Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Is the 50-year-old ghost of Apollo 13 warning us not to rush to the Moon?

With the future of the next Moon landing beginning to look more and and more uncertain as the COVID-19 epidemic pushes developments back, the question hanging in space is whether that is still too soon.

Apollo 13 will forever be known as the lunar mission that almost didn’t survive. Today, on the 50th anniversary of its safe return, some are unsure about whether Artemis — NASA's Moon mission eyed to start launching in 2024 — is trying to take off too fast. The infamous ride wasn’t the first glitch experienced by Apollo-era spacecraft headed to the Moon. Even on Apollo 11, Neil Armstrong just barely decided where to touch down before the lunar lander ran out of fuel. The Saturn 5 rocket that launched Apollo 12 was struck by lightning, which screwed with the electronics, though the spacecraft still made it out of the atmosphere somehow.

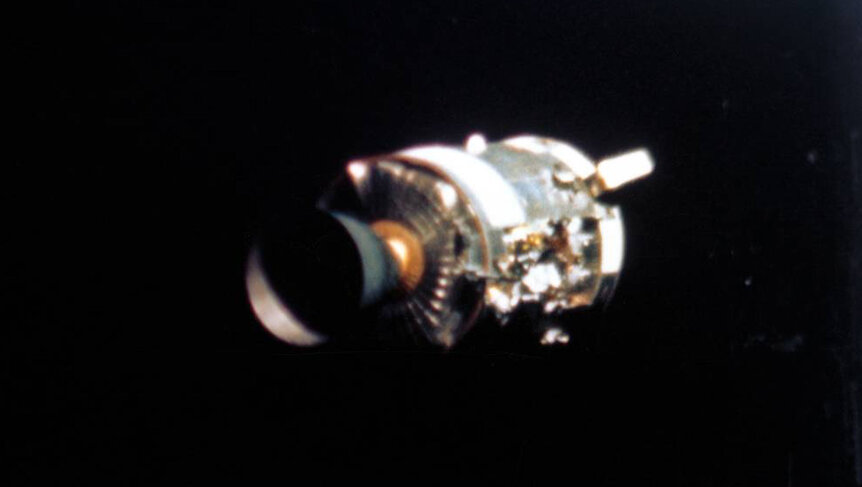

Unlike its predecessor, Apollo 13 didn't make it to the Moon. The explosion that blew off a chunk of the spacecraft is now bringing up serious questions about whether safety measures have advanced enough since the Apollo Era — and if we really are ready to return to lunar turf.

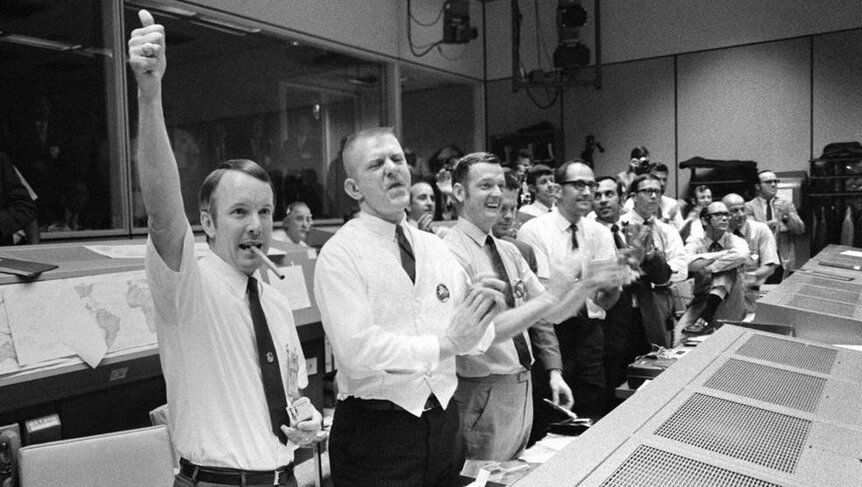

“Spaceflight, you’re operating in a pretty difficult environment,” Gene Kranz, the flight director in charge of mission control for Apollo 13, told The New York Times. “For the first minutes, I thought, ‘This is a minor electrical problem’ … then another controller said the crew reported a pretty big bang.”

What had gone unnoticed were the damaged wires inside one of the oxygen tanks of the service module, which propels the spacecraft and provides it with electrical power. Astronaut John L. Swigert Jr. was piloting the command module. Mission control asked him to take a minute to whisk around the freezing hydrogen and oxygen in the propellant tanks, a routine “cryo stir” that prevents the propellants from separating, which would mess with the pressure reading. He knew something was off when the spacecraft started to shake and warning lights blazed.

You probably remember that scene from Apollo 13 when Tom Hanks' Captain James A. Lovell Jr. contacts mission control, famously saying “Houston, we have a problem.”

When Swigert flipped the switch to start the procedure, a spark flew. That spark set the insulation of the faulty wires on fire, and soon the tank burst. The other oxygen tank was severely damaged. The command module was on its last breath, so the astronauts crowded into the lunar module. Back on Earth, engineers were able to do enough damage control to restart the command module with the dregs of power that were left, and also change the trajectory of the spacecraft toward our planet (which was 200,000 miles away). Apollo 13’s crew would end up splashing down into the Pacific Ocean.

Had this happened when the astronauts had already landed on the Moon, Swigert would have been lost in lunar orbit on the separated command module, with crewmates Lovell and Fred Haise left stranded on the surface.

Of course, that doesn't mean that Artemis will end up as ticking time bomb. Rockets have gotten a major upgrade since the ‘60s and ‘70s. Lighting probably won’t strike twice now that there are stricter launch rules, and tech more competent at finding out out if too much electrical charge is in the atmosphere. The problem is that NASA hasn’t yet figured out all of the details of how the upcoming moon landing should go. What they do know is that they’ve got the SLS, which is really a leveled-up version of the Saturn 5 that launched the Apollo missions, and the command module, which is the Orion crew capsule. It can operate autonomously but can be switched over to manual mode.

There is still one critical thing missing. NASA has not yet chosen the lander. They are currently accepting proposals from commercial entities (think Boeing and Blue Origin), but you can’t come up with a landing plan and catastrophe-proof it in just days. NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine recently decided to change the original launch plan because it had too many phases, which could only mean more opportunities for things to go wrong. The involvement of the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway was going to complicate things.

NASA’s associate administrator for human exploration and operations, Douglas L. Loverro, is simplifying those plans to factor out the Lunar Gateway.

So could Artemis not be ready to take that giant leap by 2024? It depends. At least, in the worst-case scenario, there are much faster communications systems than there were in 1970, and a small camera deep in the spacecraft will alert astronauts and Mission Control of any damage and the extent of that damage. Unfortunately, fast-thinking computer brains bring on new problems. A spacecraft that can do things autonomously is still prone to computer errors. If the dreaded blue screen happens on Earth, it can happen in space.

For anyone hoping to stream the same experience their parents and grandparents had on on July 20, 1969, when the staticky voice of Neil Armstrong was transmitted on black-and-white TV screens across the Earth, it might be a while.

(via The New York Times/NASA)