Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Velvet Buzzsaw makes horror from art, greed and annoying critics

WARNING: This article contains spoilers for Netflix'sVelvet Buzzsaw. Continue at your own peril.

Velvet Buzzsaw is the kind of film that could probably only be made by Netflix nowadays. It’s the sort of high-concept story that gleefully rejects notions of mainstream appeal that studios and producers are hesitant to put money into in the current market. Even with an award-winning writer-director at the helm and a murderer’s row of talent in its ensemble, Velvet Buzzsaw is a tough sell. After all, how do you package to the masses a scathing satire of the Los Angeles modern art market that suddenly turns into Final Destination in its second act?

The film follows a circle of friends, acquaintances, clients, and enemies who populate the high-stakes world of modern art. The profits are high, the artistic merit questionable, and the moral investment questionable. There’s the delightfully named art critic Morf Vandewalt (Jake Gyllenhaal), who seems more obsessed with setting trends than enjoying the art he tears to shreds in his scarily influential column; artistic agent Rhodora Haze (Rene Russo), a former punk rocker who chases the money over all else; gallery worker Gretchen (Toni Collette), who is following suit and selling out; Rhodora's assistant Josephina (Zawe Ashton), desperate to make her way up the ranks of her profession; and Jon Dondon (Tom Sturridge), a competing gallery owner trying to snatch up the most profitable clients.

The artists themselves are barely players in this world, from Piers (John Malkovich), a Jeff Koons-style pop art legend who has been struck hard with artistic block since sobering up, to Damrish (Daveed Diggs), a street artist torn between big profit and true integrity. Their worlds collide when Josephina discovers that one of her neighbors has died and left behind a cache of paintings. Soon, the late and enigmatic Vetril Dease is the hottest name in outsider art and people are willing to pay millions for his work. It's just a shame his spirit has other ideas.

The first half of Velvet Buzzsaw is surprisingly horror-free. There are a few moments of creepy eyes on portraits and the prerequisite jump scares, but if you went into this film not knowing its concept, you’d end up thinking this was simply a black comedy about the self-serving narcissists of the art world. In many ways, it might have been a better film if it had committed to that concept. There’s a really fascinating narrative at the heart of this story, wherein someone decides to take a dead man’s work and make it the biggest thing on the art market but must deal with the fallout when his dark and problematic past is exposed. Velvet Buzzsaw mostly avoids such potential in favor of easier gags. Satire of the art world is nothing new, partly because it’s a ridiculous place that’s ripe for mockery, but it’s easy to play it too broadly or go for the cheap jokes, and Velvet Buzzsaw is no exception. In one scene, Jon Dondon harkens a bag of trash in Piers’ studio as his greatest work yet, not realizing that it’s just a bag of trash.Where the film succeeds is in how it makes horror from art and vice versa. One of the real struggles of storytelling is when you have to convince your audience that the genius you are spending so much time building up in your narrative is worthy of that label. Think of how many times you’ve read a book about an amazing poet or seen a film about a legendary director and then their fictional work never lives up to that declaration. With the work of Vetril Dease, Gilroy has something of a get-out-of-jail-free card in that the supernatural is involved. Hey, maybe people are hypnotized by his art because of the spirits? The Dease paintings themselves are certainly striking — full of bold strokes, stretched faces of terror, and sharp colors. Dease’s ramshackle studio is covered in cut-outs of legendary artists like Rembrandt and Caravaggio, emphasizing his classic influences, but his background in the film aligns more with outsider figures like Henry Darger.

