Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

These two asteroids are extremely young… and used to be just one asteroid

An asteroid flew itself apart, making new rocks 2019 PR2 and QR6.

Congratulations! It's a bouncing baby asteroid!

Wait... wait... it's twins!

Well, kinda.

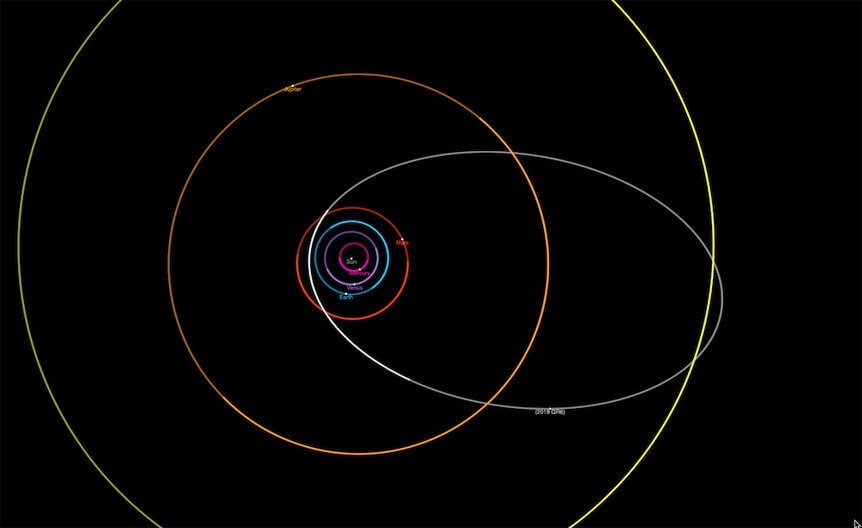

In 2019, two different asteroids were discovered by two different telescopic sky surveys: the Pan-STARRS survey found 2019 PR2, and the Catalina Sky Survey found 2019 QR6. These two space rocks were very close together in the sky, only about a degree apart — about twice the width of the full Moon on the sky — and it didn't take long to figure out they were on very similar orbits, which is unusual (link to paper).

Further observations showed that the orbits weren't just similar, they were virtually identical. That can't be coincidence. In fact, the most likely scenario to explain them is that they used to be one asteroid that split in half, so that's cool. Their proximity to each other — about a million kilometers apart when they were discovered — indicated that if they were born from one rock that broke apart it must've been pretty recent, too, as little as 300 years ago.

If so, this makes them the youngest asteroid pair known.

The highly elliptical orbits of PR2 and QR6 take from just inside the orbit of Mars to a bit past Saturn's. They get close enough to the Sun to technically be considered Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs), but they don't get terribly close to Earth, never approaching us nearer than about 30 million kilometers, so they're no threat to us.

The colors of the two asteroids are also very similar, and indicate they are probably D-type asteroids, which are relatively rare among NEAs, again more evidence they're a pair. These asteroids tend to be dark, reflecting roughly 2% of the sunlight that hits them, making them considerably darker than charcoal. Given that, their distance from Earth, and how bright they appear, PR2 is about a kilometer wide, and QR6 about half that.

So how can an asteroid split in half? An impact large enough to do this would likely just create a lot of debris, so that's unlikely. Instead, the astronomers who have studied them think the parent asteroid literally spun itself apart. Even then, though it had help.

There is a weird process small asteroids undergo called the YORP effect, named after the scientists who figured it out, Yarkovsky, O'Keefe, Radzievskii, and Paddack. Sunlight warms an asteroid, which then radiates that heat away as infrared light. The light is usually emitted at an angle to the surface due to irregularities like craters, boulder, and so on. But light has momentum, so this YORP emission torques the asteroid, changing its spin. Over time, the spin can increase so much that the centrifugal force can become quite strong, enough to overcome the structural integrity of the asteroid itself. When that happens it flies apart.

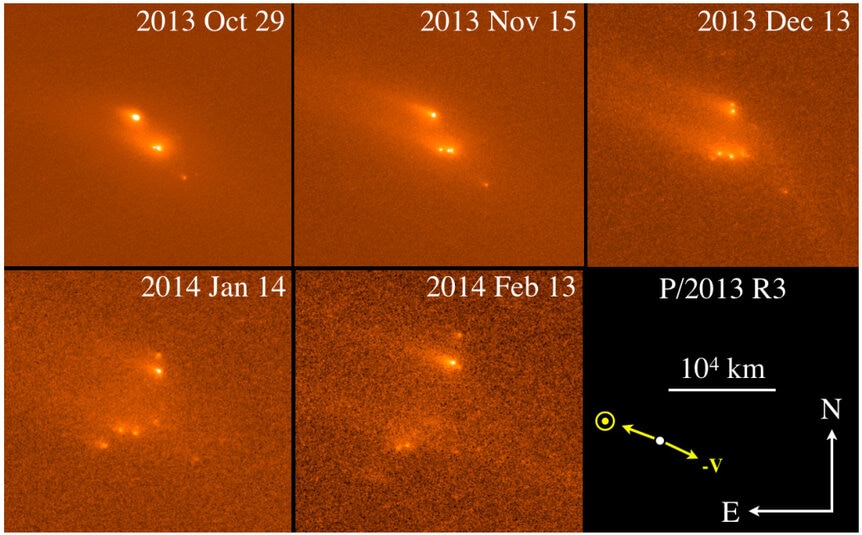

We've actually seen this happen many times, with asteroids suddenly breaking apart. It's probably the single most common reasons asteroids disintegrate, and so is the prime suspect in the creation of 2019 QR6 and PR2 from one previous asteroid.

But there's a problem. Using the current orbital shapes, the astronomers ran simulations of the asteroids' location back in time, and — assuming that gravity was the only force acting on them — no matter what they did the asteroids never got very close together. But at some point in the past their mutual distance must have been 0, so this can't be right.

So then they looked at non-gravitational forces. The YORP effect didn't change things much, so then they wondered if the asteroids had ices in them, like water ice or frozen carbon monoxide. After the YORP effect splits the parent asteroid, these buried ices would be exposed to sunlight, and turn directly into a gas. That would act like a rocket motor on them, accelerating them away from each other.

They ran models to see how much force that would add to the rocks, and found that this worked: If the parent body split about 300 years ago and the two then jetted away from each other, the orbits work out.

So if they're correct, sometime around the time King Frederic I of Sweden was crowned, an asteroid that had been spinning faster and faster for centuries finally had enough. It cracked in two, with one piece about twice the size of the other, and the two pieces for a time accelerated away from each other under the force of their insides vaporizing. This moved the new asteroids apart, though they stayed on almost identical orbits.

That all makes sense scientifically, except no gas activity is currently seen around PR, despite being close enough to the Sun that any exposed ice should turn to gas and be visible during the observations. That's a little weird, and not easy to explain. Maybe they didn't have much ice, and it ran out after 300 years. Maybe the parent body wasn't an asteroid at all, but instead was a dead comet, one that ran out of surface gas and stopped generating activity until it split. It's not clear, and more observations definitely need to be made.

Whatever its origin story, it's pretty clear 2019 QR6 and PR2 are siblings, born literally from the body of the same parent three centuries past, whatever that object was. And that makes them they youngest asteroid pair known.

Welcome to the family!