Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Tiangong-1 burned up over the Pacific Ocean

The Chinese space station Tiangong-1 burned up in Earth's atmosphere over the central south Pacific Ocean last night, April 2, 2018, at approximately 00:16 UTC (8:16 p.m. Eastern U.S. time).

This is a huge region of ocean, so it's extremely unlikely we'll see any photographs of the re-entry (unless some were taken by other satellites in orbit or ships and planes in the area, but it may be a while before those surface, if at all). Some of the space station would have survived re-entry and hit the water, but out there it would have just sunk beneath the waves.

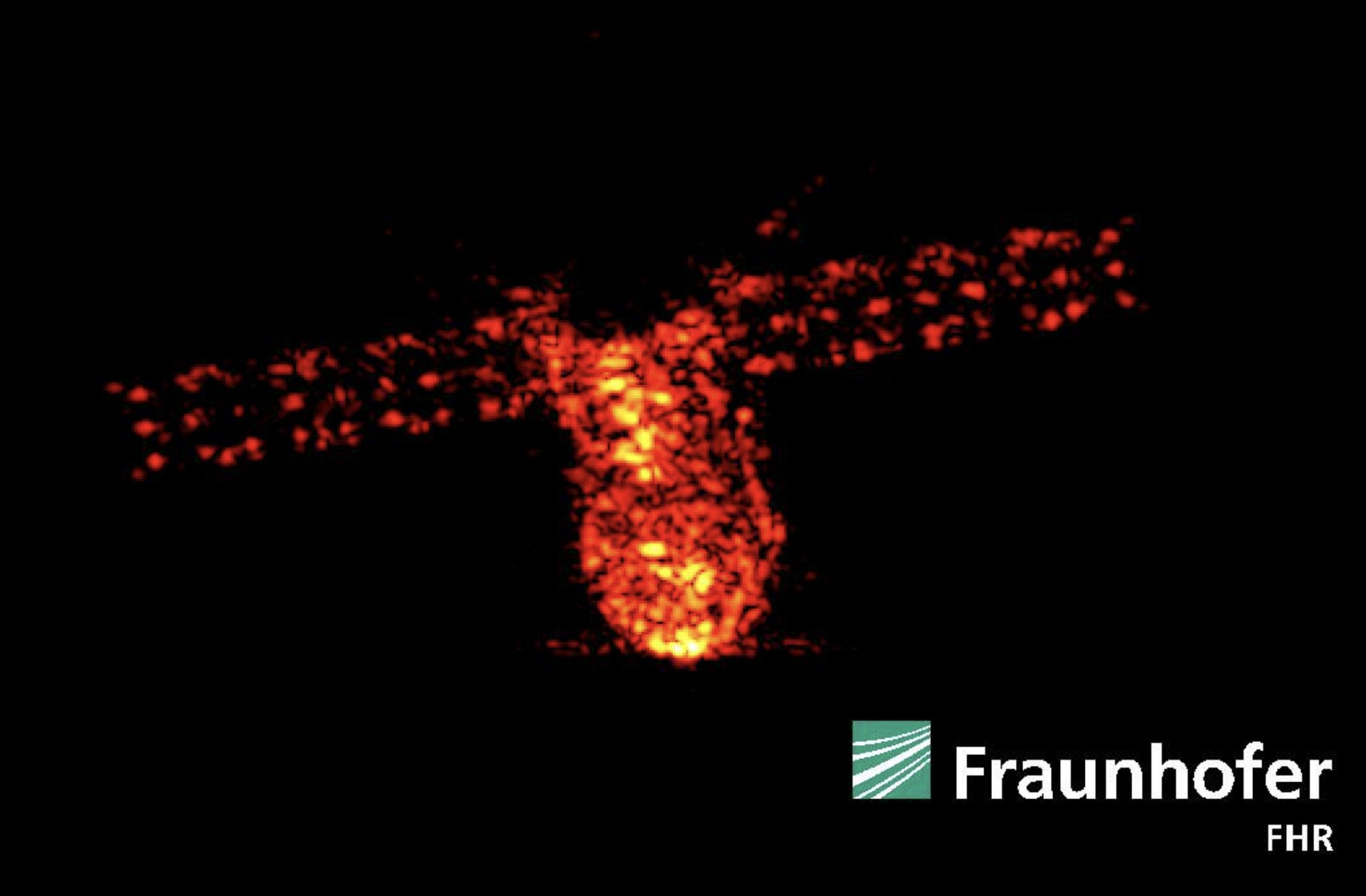

The space station was launched into orbit by China in 2011, and visited three times by Chinese spacecraft (once by an uncrewed and twice by a crewed mission). It was about 10 meters long — slightly shorter than a school bus — and had a mass of over 9 tons.

