the cosmic version of E. Honda’s Hundred Hand Slap.

One hypothesis about this period is that gas giants funneled small impactors — small being relative in this case, some of them were real bangers — into the inner solar system where they made cataclysmic contact with the smaller rocky planets. Jupiter has since made up for this attack and now appears to protect us from those same impactors, for the most part.

In those early days, however, it was a rough time to be a burgeoning rocky planet. According to the new paper, Mars endured a period of 100 million years of its early development during which the celestial welcoming committee hit it with shotgun blast after shotgun blast of comets and asteroids, many of which were carrying buckets full of water. In fact, Mars might have been the emperor of oceans when the solar system first began.

RELATED: If ancient Mars had oceans, where exactly are they?

Because Mars doesn’t have active plate tectonics that recycle its surface features, the Martian crust preserves an ancient record of the planet’s history in the sediment. Researchers analyzed the variability of chromium isotopes in 31 Martian meteorites to gain clues about the planet’s past. By studying those meteorites, which are effectively preserved pieces of an unchanged ancient planet, scientists can gain information about the planet’s original composition, development, and chemistry at the surface.

In short, by looking at the composition of those meteorites, scientists can infer how heavily Mars was impacted early on, and thereby estimate how much water might have been delivered to the red planet by those impactors. When all the numbers were crunched, the team landed on a truly staggering number. The data suggests that Mars once had enough water to be covered in a planet-wide ocean at least 300 meters deep. Some estimates put it closer to a full kilometer.

Notably, those selfsame impactors could have delivered organic molecules like amino acids — important note: those molecules wouldn’t have been alive but might have been some of the needed ingredients for life to later emerge — potentially jumpstarting any potential life that might have arisen there. Meanwhile, the Earth was recovering from a head-to-head dust up with a protoplanet called Theia, which would ultimately form the Moon. This is what it’s like when worlds collide, as the great philosopher Powerman 5000 would say.

The early solar system would have been a very different place, with a thriving and lush Mars and a shattered and molten Earth. But in the due course of time, the worlds turn, and so do the tables.