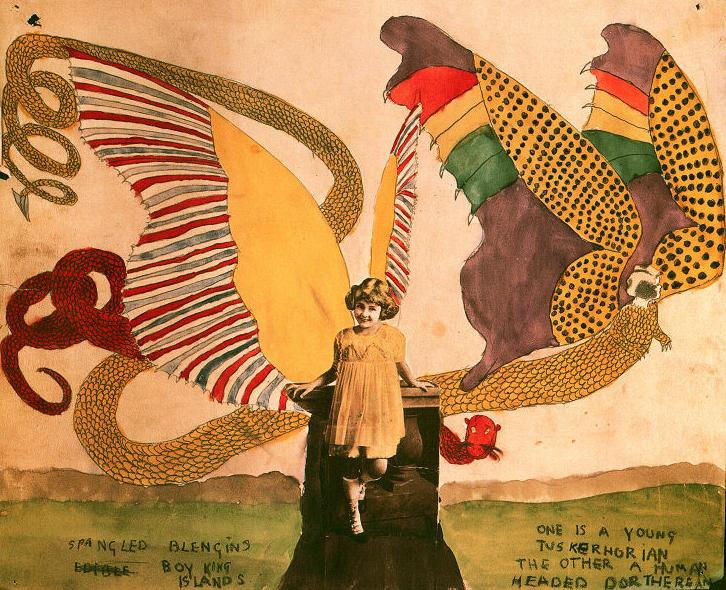

Like Dease, Darger was posthumously discovered and had potentially thousands of pieces of art in his home, where he lived reclusively following a difficult childhood. Darger wrote a 15,145-page fantasy manuscript called The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, for which he created hundreds of accompanying drawings and paintings as illustrations. Nowadays, Darger's work can be found in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the American Folk Art Museum in New York, among other locations around the world. He's been credited as an influence on everyone from Jake and Dinos Chapman to Scott McCloud. He's also sparked endless conversations about the ethics of art and the appropriation of those who made it. Darger never seemed to call himself an artist or deem what he created to be art. He never sought to exhibit it or profit from it, but plenty of others have done so since his passing. If art is now an inevitable mill of profit and celebrity, what happens to the work itself when it's displayed in such a way that the creator never intended?Gilroy’s solution to this conundrum in Velvet Buzzsaw is pretty simple: Dease wanted his work destroyed after his death, so anyone profiting from it will die horribly. Once the second act of the film kicks off and embraces its pop art slasher status, it’s a hell of a lot of fun. One character dies after putting their arm into a Jeff Koons-style metallic sphere and having it chewed off. Another meets an untimely end when a robotic art installment breaks their neck. The most visually striking death comes through paint absorption. When the film goes full kitsch, you feel the energy it’s going for, but it so easily could have gone further. Art has a long and violent history, and some of the most iconic pieces of our times depict horrors beyond our imagination. Think of Saturn Devouring His Son by Goya or Picasso's Guernica or the Chapman brothers’ Hell. There are so many ways the film could have blended such horror with artistic weirdness. If you love modern art like me, you’re practically drowning in possibilities (death by Damien Hirst’s shark!).

Dease’s posthumous anger is directed not at the people who appreciate his art but those who try to make money from it, be they the gallery owners, the critics trying to cash in with a book deal, or the grunt worker who covets what he cannot afford. There’s a stark divide between the work of art and the commerce of it, and it’s clear where both Dease and Gilroy’s intentions lie. So, of course, we get another stock critic character who is a preening narcissist with no artistic skills of their own and a crushing need to destroy everyone else’s hard work. Granted, most of us don’t look like Jake Gyllenhaal (and the film goes to great lengths to show off his pilates body — not that we’re complaining). It’s a rarity to see a critic of any kind depicted in pop culture who isn’t a bitter shrew. At least within the garish context of Velvet Buzzsaw, it makes some sense, but given how often everyone is willing to call Gyllenhaal’s character a sell-out and bully, and given how overtly comedic his death is compared to everyone else’s, the subtext of his arc is nothing new.

Velvet Buzzsaw doesn’t answer the big question it sets up of whether art’s intrinsic value can remain when it becomes a product to exchange for cash. It’s having way too much fun slaughtering people for that, and I can’t blame them for doing so. It’s still a let-down to see such lofty intentions give way to an execution that pulls a few too many punches. It’s a worthwhile watch, if only because you’re highly unlikely to see a horror movie like this again anytime soon. The modern art of our world remains far weirder than any painting that could kill.