Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

An Optical Illusion You'll Swear Is Moving. It Isn't.

Kirk: Scotty, you're as good as your word.

Scotty: Aye, sir. The more they overthink the plumbing, the easier it is to stop up the drain.

â Star Trek III: The Search for Spock

Our brains are massively complex machines, constantly processing huge amounts of data from our senses. Our eyes provide most of that input; they send a huge amount of information to the brain, and itâs actually rather astonishing we can figure anything out from it. Given that, our ability to detect motion is pretty amazing. Despite all that noise, if something moves, something changes, our brain targets right on it.

To see motion, you need at least two objects, so that one can move relative to the other. Sometimes, one of those objects is you. If you turn your head, the room youâre sitting in looks like itâs turning the other way. But our brain compensates for that; it âknowsâ itâs moving, so you perceive the room as motionless.

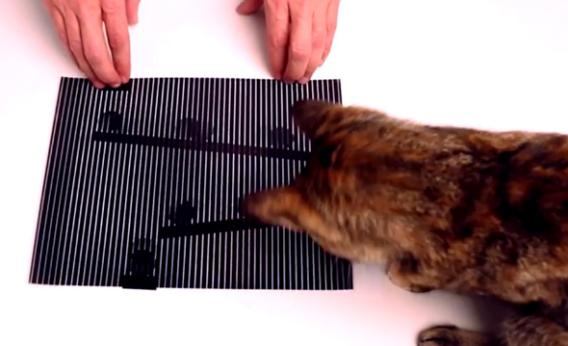

But this works the other way, too: You can make the brain think something is moving even when itâs not. Thatâs the principle behind this wonderful optical illusion video created by brusspup:

Isnât that great? Your brain will swear those drawings are moving, even when you can see they are not. Even the cat was fooled!

This video looks fantastically complicated, but the way it works is actually pretty simple. Basically, itâs fooling your brain into ignoring the thing that is moving, and making it look like the motionless thing is whatâs doing the moving.

To understand this, letâs simplify. Hereâs a diagonal line:

Now imagine you can only see a little bit of that line at one time⦠say, but putting an opaque piece of paper over it that has a narrow, vertical slit in it. If you placed the slit on the left of the line, all youâll see is a bit of the line to the upper left:

Move the paper to the right a bit, and you see the part of the diagonal line thatâs lower:

And more:

The thing is, if you move the paper smoothly to the right, your brain ignores that motion (itâs easy, since the background is a dull smooth field), and instead incorrectly perceives the diagonal line as a square (well, a tiny parallelogram in this case) moving downwards.

Now let's say you have two lines intersecting in an X.

As the slit moves, your brain will see the top square moving down, and the bottom square moving up.

First this:

Then this:

It's hard to see this from my static picture, but you can prove it for yourself! It only takes a minute to make a piece of paper with a slit in it (or to tape some paper together to do the same thing). Grab another sheet, draw stuff on it, and then start tricking your brain. You'll get the picture (hahaha! Ha!).

If you add more slits, the motion gets more complicated. Youâll some parts moving in one direction while others move in another. Change the shape of the lines behind the slits, and you can get fairly complex animations.

Thatâs really all there is to this. For the video, the series of parallel lines are just lots of slits, and the squiggles behind it drawn so that as the slits move, the squiggles appear to make a coherent, moving image. Our eyes track the moving slits, so we perceive them as not moving! And because the slits are evenly spaced, the motion repeats as the next slit in line moves over the same part of the drawing behind it. Your brain sees a cyclical animation, even though the drawing isnât moving at all.

The genius of brusspup is to take this simple idea and create complex, engaging motion that coalesces into a coherent scene. That makes it even easier to fool our brains; it loves a good story, and focuses on it. We see those circles moving, the Pac-Man eating the drops, the skull rotating. He has another video with more examples, too.

My favorite part of all of this is that it shows us that what we think is happening is rarely what is really happening. Everything around us gets filtered through our senses and then totally bollixed up by our brain. Itâs a complete mess, but weâre used to it. Weâve adapted to it (just as itâs been adapted by evolution), so even though it works to keep us alive and aware of whatâs going on around us, it can be quite easily fooled.

Thatâs something your brain needs to know about itself.

Tip oâ the Necker cube to Gizmodo.