Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

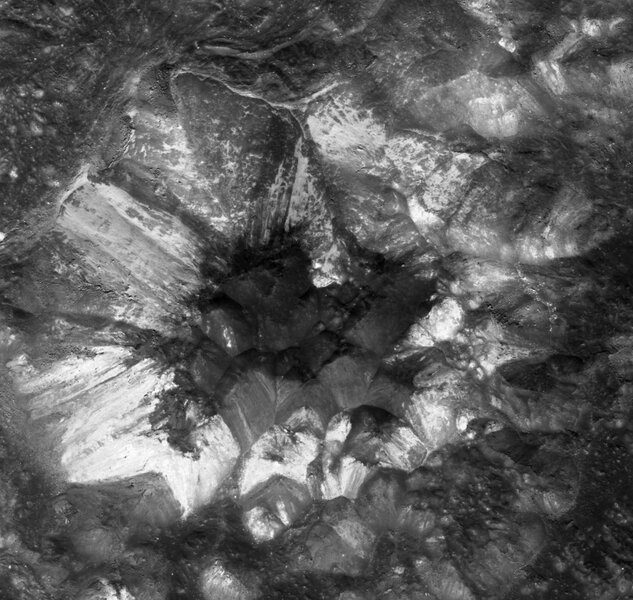

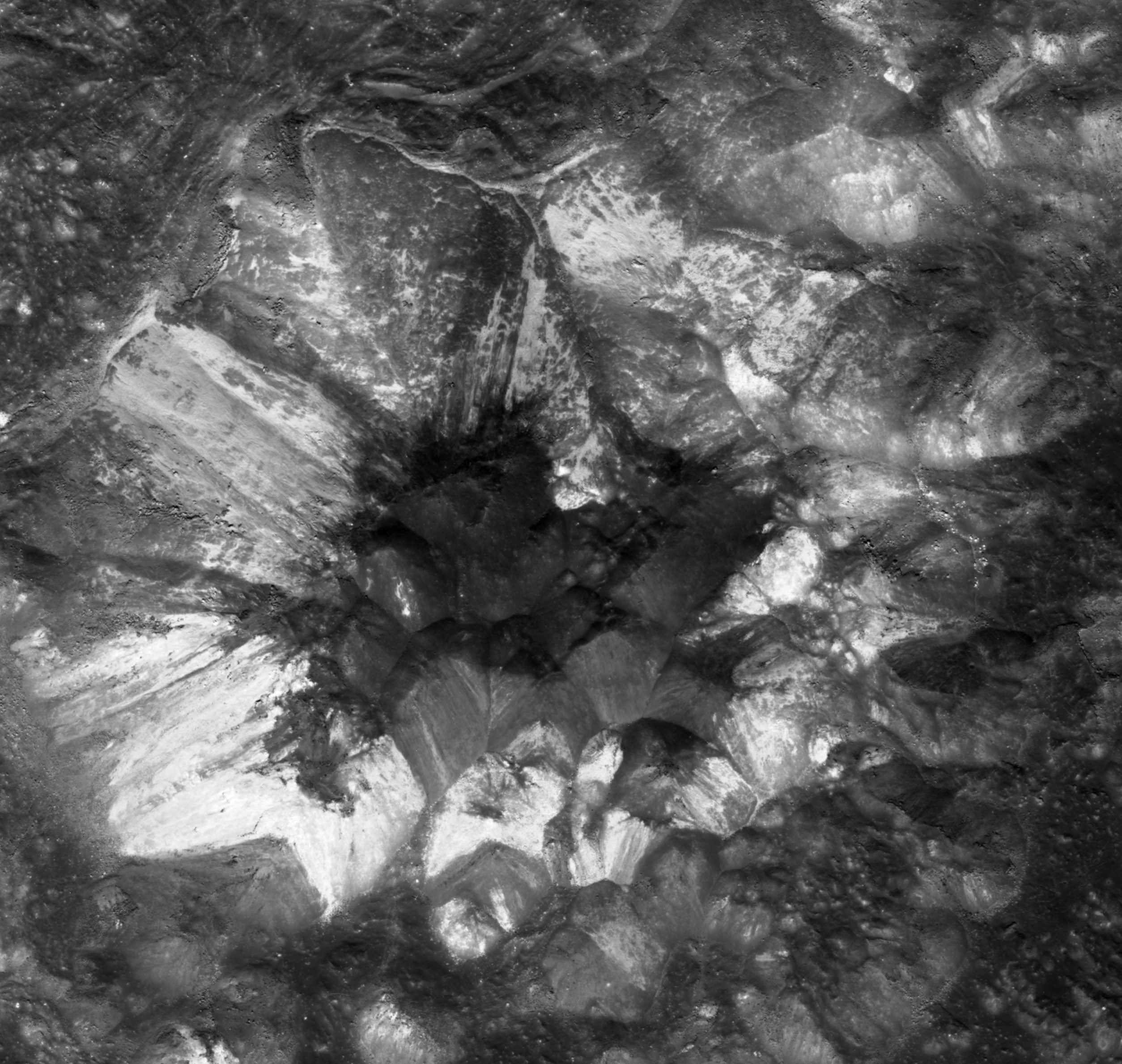

The jumbled mess in the center of Jackson Crater

Jackson is a crater on the far side of the Moon, a little north of the equator. It's decent-sized, at a little over 70 kilometers across.

