Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

An asteroid impacted the Moon during the lunar eclipse!

Did you see the total lunar eclipse last Sunday night/Monday morning? It was quite lovely, as all such eclipses are.

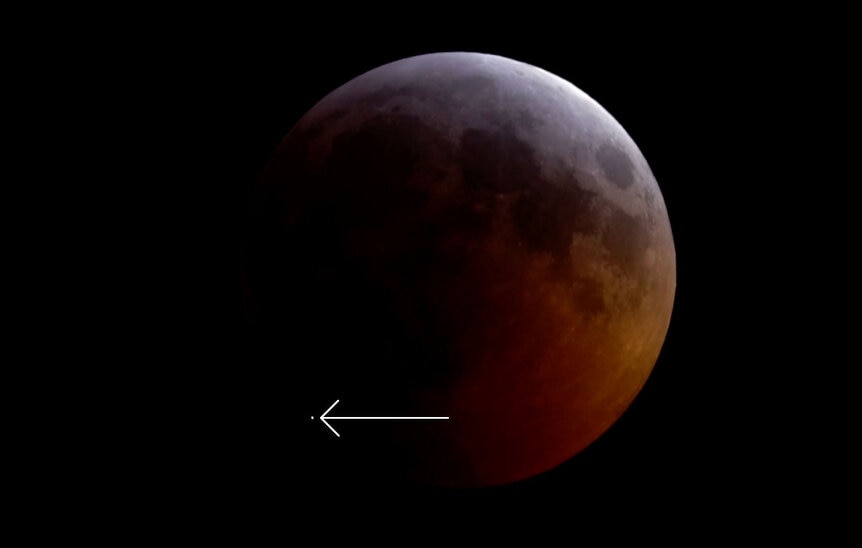

But if you did watch, and happened to be looking at the Moon at the right time — around 04:41:43 UTC (11:41:43 p.m. US eastern time), give or take — you may have seen a pretty cool bonus: A small asteroid impacted the Moon, giving off a bright flash!

The impact occurred just moments after totality began — the moment when the last bit of Moon slipped into the deeper part of Earth's shadow. A lot of people claim to have noticed it on their own, not sure of what they saw at the time, but as it happens there were quite a few live streams through telescopes at the time, and many of them caught the extremely brief flash.

The Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles was doing a live feed using their lovely 30-cm Zeiss refractor, and the flash of light can be seen on the lower left edge of the Moon, very near the limb (I've set the video to start a few seconds before the impact, which occurs at 3:43:11 in the video; it may help to slow the playback speed to 1/2):

Did you catch it? It's fast! Here's a screen capture:

Here's another view, this one from the TimeandDate.com's live feed. Again the video is set to start a few seconds before the flash (which happens at 1:20:46), which in this view is more to the upper left of the Moon:

Here's a screen capture from that feed:

It was also seen by the MIDAS survey (Moon Impacts Detection and Analysis System), designed specifically to capture impact flashes:

Incidentally, NASA has been monitoring lunar impacts for quite some time. We've seen lots before, but any new one seen is still important.

This is more than just a cool curiosity: If the impact site can be found with high enough accuracy, it's possible the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter can get images of it! The brightness of the impact flash seen depends mostly on the mass of the impactor and the velocity at which it was traveling (see below), so if LRO can spot the crater and measure its size, that too can be tied with other physical properties of whatever hit the Moon.

These and other videos, plus images taken by people back on Earth, can help nail down the impact site location. Unfortunately, what we've seen so far is only good to a few kilometers accuracy on the impact position, so I'm making a public plea: If you have high-resolution observations taken with a telescope 25 cm or bigger, please contact planetary geologist Justin Cowart: His email is Justin (dot) cowart (at) stonybrook (dot) edu or you can find him on Twitter.

Justin has been collecting data on the impact site, and has narrowed the location down to the coordinates 29.47S, 67.77W (+/- 4km):

There's some uncertainty to the exact location due to various effects (like pinpointing the fireball (small gray ellipse in the image above), plus the location of the observers on Earth (larger ellipse)). The uncertainty takes the shape of an ellipse because the impact site is near the limb of the Moon as seen from Earth, and so the landscape is foreshortened there. A small uncertainty in longitude translates into a wider physical area in the east/west direction than north/south.

Also as he points out, as LRO orbits the Moon it takes images with a swath about 5 km wide. If his estimates are off by even a small amount, LRO might miss it!

Interestingly, I talked to Noah Petro, Project Scientist for LRO, and he noted that the impact may have created secondary craters, smaller ones made by debris blown out by the main impact. Those will spread out over a larger area, and are easier to spot, so it's possible that even with a rough location known beforehand the crater can be found. Also, fresh craters look distinct from older ones — they're brighter, and have a bright fresh splash pattern around them — so once it's in LRO's sights it should be relatively easy to spot.

It's not clear how big the crater will be. I've seen some estimates that the rock that hit was probably no more than a dozen kilograms or so, and the crater will be probably 10 meters across. That's small, but hopefully its freshness will make it stand out.

I'll note that I did a live stream myself during the eclipse, but I was using a small spotting 'scope, and as it happens I was fiddling with the pointing right when the asteroid hit! Otherwise, it's possible it would've shown up in my own video. Ah well. I was having a devil of a time keeping my phonecam focused anyway.

Also, a lot of people on Twitter were asking why the impact made a flash when the Moon has no atmosphere. Good question! We see meteors because they burn up in our air, but on the Moon they just slam into the ground. But either way makes a flash.

An impactor is typically moving very rapidly, dozens of kilometers per second. That translates into a lot of energy in its motion (called kinetic energy). Think of it this way: If I toss a marshmallow at you it's easy to stop, but a truck rolling toward you at the same speed is far harder! It takes more energy to stop it. For an impactor, the energy of motion is huge, and when it hits the ground that energy is released. Some of it goes into the surface material, ejecting it and forming the crater. Some small fraction of it goes into light and heat as well, making the flash we see. I've seen estimates that only 0.1% goes into light, but even a ten-kilo rock moving at, say 20 km/sec has the energy of a half ton of TNT exploding.

I find this whole thing wonderful. While such impacts may be common on the Moon, this one has the potential to be different: Because it happened during a widely observed total lunar eclipse a lot of people saw it for themselves, and we may yet get more and better observations of it from the fleet of telescopes taking video at the time.

So if you have good data, let Dr. Cowart know! You can help advance the scientific knowledge we have of our Moon, just because you wanted to see a pretty celestial event. How cool is that?