Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Bad Astronomy Movie Review: Gravity

Let’s get this out of the way immediately, so there’s no confusion: The movie Gravity (which opens today) is incredible. It was intense, it was tense, it was thrilling. Go see it. In fact—and I can’t believe I’m writing this—go see it immediately, and if you can, watch it in 3-D. I loved it.

But that love is not without its (minor) reservations. While I can wholeheartedly recommend it—I spent much of it literally on the edge of my seat—there were some things that, as a world-class nitpicky übernerd, I must point out. But I’ll note up front that nothing I whinge about below will detract from the experience of the movie itself. Seriously. It sets the bar for what movies can look like now. Go see it.

What follows below are spoilers, so fairly warned be thee, says I. Let me add that this is not your standard movie review; if you want thematic dissection and all that, then go read my colleague Dana Steven’s piece on Slate. With me, you get science analysis.

Plot Boiler

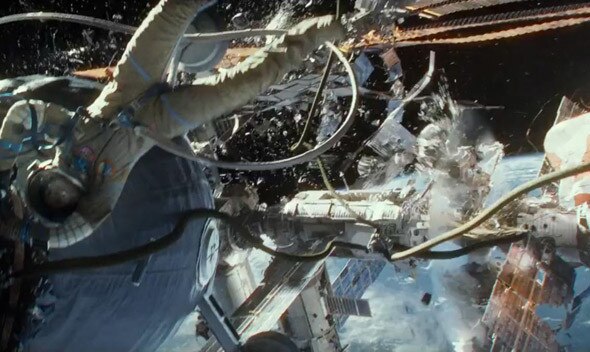

The plot of the movie can be summed up pretty briefly. Sandra Bullock and George Clooney portray astronauts orbiting the Earth on a routine extravehicular activity mission when a call comes from NASA: A Russian missile has destroyed a satellite, and the debris is headed their way at several kilometers per second. Before they can return to their Shuttle Orbiter, the shrapnel flies past, destroying the spacecraft and killing the crew. Clooney and Bullock make their way to the International Space Station, which is also damaged. Clooney is out of fuel in his Manned Maneuvering Unit and sacrifices himself to save Bullock. She uses a Russian Soyuz berthed to the ISS to get to the Chinese space station, where she finds a re-entry rocket capable of getting her back to Earth. But will she make it?

I won’t spoil the very end for you, because it was very well done. I’ll note that this is pretty much it for the plot—it’s thin, but you probably won’t notice.

That’s because the graphics really are all that. I mean, seriously: The special effects are superb. I generally shy away from movies that are all effects and no plot, but the immersive directing coupled with flawless effects—especially with the 3-D—was so compelling that I honestly felt the simple plot was not a concern as the movie unfolded. The drama and urgency were so riveting that I was essentially living in the moment, just experiencing the movie.

Dork Star

Still. There were some distractions in the form of scientific missteps. I’ll go over a few below, but I want to make myself very clear: My days of nitpicking a movie’s errors to death just because I can are behind me. The story lives or dies on the story, not whatever shortcuts it may need to take to move that story along, as long as those shortcuts don’t leap out and bite you on the nose. The plot of Gravity, unfortunately, does rely on some pivotal science boo-boos, but I understand sacrifices have to be made sometimes for the sake of the movie itself—without them, there’s no movie at all. And I’m far more willing to be forgiving when it’s clear a huge effort was made to get as much right as possible, which is obviously what director Alfonso Cuarón did (an interview at Collect Space confirms all this). The attention to some details was staggering.

So, let me push my glasses up my nose, hike up my flood pants, and blow my nose stentoriously. Let’s get to the glavin.

Orbital Mechanical Breakdown

The overall villain in the movie is not a human and not even the eponymous gravity. Not directly, at least: The true antagonist is orbital mechanics. It comes into play when the satellite debris first swarms past the astronauts and rears its Newtonian head again and again throughout the movie when the astronauts make their way to the ISS and then push on to the Chinese space station Tiangong.

The thing is, well … this won’t work. The problem is that most folks think of space as just having no gravity, so you can jet off to wherever you need to go by aiming yourself at your target and pushing off, like someone sliding on ice. But it doesn’t work that way.

The reason is that there is gravity in orbit! The Earth’s. And objects orbiting the Earth are moving at high velocity, many kilometers per second, to stay in orbit. If you want to get from Point A to Point B you can’t just be at the right place at the right time; you need to match velocities as well. If the two objects are in different orbits, that gets a lot harder. Orbital velocity depends on altitude, so objects at different heights move at vastly different speeds, adding up to many hundreds if not thousands of kilometers per hour. The orbits can be tilted with respect to one another, making it hard to match direction. The shapes of the orbits can be different, too, again complicating a rendezvous.

And in fact, Hubble and the ISS have very different orbits; Hubble orbits the Earth roughly 200 kilometers (125 miles) higher up than the station. A rough calculation shows it orbits about 110 meters per second slower, then—250 miles per hour. Clooney would have a pretty hard time putting the pedal to the metal to get up to that kind of speed in his Manned Maneuvering Unit. (The “jet pack” he has in the movie—I’ll note the MMU is a real device but has nowhere near that kind of oomph; it can only accelerate one person to about 25 meters per second, and remember Clooney was dragging Bullock along for the ride as well.)