By "decent-sized" I mean that it's bigger than most craters on the Moon. But in human terms a crater 70 kilometers means the Moon suffered a helluva wallop when it formed. The asteroid or comet that hit there must have been very roughly the same size as the one that wiped out the dinosaurs here on Earth. At least several kilometers across!

An impact like that makes a big mess of the surface. The vast pressure and energy release from the impact melts rock on the surface down to a depth of many kilometers, and at the same time that pressure pushes that material away from the impact point. That's what carves the crater bowl.

After the initial explosion, rock that got pushed away will flow back toward the center in a process called rebound. That inward rush meets in the middle and splashes upward, forming a central peak, a jagged mountain in the center. Not long after that, rock that has molten on the crater floor will flow in, filling in depressions and creating "melt pools." As the rock cools huge cracks can appear in the surface.

All of this can be seen in the middle of Jackson… especially when you have the keen eye of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has taken multiple images of Jackson as it's been circling the Moon since 2009. But one of these observations stands out, just like the central peak it shows. Check this out:

That image, showing a region about 10 kilometers across, is certainly bizarre, isn't it? Partly this is due to the illumination; the Sun was shining nearly straight down when this image was taken, so relief in the terrain is downplayed (we generally judge elevation using shadowing, but with the high Sun that's nearly impossible). Instead, materials with different reflectivity (that is, different brightness) are exaggerated, dialing the contrast way up.

Complicating this further is the fact that the central peak is made of different materials dredged up from under the lunar surface, some of which is very dark and some of which is very bright. It helps to have a wider view with the Sun at a lower angle, so you can see elevation differences.

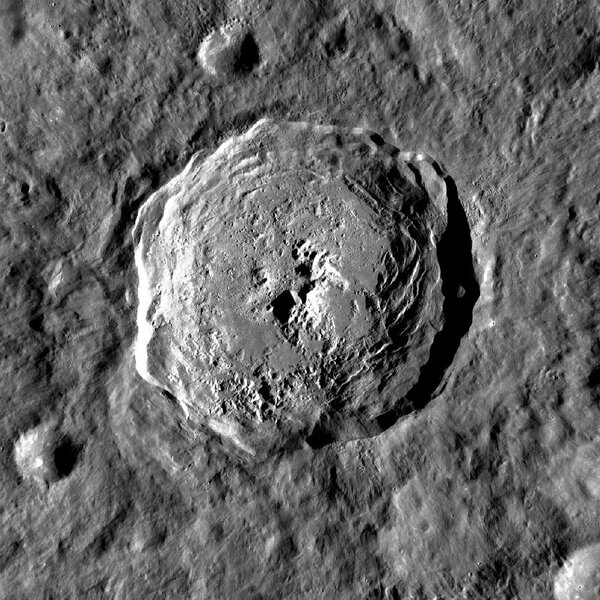

This image was taken using the LRO wide-angle camera, and shows the whole crater. The central peak is actually a complex set of jagged hills, with one big monolith to the lower left, and a crescent of hills running counterclockwise from it. That monolith is seen in the first image above as the darkest hill in the center. As you can tell if you spend a moment comparing the two, the white streaks in the detailed image which look like steep hills are actually much more gentle, leading outward to much smoother regions; those are the melt ponds. Even then this is hard to see, so here's a medium-wide shot (roughly 10x15 km) that puts things into perspective as well:

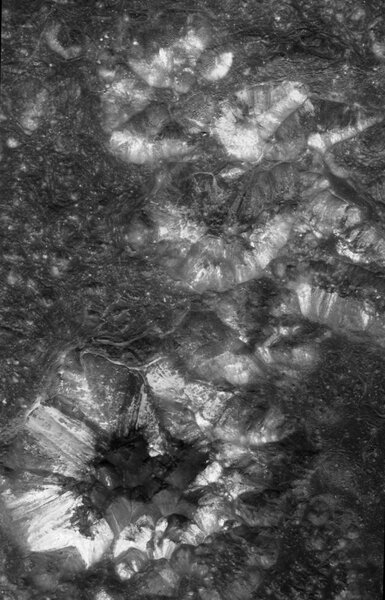

Now you can see the central peak and the semicircular hills better. Ripples of melt billow up to the monolith on the top side, as well as at the top of the other hills. You can see some cracking in it too, created as the molten rock cooled and contracted. Numerous huge boulders dot the whole area as well.

What a mess. But what a dream for geologists! The beauty of craters (besides their actual, literal beauty) is that they take stuff from deep below the surface and splay it out for all to see. That does make it somewhat harder to interpret how it all got where it is, but that inconvenience is alleviated somewhat by being able to see this stuff at all, given that moments before the impact it was buried a few kilometers under billions of tons of rock.

I can easily imagine future geologists hiking this area, taking samples and learning about what lies beneath it. And when I envision this in my mind's eye, I always wonder: Are those lunar scientists alive today? Is some preschool student playing in a pile of sand right now, dropping rocks and marveling at the results, wondering how those bowl-shaped depressions formed? And are they just a single view through a telescope's eyepiece away from being inspired to wonder what that same thing would do on our Moon?

[N.B. As usual, I got the first image and the inspiration to write this article from the LRO Camera blog, which features jaw-dropping images of our nearest celestial neighbor. Seriously, bookmark them, or RSS feed them, or do whatever you do to remind yourself to go there. It's wonderful.]