Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Mercury's diamond covered surface makes it the crown jewel of the solar system

All we need is a spaceship and a sifter and we'll be rich!

Getting our hands on diamonds here on Earth often involves digging deep underground to find the places where they form. On Mercury, it might be as easy as bending over.

Kevin Cannon, Planetary Scientist from the Department of Geology and Geological Engineering and Center for Space Resources at the Colorado School of Mines, crafted a series of simulations of Mercury’s surface which show it could be littered with diamond debris. The findings were presented at the 53rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference.

On Earth, diamonds are created through intense pressure in the mantle. The collective weight of all the rock overhead presses down on collections of carbon, squeezing them into crystallized diamonds, but heat and pressure come in various forms throughout the universe, and Mercury might be a perfect diamond construction site fueled by asteroid impacts.

“The Apollo missions actually went to surfaces with a certain number of craters per area and came up with ages for those. We’ve built up this chronology of the impact rate which we map onto different planets by extrapolating how much stuff we think hit Mercury for every asteroid that hit the Moon,” Cannon told SYFY WIRE.

Using that chronology, he was able to come up with an estimated rate of impacts over the last 4.5 billion years, since the solar system formed. Knowing the rate of impact on Mercury’s surface was only one piece of the puzzle, it’s also important to understand the special circumstances of Mercury’s crust.

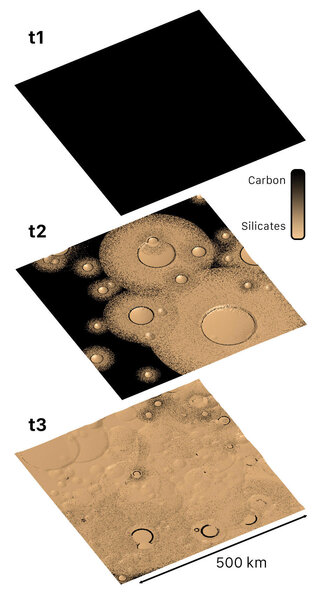

It’s thought that early in the life of Mercury it would have had a global magma ocean. It also has a unique chemistry which is highly reduced, meaning there wasn’t a lot of oxygen, which allowed graphite to crystallize in the magma. All of that graphite would have floated to the surface, creating a graphite flotation crust. In essence, much of Mercury’s surface had a very high percentage of pure carbon, just waiting for some pressure to turn it into diamond. Cue the impacts.

Assuming a graphite crust that's 300 meters thick, the expected impact rate should have produced a diamond hoard roughly 16 times larger than what we have on Earth. Diamonds produced through this method, however, wouldn’t necessarily make for good jewelry.

“Diamonds formed through impact shock won’t be large, clear crystals. We know that because we find them in different meteorites. They’re going to be a lot smaller. They’re going to be dark, cloudy, and probably mixed with all different carbon phases. Definitely not something you could polish up and put on a ring,” Cannon said.

The violent impact process would transform graphite into diamond and scatter it like a dust over the surface where it would mix into the soil. Bending down to pick up a handful of Mercurian dirt might net you some diamond dust, but you’d need a microscope to find it.

The models also show that Mercury is no longer producing diamonds, at least not at the rate it once was. The heyday of diamond production on the closest planet to the Sun ended about a billion years after the solar system formed, owing to a change in conditions both on its surface and in the solar system at large.

“We think the impact rate in the solar system fell off dramatically after about a billion years. Fewer impacts means less graphite can be converted. Also, once you’ve turned a certain amount of graphite into diamonds, there’s no more of it around to be converted,” Cannon said.

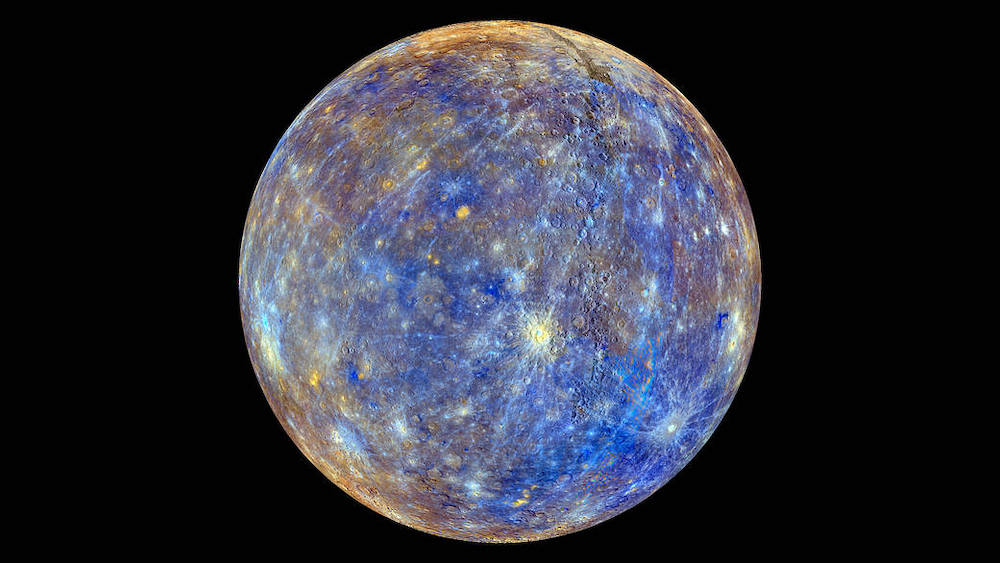

Still, there’s plenty of diamond to go around if an enterprising space agency got up the gumption to go there and find it. The BepiColombo, a joint mission by the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency could give us a better idea of Mercury’s surface composition. Many a planetary scientist, Cannon among them, advocates for sending a lander or rover to the surface.

Mercury’s diamonds are safe, for now, but it never hurts to send a robot to do a little prospecting.