Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The day the Sun erupted

The Sun is a fickle beast. Sometimes it's calm, just shining and spinning and being a star, and other times, without warning, it can erupt with violence to crush the imagination.

It all depends on magnetism. Deep inside the Sun, it's very, very hot, and hydrogen is ionized: The atoms have their electrons stripped off. Not only that, but that heat causes the gas to rise, just as hot air rises and cool air sinks. We call this motion convection.

The thing is, when you move a charged particle you generate a magnetic field, so every rising parcel of ionized gas — plasma — inside the Sun contains its own magnetic field, writhing and twisting. It's like a bag filled with thousand amorphous magnets moving inside the Sun, rising to the surface.

The north and south poles of the magnetic field are connected by invisible lines of force called magnetic field lines, and these store vast amounts of energy. I mean, vast. When the bubbles of plasma reach the Sun's surface all sorts of things can happen. You can get huge loops of plasma flowing along them, or even larger arcs that are like natural bridges across tens or hundreds of thousands of kilometers of solar real estate. When we see these arcs against the Sun's face we call them filaments, and when we see them off the edge of the Sun's disk against the background of space they're called prominences (it's the same structure but has different names for historical reasons).

Those field lines interact with each other and twist around, causing huge amounts of stress. Sometimes they snap, and when they do, all that vast energy is released.

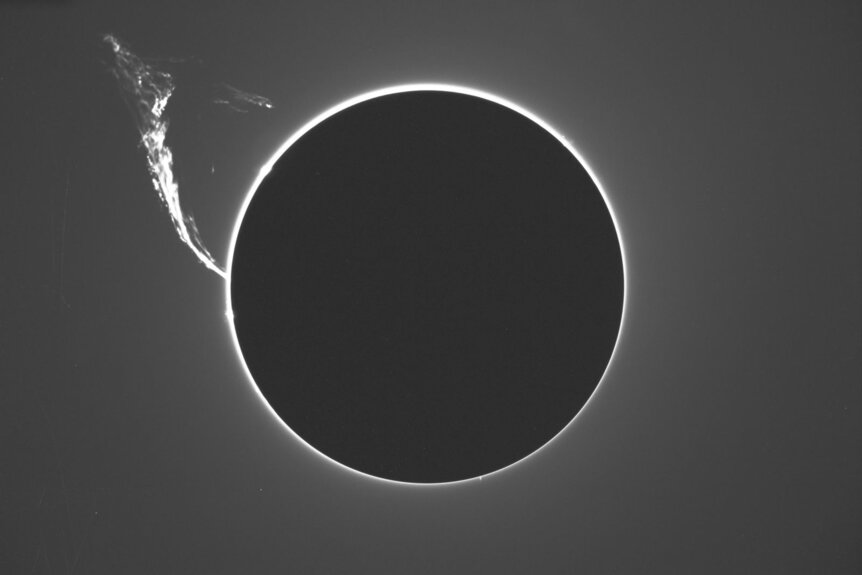

On July 31, 1992, astronomers at the Norikura Solar Observatory in Japan watched in awe as a colossal prominence formed on the Sun, then erupted off the surface. Here is an image of this event:

They used a coronograph, a device that blocks the bright disk of the Sun and allows fainter structures around it to be seen. This is a one-second exposure using a 10-centimeter telescope (that's really small!) and a filter that specifically lets through the light from warm hydrogen.

The scale of this is nearly unimagineable. When this image was taken the tip of the eruptive prominence was nearly 600,000 kilometers above the Sun's surface, and the length of the arc was probably closer to 800,000 km. On this scale, the Earth would be a dot, difficult to even see.

The energy of the event is also mind-crushingly colossal. Millions of tons of gas exploded outward at a velocity of 100 kilometers per second, and the magnetic energy heated parts of it to several million degrees Celsius.

Eruptive prominences are uncommon, though not exactly rare. One this size, though, doesn't blast away every day on the Sun. The last really big one was in 2012, when an arc about 300,000 km across blew out into space. That was seen by the wonderful Solar Dynamics Observatory, which took an image of it that's one of my all-time favorite solar views:

Yeah. That's a composite of two ultraviolet images, and the detail is just exceptional. We've come a long way in two decades!

The Sun's magnetic activity waxes and wanes on an 11-year cycle, and we're approaching a minimum now; the Sun has been pretty quiet for some time (which is why I haven't written much about it for a while). But in a few years it'll ramp up once again, and we'll start to see more prominences, more flares, and more coronal mass ejections. These can interact with the Earth's magnetic field, creating all kinds of havoc (brownouts, blackouts, and can even damage satellites in orbit if the event is powerful enough).

Stay tuned. If the Sun decides to throw another tantrum, astronomers around the world — and their eyes above it — will be ready.