Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

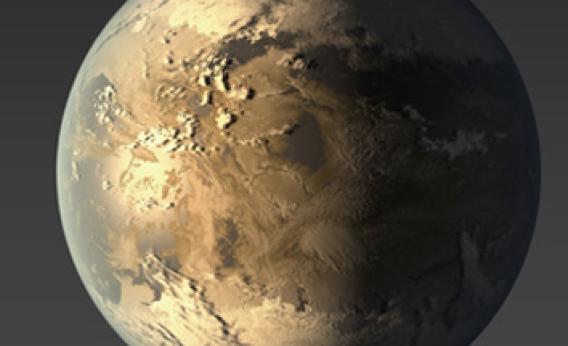

An Astronomical Discovery: Earth-Size Planet Found in Its Star’s Habitable

Zone

I have some cautiously exciting exoplanets news: Astronomers have announced the discovery of a planet that is very nearly the same size as Earth and orbiting its star in the habitable zone—that is, at the right distance from its star to have liquid water on its surface. We don’t know how Earth-like it is, but this shows that we’re edging closer and closer to finding another Earth, and this one is the best bet we’ve found so far.

The planet is called Kepler-186f and was discovered using the Kepler Space Telescope, which was designed to look for planets orbiting other stars. Kepler exploits what’s called the transit method: It stares at 150,000 stars all the time, looking for dips in the amount of light received from every star. The idea is that if a star has planets, and if we see the orbits edge-on, then every time the planet passes between us and its parent star it’ll block an teensy bit of light (usually far less than 1 percent).

This method is extremely powerful—about a thousand planets have been found this way in Kepler data! In fact, most of the planets found this way have been from Kepler. Another cool thing is that if you know how big the star is (and we generally do) then you can also determine the size of the planet by how much light it blocks.

Kepler-186f is one of the big success stories. It’s part of a mini-solar system, a five-planet system orbiting a red dwarf: a smaller, cooler star than the Sun. The other four planets (Kepler-186b-e) are all very roughly Earth-size, but orbit far closer to the star, ranging from 5.1 million kilometers (3.2 million miles) to 16.5 million kilometers (10 million miles)—for comparison, Mercury orbits the Sun at a distance of about 50 million kilometers (31 million miles), so this really is a solar system shrunk down. But even though the star is cooler than the Sun, these planets are close enough to it to be pretty hot; even the farthest of the four previously known would be hot enough to boil water on its surface (assuming it has a surface).

186f is different, though: It orbits farther out, about 53 million kilometers (33 million miles) from the star, where temperatures are more clement. Making some basic assumptions, it lies near the outside edge of the star’s “habitable zone,” where liquid water can easily exist on the surface of a planet. We know of several dozen planets like that in the galaxy so far, but what makes 186f special is its size: it’s only about 1.1 times the size of Earth! Together, these make it potentially the most Earth-like planet we’ve yet found.

I say potentially because honestly we don’t know all that much about it besides its size and distance from its star (and its year—it takes 130 days to orbit the star once). The next things we’d need to know about it are the mass, what its atmosphere is like, and the surface temperature. The gravity of the planet depends on its mass, and in many ways the atmosphere depends on the gravity. Unfortunately, we don’t know either, and we’re unlikely to. The techniques used to find planet masses aren’t up to the task for this planet—the star is too dim to get reliable data. The same is true for any air the planet might have as well. And without that, we don’t really know its surface temperature.

So we don’t know if this planet is like Earth, or more like Venus (with an incredibly thick, poisonous atmosphere that keeps the surface ridiculously hot), or like Mars (with very little air, making it cold). It could be a barren rock, or a fecund water world, or made entirely of Styrofoam peanuts, or some weird thing we haven’t even imagined yet.

Still, our models of how planets form are getting better, and we’re getting a handle on how they behave. According to what we know, it’s most likely that Kepler-186f is a rocky planet like the Earth, with a similar surface gravity. That in turn implies it could have water. But again, we just don’t know, and anything beyond this is speculation; there are a lot of factors in making a planet habitable. As a random one, it may take a magnetic field to make a planet livable. Ours protects us from the constant stream of subatomic particles the Sun emits, which, over several billion years, would have eroded away Earth’s atmosphere. That may be what happened to Mars.

To be fair, I’ll note that there is one planet found before that’s roughly the size of Earth (though bigger than Kepler-186f) and in its star’s habitable zone, but in that case the planet orbits at a distance where it receives about as much heat and light from its star as Venus does from the Sun … and look where that got Venus. Kepler-186f is therefore more likely to be Earth-like than that other planet, though again we can’t be sure with the information we have now.

Still, this is exciting news—after all, one of the main mission objectives of Kepler was to do just this: find an Earth-sized planet in its star’s habitable zone. So, my congrats to the team of astronomers involved: It’s very nice indeed to see a spacecraft achieve its goal! And there’s still lots and lots of data to go through from Kepler. There could easily be many, many more such worlds hidden in the blips of starlight Kepler has returned to Earth.

We’re pretty sure there are billions—billions—of Earth-sized planets in the galaxy. We now know of four that are in their star’s habitable zone (if you include Venus and the other planet I mentioned)… and we also know that some worlds are outside the strict definition of the HZ and yet still have liquid water (Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus).

We’ve only just started looking. Who knows what else is out there?

Tip o’ the Lyot stop to Stephen Kane (one of the astronomers who found this planet, for his gracious help with info; go check out his website, Habitable Zone Gallery) and to the lead author Elisa Quintana.