Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

These Minion-like animals aren’t our ancestors. So we’re back to evolutionary square one

Prehistory was truly terrifying.

Getting from single-celled life to human beings required a lot of branches on the evolutionary tree. One of those branches, which is estimated to have occurred about 670 million years ago, is the separation of protostomes and deuterostomes. That branching resulted in nematodes and arthropods on the protostome side and everything from hagfish to humans on the deuterostome side.

Paleontologists are interested in finding evidence of that early diversification in the fossil record and a study published in 2017 suggested we had succeeded. Scientists had identified a sub-millimeter sized animal called Saccorhytus coronarius which appeared to be the earliest known deuterostome, dating back 540 million years ago. Despite lacking an anus — a characteristic which is typical of deuterostomes — scientists categorized based on a series of holes along its surface which could have served as orifices for waste removal. Unfortunately, it seems that paleontologists will have to go back to the drawing board after an updated analysis revealed Saccorhytus coronarius likely isn’t a deuterostome after all.

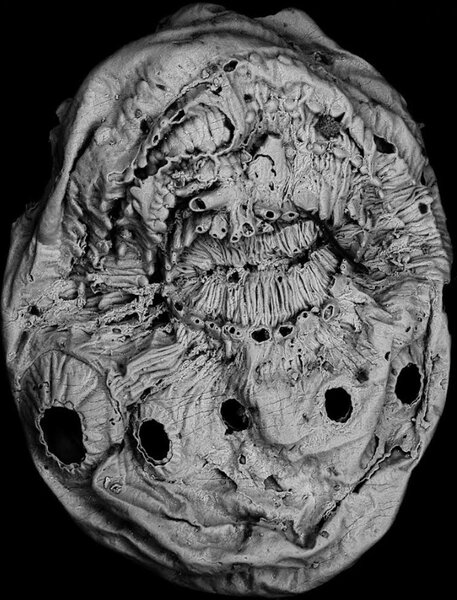

Shuhai Xiao from the Department of Geosciences at Virginia Tech, and colleagues, collected hundreds of specimens and completed a new reconstruction which undoes the previous understanding. Their findings, published in the journal Nature, reveal that the surface holes weren’t holes at all but instead were the fractured remnants of spikes.

“The previous conclusion was based on broken specimens and the breakage made an artifact structure that superficially resembled structures that occur in other deuterostomes, on our side of the tree. It has many spines but during transportation a lot of the spines were broken and produced hole openings,” Xiao told SYFY WIRE.

The holes around the body were the only feature which supported the hypothesis that they were a member of the deuterostome family. Without them, there’s nothing else about this animal which supports that conclusion.

“We can’t blame the previous researchers because the fossils are very rare. We spent a lot of time and dissolved tons of rocks to extract the material we presented,” Xiao said.

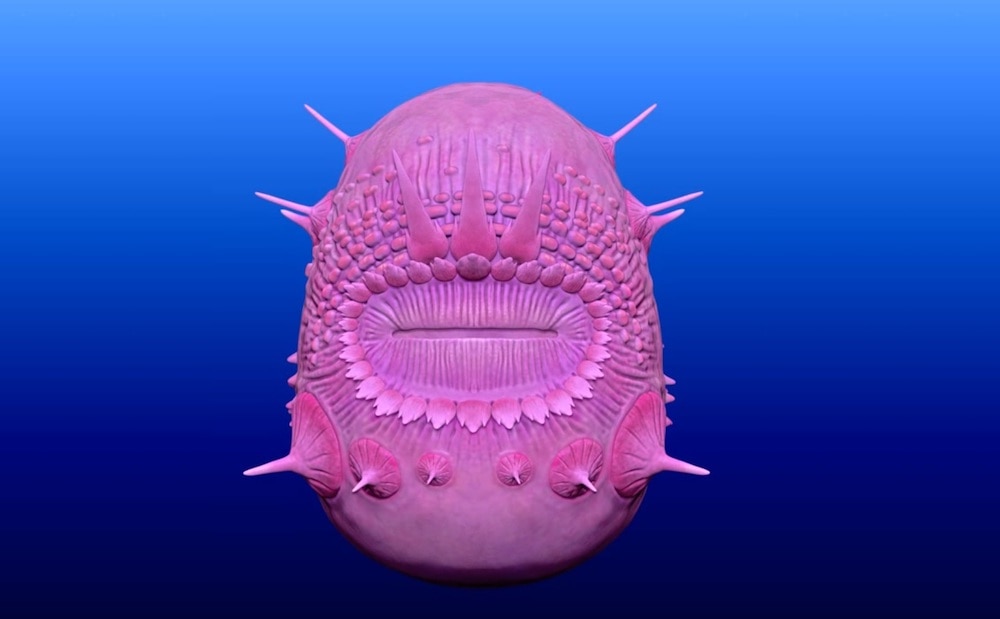

Getting an updated picture of these creatures required a considerable reconstruction of their bodies. Not only were they small and prone to fracturing after death, but their bodies also deflated and deformed like a punctured basketball, all of which caused considerable changes to their surface structures. To reconstruct them, scientists had to effectively re-inflate their structures in their models to recover their surface features. They also benefited from having hundreds of specimens, something the previous study didn’t have, which allowed them to make comparisons and fill in the gaps of individual animals.

What they found were nearly spherical animals superficially resembling Minions, covered in spikes and with a comparatively large mouth opening. That opening would have performed double duty, taking in food and excreting waste.

“They’re so small they could have suspended themselves in the water column, but more likely they lurked within the interstitial space between sand grains where they fed on particulate organic carbon. The spines might have protected them against predators, helped them to suspend in the water column, or may have been used as sensory organs,” Xiao said.

None of their internal structures were preserved but scientists believe they must have had a gut, a neural system, and musculature. That’s supported by their bilateral symmetry and inferences from other similar animals. While this new study answered a lot of questions about what sorts of animals they were, it opened up even more questions about our own ancestral history.

"It’s interesting because we would expect to find deuterostomes at that age. This was the oldest one we had found so if it’s not a deuterostome we’re back at square one," Xiao said. "Like many scientific discoveries, you make some progress, and it raises even more questions. Where are the deuterostomes in the fossil record?"

We know that the two groups diverged around this time, and Saccorhytus is evidence that protostomes were swimming or digging in the world’s oceans. To date, however, the branch which leads to humans and our closest relatives continues to elude us.

That said, there’s some comfort in knowing we didn’t descend from an animal covered in spikes which defecated from its mouth.