Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Bacteria has been attacking us for two billion years, before we had mitochondria

They were running at us before we even had our evolutionary shoes on.

We often think of nature in the modern world as being red in tooth and claw, a constant struggle for survival between predator and prey. Conversely, life on the early Earth, before the evolution of complex plants and animals seems peaceful by comparison. Just single celled organisms floating around in the water, gathering energy from the Sun.

It turns out, however, the struggle for survival started much earlier than most of us consider. Almost from the very beginning our distant ancestors, early eukaryotes, were being attacked by predatory bacteria.

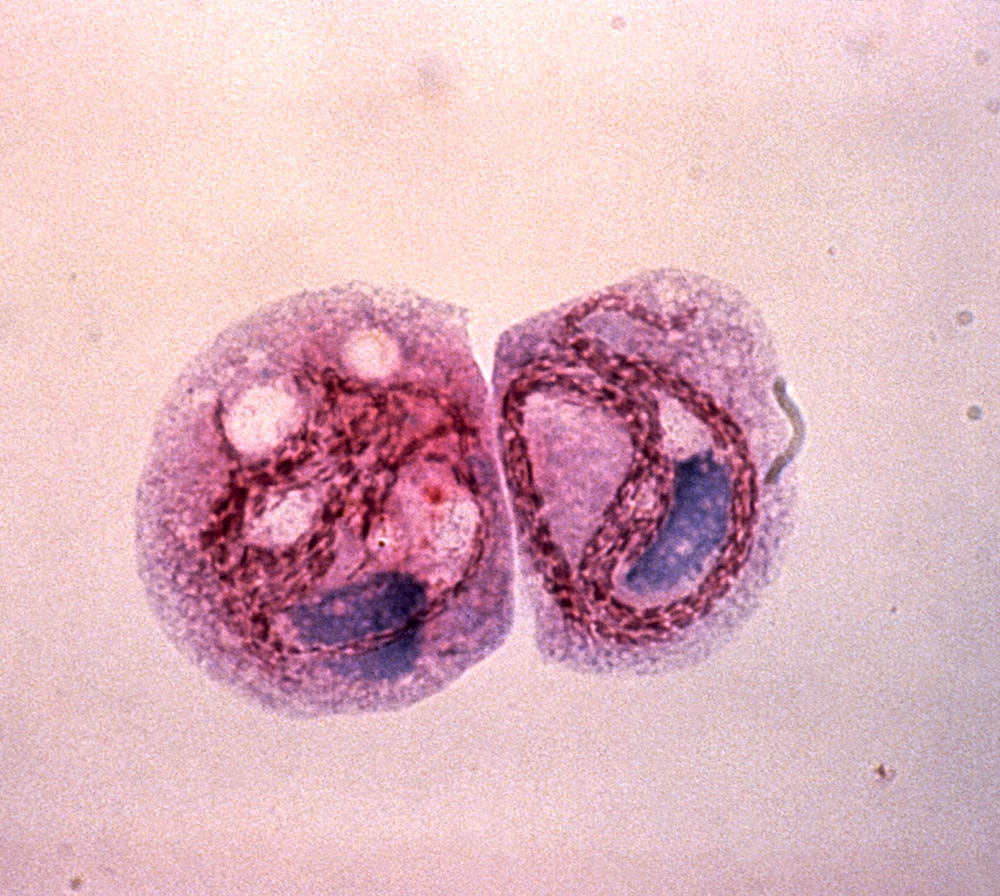

In a new study published in Molecular Biology and Evolution, Lionel Guy from the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology at Uppsala University, and colleagues, peered two billion years into the past at Earth’s early microbial life. They found that even before eukaryotes were fully formed, they were under siege from legionellales, an ancestor of modern legionella, the bacteria which causes Legionnaires disease.

“To be able to look into genetic sequences and see back to two billion years ago is incredible,” Guy told SYFY WIRE. “Two billion years is roughly half of all life on Earth. We hope we can go back further to the ultimate question of what was the last universal common ancestor.”

Looking back into the distant past of life on Earth is especially challenging because at that time life was incredibly simple. It hadn’t yet developed hard parts which could be fossilized and leave a clear record for us to find.

To get around this problem, scientists use phylogenetic trees which take existing relatives of a species and use their traits and genes to build a timeline backward into the past. They were also helped by a relative of legionellales which didn’t leave fossils but did leave hints of its presence in the geologic record.

“There is a bacteria closely related to legionellales called chromatiaceae, also known as purple sulfur bacteria, and they leave pigments. We have found traces in rocks which are 1.64 billion years old, and we can use those to calibrate our time trees to find roughly where legionellales belongs,” Guy said.

They were able to date the common ancestor of all legionella to about two billion years ago, a time when eukaryotes were still finding their feet and interacting with bacteria. Most bacterial interactions at the time benefited eukaryotes. The bacteria were consumed, destroyed, and used as a fuel source. Legionellales hijacked that process for its own purposes.

“They would still be consumed and end up inside the cell, but instead of meeting their fate they had a way to evade,” Guy said.

Legionellales had a molecular syringe they would use to inject proteins into the host cell’s cytoplasm and change their behavior. Ordinarily, when a bacterium is consumed by a cell, interactions between the vacuole and lysosomes result in low pH which destroys and essentially digests the bacteria. Legionellales arrested that process, arresting the normal interactions, and used the cell to reproduce.

It’s unclear exactly where legionellales came from, but it’s likely it didn’t exist, or at least wasn’t attacking cells, prior to the emergence of eukaryotes. Today there are countless lineages of legionellales, all of which attack eukaryotes. That likely wouldn’t be possible if they were around and behaving in the same way before.

“They would all have had to evolve a way to get into eukaryotes when they showed up. That’s very unlikely because they use exactly the same tools. It would require that you infer a lot of convergent evolution. It’s not impossible, but it’s unlikely,” Guy said.

Whatever their strategy, it has been incredibly successful. Modern diseases like Legionnaires are only the latest battle in a war which has raged for two billion years. But things could change.

“There is a wide variety of ecological types. Some of them are purely parasitic and some of them are mutualistic, and there are a lot of transitions within those groups,” Guy said. “How could we tame bacteria? How do we change them from parasitic to being helpful?”

Studying ancient bacteria like legionellales not only provides a clearer picture of how life evolved on our planet but could give us the tools to turn the tide of the war and make allies of our tiniest enemies.