It had the capability of de-orbiting itself using onboard engines, but the Chinese space agency lost contact with it in 2016. Because of that they couldn't command it to fire its engines at the right time to drop it on an uninhabited spot. In general that's the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, and as it happens that's indeed where it ended up. That's not entirely coincidence; the Pacific is so big that just by random chance it was likely to fall there.

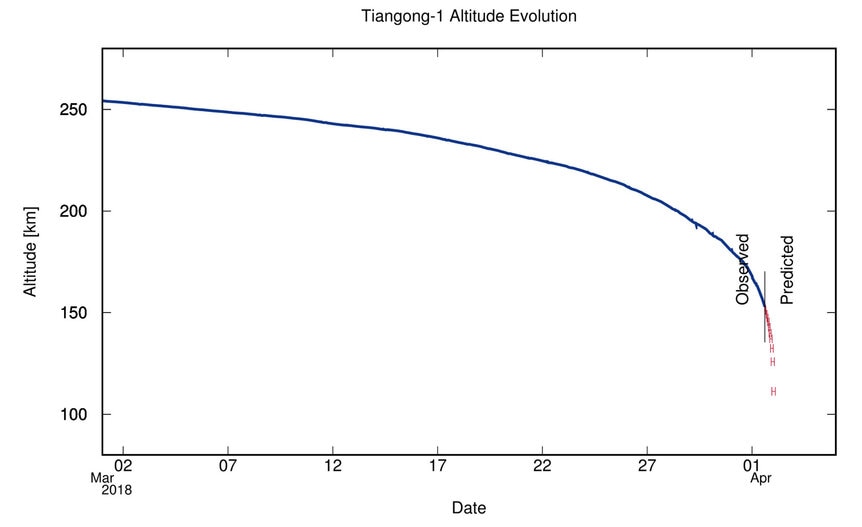

Predictions made months ago put the re-entry time around now, but it's not possible to know exactly when or where it would come down. Orbital speed is 8 kilometers per second, so if you're off by an hour it could be thousands of kilometers away.

I saw some confusion over this whole thing on social media. Briefly, when an object is in orbit it's not flying like an airplane; it's only being controlled by gravity. In general if you put something in orbit it'll stay there forever, falling due to gravity around the planet.

However, in low Earth orbit, up to a few hundred kilometers above the surface, there is a little bit of air. It's not much, because the atmosphere thins with height, but even at 400 km or so there's some. Every time an orbiting spacecraft hits an air molecule, that collision robs the craft of a little bit of energy. Over time that lowers the orbit of the spacecraft. Usually, spacecraft can be reboosted to a higher orbit; the International Space Station (ISS) has done this many times. During servicing missions, the Shuttle was used to boost the Hubble Space Telescope higher in orbit as well.

Left unchecked, though, this lowering orbital height is a vicious circle. As the spacecraft drops, the air gets thicker, and the drag increases, dropping it more and faster. This is an incredibly small effect at first, and it can take years for an orbit to drop, but in the case of Tiangong-1 the outcome was inevitable. Over the past few days it dropped ever faster, until, finally, the air was thick enough to destroy the spacecraft.

This happens two ways. One is that the simple pressure tore parts off the space station. Also, as the spacecraft rammed through the air, it compressed the gas in front of it. A compressed gas heats up, and when you compress it by plowing through it at 8 km/sec, the heat is enough to melt metal and cause things to glow. Together, these two forces vaporized and ripped apart Tiangong-1. Most of it burned up, and some of it no doubt was dense enough to survive re-entry and hit the water.

I'll note the Chinese have a second station, Tiangong-2, still in orbit. It was last visited by a spacecraft in 2017. They also have plans for a much larger, modular station, more like ISS, to be started in 2019.

It's rare for something this big to re-enter, but it does happen. Let's hope that, after what just occurred, the Chinese space agency takes a serious look at their plans and engineering, and minimizes any risk for an event like this happening again.

Special thanks to my friend Jonathan McDowell, who kept Twitter up to date on these events. Follow him for great space news coverage.