Also, the two objects have orbits tipped at wildly different angles (Hubble is 28.5 degrees, while ISS is at 51.6 degrees). Think of it this way: Two cars can be going at the same speed, but if they are at an angle to each other, jumping from one to another is hard, especially if one’s heading east while the other is heading northeast (and you have to jump off an overpass at the same time). At a relative speed of 250 mph, that’s suicide.

Same for Tiangong: The orbital height of the Chinese station is about the same as that of ISS, but the orbits are inclined by about 10 degrees. Matching orbits using just the soft landing rockets on the Soyuz (again, a real thing!) wouldn’t work.

But to be clear, without these plot points, we’d have no movie. It’s fun to think about afterward, but during the movie I’m OK with it.

Let It Go, Man

Another significant plot point happens when Clooney and Bullock reach ISS. Still attached by a tether, they have a hard time finding a grip on the station to stop themselves. Eventually, Bullock’s leg gets tangled in the parachute shroud line from the Soyuz escape capsule. Its hold is tenuous, and she struggles to hold on to Clooney as he is pulled away from her. As her leg starts to slip, Clooney unclips his tether and falls away to his doom, saving her in the process.

Except, well, not so much. The thing is, they very clearly show that when Bullock’s leg got tangled up in the shroud line, both her and Clooney’s velocity relative to the space station was zero. They had stopped.

On Earth, if one person is hanging by a rope and holding on to a second person, yeah, gravity is pulling them both down, the upper person bearing the weight of the lower one. If the upper person lets go, the other falls away. But in orbit, they’re in free-fall. Gravity wasn’t pulling Clooney away from Bullock; there were essentially no forces on him at all, so he had no weight for Bullock to bear! All she had to do was give the tether a gentle tug and Clooney would’ve been safely pulled toward her. Literally an ounce of force applied for a few seconds would’ve been enough. They could’ve both then used the shroud lines to pull themselves to the station.

This is a case where our “common sense” doesn’t work, because we live immersed in gravity, pulled toward the center of the Earth, supported by the ground. In space, things are different. During that scene, knowing what I know, all I could do was scream in my head “CLOONEY DOESN’T HAVE TO DIE!” but it was to no avail. My publicly admitted man-crush on Clooney plus my not-so-inner physics nerd made that scene hard to watch.

Ad Absurdum

Of course, there were lots of other things, most too trivial to spend time on.

- We see the bodies of the dead shuttle crew, frozen, when in reality that would take hours to happen. (Think about it: How long does it take a steak to even get frost on it when you put it in the freezer?)

- When Bullock’s decelerating in Earth’s atmosphere, her helmet is still floating in the capsule, when there would’ve been a healthy force pinning it to the back wall.

- Her antics using the fire extinguisher to match velocities with Tiangong were probably impossible; holding it too far from her center of mass meant it would’ve sent her rapidly tumbling every time she used it—plus she had to face away from the station, making it impossible to see her target while she was thrusting. (On the other hand, her not bracing herself to put out the fire and subsequently flying around was a great touch.)

- The cascade effect of orbital debris slamming into other satellites and making more debris is correct, but the debris will stay on roughly the same orbit it started on. That means the satellites making the debris would have to have orbits that intersect that of Hubble and ISS, and that sort of thing is specifically avoided in real life, for this very reason.

- Speaking of which, I’m not sure shrapnel hitting the robot arm would cause it to go flying and spinning off. The impact is very high speed, and I’m not sure much momentum would transfer from the debris to the arm. Hypervelocity impacts are difficult to predict, though, and I could be wrong here.

But again, this is all really nitpicky. And the movie got so much right. The sets were spot-on: the cramped Soyuz; the long, narrow ISS corridors; the appearance of essentially all the space hardware. I’ll note it was important to the plot that the Chinese Shenzhou re-entry vehicle was similar in design to the Soyuz, and in real life it is. When she hit the button to separate the crew module from the forward and rear modules, I practically cheered. That was accurate, and very cool.

And the scenery, well, wow. And how about this: I noticed pretty quickly that the stars were portrayed accurately! I saw the Pleiades float by, next to the horns of Taurus, and a glimpse of Orion. Other constellations came into view as well. Happily, this means Neil Tyson won’t have to confront Cuarón.

I can't leave you without mentioning this, too: Ed Harris was the voice of Mission Control. Talk about a nice touch: He played Flight Director Gene Kranz in Apollo 13. When I saw his name in the credits, my heart grew three sizes.

Dénouement

Obviously, there’s a lot to love and a lot to gnaw over in this movie. But the bottom line is clear: Go see this flick. The science errors won’t bug you, and if they do, you need to pull your head out of your assumptions of what a movie should be. As a demonstration of craftsmanship, and as a viewing experience, Gravity is astonishing. I loved it, and I’ll be going to see it again.

A final note: If this massive verbiage spewing wasn’t enough for you, lots of other people have reviewed the movie as well. I won’t vouch for how accurate their reviews are, but you may enjoy reading them.

- Dana Stevens at Slate

- Dennis Overbye at the New York Times

- Mark Hughes at Forbes

- David Edelstein at Vulture*

- Jonathan O'Callaghan at Space Answers interviews my friend Kevin Grazier, who was the science adviser for the movie. I talked to Kevin as well and basically confirmed what I said here: Some plot points were key to the movie, so the science was deemed secondary as long as it wasn’t too in your face.

- Robert Pearlman has an excellent review and interview with Alfonso Cuarón at Collect Space

Correction, Oct. 9, 2013: This post originally misspelled David Edelstein’s last name.