Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

An 1811 Earthquake Might Still Be Releasing Aftershocks More Than Two Centuries Later

Apparently, there's no expiration date on aftershocks.

It was an otherwise ordinary day in Los Angeles when a sinkhole opened up, swallowing people and property in NBC’s La Brea, streaming now on Peacock. When the survivors awoke, shaken but alive, they found themselves in an ancient lost world with no way home. Sinkholes that cross space-time aren’t a typical geological activity, but at least Californians expect to mistrust the ground beneath them.

On the other side of the country and in the real world, residents of the New Madrid seismic region might still be suffering aftershocks from a massive quake which struck two centuries ago. That’s according to a recent study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth.

Some Aftershocks Could Last for Centuries

Aftershocks are a well-known phenomenon in the wake of large earthquakes, but the boundaries of their activities aren’t wholly understood. They usually happen in the same fault zone as the main shock and are a normal part of the resettling process. Once there’s a big shakeup, the ground beneath us has to readjust into a new stable position. Sometimes smaller misalignments stick around for a while, settling hours or days later and bringing aftershocks with them.

RELATED: Seattle was Rocked by a Devastating Double Earthquake 1,100 Years Ago

The general wisdom is that aftershocks occur relatively soon after a main shock and stop happening relatively quickly. You wouldn’t expect, for instance, to have a quake one day and an aftershock a year later. But maybe you should. New analysis of the New Madrid region suggests that even some modern quakes are actually aftershocks more than 200 years in the making.

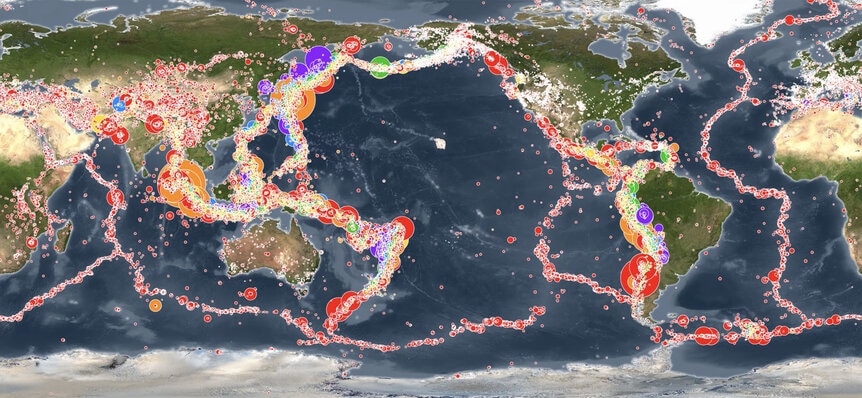

The New Madrid seismic zone is one of the most active geologic regions east of the Rocky Mountains. During the winter of 1811 - 1812, there were a series of earthquakes which lasted months. Among them were three large quakes estimated to have peaked between 7 and 8 on the Richter scale.

On timescales that long it’s difficult to separate aftershocks from background seismic activity. To sort one shakeup for another, researchers used the Nearest Neighbor (NN) method, calculating the distances between quakes in both space and time to determine if they are related. The idea is to look at any two events and determine mathematically if they are more likely to be related or unrelated. Their findings suggest that a trio of quakes in the winter of 1811 - 1812 were so powerful that between 10.7% and 65% of all modern quakes in the region greater than magnitude 2.5 can be explained as aftershocks.

RELATED: Predicting Earthquakes Anywhere on Earth with GPS

Researchers used the same method to analyze the 1886 quake in Charleston, South Carolina. They found that 72% of modern quakes are likely aftershocks from that long ago earthquake. Of course, we didn’t have seismometers set up in those areas a couple of centuries ago, so the strength and impact of those quakes have to be inferred. Modern quakes in the New Madrid region can only be explained as aftershocks if the 1811 - 1812 quakes were particularly powerful. It’s also worth noting that a separate study from 2014 made its own analysis and found no evidence of long-lived aftershocks, highlighting the difficulty of identifying aftershocks from background activity.

Part of the trouble is that there’s no clear dividing line between a foreshock, a main shock, and an aftershock. Generally speaking, a quake is considered an aftershock if it follows a main shock and remains above the background rate of seismic activity. Once activity falls to the normal rate, any new quakes are considered a separate incident. In areas like California, where seismic activity is more frequent, aftershock activity falls below the background rate pretty quickly. Closer to the Mississippi River that’s not the case. It becomes more difficult to determine if current quakes are related to old ones or independent geologic actors. Although, when an earthquake hits, most of us are less concerned with why the ground is shaking and more concerned with the fact that it is shaking at all.

Things could be worse, you could have fallen through a sinkhole and through time in La Brea, streaming now on Peacock.