Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

So is there liquid water under the Martian ice cap or not?

Two papers come out nearly simultaneously arguing both sides.

So, is there liquid water in a subglacial lake under the south polar cap of Mars or not?

Given the brutally cold sub-freezing temperatures on Mars, especially at the south pole, you'd think the answer would obviously be no. But it's not at all that clear, and two papers came out this week arguing on opposite sides of the idea.

Seriously. This was a press release headline on Monday: "Hope for Present-Day Martian Groundwater Dries Up."

Here is the headline from Tuesday: "SwRI Scientist Helps Confirm Liquid Water Beneath Martian South Polar Cap."

So, yeah. But ooooo, controversy! That makes for fun science. Let's dive in.

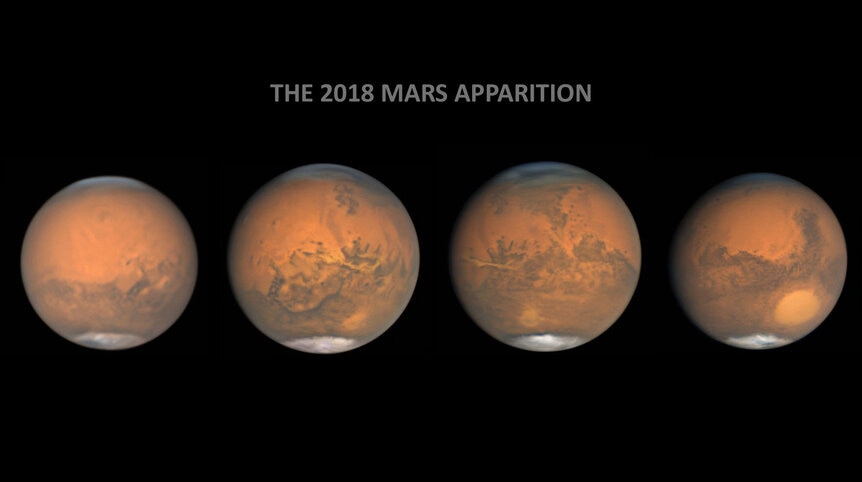

In 2018 some planetary scientists made an astonishing announcement: Using ground-penetrating radar on board the European Space Agency's Mars Express spacecraft, they had found evidence for a lake of liquid water under the south polar cap. Not long after, they announced even more evidence of water under the ice.

At the time of the first announcement I was skeptical but leaning toward it being real, saying,

Let me be clear up front: The evidence is quite good, but not 100% conclusive. There are caveats, which I'll explain below. But looking over their work, I have to admit this looks (ironically) solid. If I had to bet, I'd say they have indeed found a shallow but wide lake of liquid water buried deep under the Martian surface.

If you had taken me up on that bet at the time I would've paid up in 2021. That's when another team of scientists looked at the data and showed that other materials could've caused the radar signal that the first team interpreted as water, and these materials are common on Mars. That makes it seem less likely that water was the culprit.

On Monday, January 24, 2022, my bet-losing seemed to be affirmed. A third team of scientists looked at the data and did some clever modeling (link to paper), showing that volcanic rock — common on Mars — overlaid by ice would produce this same water-like signal.

But then on Tuesday I would've sent you a text to pay me back. A team of scientists, many of whom were on the original team that made the first announcement in 2018, say that yes indeedy very briny water could explain the observations (link to paper).

So who's right? Yes, good question. Let's step back a bit to see what's what.

I describe how this works in my original article, but in a nutshell Mars Express has an instrument on board called the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS). It bounces signals off the surface of the Red Planet to map the topography, but some of that radar can penetrate ice. The south pole of Mars has an extensive cap of water ice on it, more than 3 kilometers deep in some places. In one spot, though, and later more places, the radar return from MARSIS was brighter than expected from just ice. This bright layer was consistent with it being a lake of briny water, though a very shallow one less than a meter thick and 20 km across.

But then the second team looked at other materials that could reflect radar in the same way, including clays, metal-bearing minerals, and very salty ice. All of these are common on Mars, while you need special conditions to keep water liquid that close to the surface — very high salinity, a sub-surface heat source like magma, and so on — so the original claim got weaker.

The third team that published Monday did something clever: They looked at pre-existing MARSIS radar reflection maps of other regions of Mars, which can be mapped to known terrains like volcanic regions, plains, and so on. They can then created models of what those terrains would look like to MARSIS if they were covered in ice like that at the Martian south pole. While the exact mineral compositions of those areas may not be known, their reflectivities are, so they can still be used to see what the instrument would see if they were buried under ice.

What they found is that some volcanic rock would give very similar results if it were buried under a kilometer of ice. Volcanoes are everywhere on Mars, so it's not too big an extrapolation to think that this same kind of rock may exist under the austral ice. This weakens the case for water.

And now, a day later, a paper is published saying hang on, not so fast. Results from a lab experiment show that water can be a liquid even at the -75°C (-100°F) temperatures at the base of the Martian ice, if it's a briny solution of perchlorates — a chemical compound made of chlorine and oxygen, which is common on Mars. NASA's Phoenix lander detected it on the surface of Mars years ago. In that case the water isn't so much a subsurface lake as it is existing in gaps between grains of ice and rock under the polar cap — think of it like the water on a beach between the grains of sand after a wave recedes.

So who's right? Has the claim of liquid water dried up or is it confirmed?

Here's my take: Neither.

Claiming the water is definitely there is not supported by the evidence. However, saying it's not there isn't supported either!

What can be said is that under some conditions, liquid water can exist in these places, but the observations are also consistent with a layer of various minerals and rocks, so there's not enough to make a firm claim either way.

Arguments can be made for and against both ways. Yes, volcanic rock works, but the kind they found is relatively rare on Mars, only on about 2% of the surface. That makes it seem unlikely that this is the cause. Yes, perchlorate brines can keep water liquid at very low temperatures, but then you need something deeper under the surface — possible a pool of magma — to keep the temperature even that high, and you have to be careful when using special circumstances to explain an observation.

So right now we have to remain skeptical about the science — as we always should be! — until further evidence comes in further supporting one claim or another. And, as we've seen, even then we should keep options open.

I'll note that one reason the idea of liquid water is exciting is the prospect for Martian life, but now both claims make that less likely. If the water's not there we're done. But if it is and loaded with perchlorates that's bad; those tend to tear apart organic molecules. Either way, life is pretty unlikely under the austral Martian ice.

But the ultimate goal isn't necessarily to prove one thing or another. The actual endgame here is to understand Mars better. Whatever the outcome, that overarching purpose will be achieved.